'Where's the entrance to the terrace?", "Where are the rest rooms?", "Where's the rattan Ferrari?".

At the 57th Venice Biennale, the world's biggest art event taking place right now, Thailand has set up shop in a restaurant, turning it into the official Thai Pavilion. This set-up puzzles some visitors, and allegorically it also tells the story of the exhibition.

Standing in the middle of the pavilion's central room, curator Numthong Sae Tang resigns himself to telling visitors asking their way that he doesn't work there. A few hours before the official opening last Saturday, the exhibition space was crowded with people who had come to see Thailand's contribution to the international contemporary art scene.

Eighty-five countries have set up their lodge at the Venice Biennale, which will run through November. But Thailand's national representation this year is dual, with the works of established artist Somboon Hormtientong shown at the Thai pavilion with the Culture Ministry's full support and a parallel exhibition by Alamak!, a private project, featuring the creations of two rising Thai talents, including the rattan Ferrari.

While Somboon's pieces display a lost, or soon-to-be-lost, vision of Bangkok, the two young stars, Anon Pairot and Kawita Vatanajyankur, accurately depict power and status relations in Thailand today.

Two charcoal sketches of Charoen Krung Road open Somboon's series of art installations and drawings, collectively titled "Krung Thep Bangkok". The busy, but still relaxed, street from a bygone era has made way for today's bustling artery, where bundles of electric cables criss-cross the facades of houses that were once neatly aligned.

"I grew up in Bangkok at a time when we still had a tramway. My house was located next to a klong," Somboon says at the opening.

The city has changed considerably since he was a child. As a young artist, he went to study and work in Germany and was stupefied by the transformations he saw when he returned to Thailand.

For his exhibition at the Biennale, the artist knew he wanted to work on Bangkok. "The city has been completely destroyed to benefit businesses. My city is unrecognisable."

The Bangkok which Somboon speaks of, with its traditional shophouses, artfully crafted wooden structures and old communities, can still be seen in small sois, located in areas spared by economic boom.

They look as if they are light years away from skyscrapers, colossal shopping malls or even the quirky, playful way the old and new sometimes mix and match in the city.

An enthusiastic city dweller, the artist recreates scenes and moments of life in the backstreets. One such installation is a fence, behind which are displayed a spirit house and some textiles. But in order to see those items, one must stick one's face close to the bars and peek inside -- just as we would do when discerning a beautiful but enclosed house.

Benefiting from the Thai pavilion's location next to the Giardini della Biennale, facing the Venetian lagoon, Somboon's take on rapid urban expansion and a general lack of consideration for past architectural wonders draws evident comparisons between the two cities.

Bangkok -- the Venice of the East -- has seen most of its canals covered to make way for roads and automobiles, whereas the Italian city capitalises on its historical glory.

While the artist delves into the past and seemingly rejects Bangkok's present state, he remains elusive regarding the future. "I don't think it will get better."

"The urban development in Bangkok is crude and superficial," Somboon adds -- the opposite of the vision he attempts to give.

However, the tools and symbols he employs in doing so -- a disparate set of Buddha and elephant statuettes, wooden furniture and coloured plastic chairs -- are somewhat conventional and outdated, betraying a rather backward-looking perspective.

Most importantly, they do not transcend their status as "objects". Although these personal items stand for the stories of their past owners -- all anonymous, but each creating another layer of history -- they seem lifeless.

Perhaps it is owing to an unfavourable site -- the Paradiso, which hosts the Thai Pavilion, is after all a restaurant, therefore difficult to convert into an exhibition space -- that the installations seem comparatively poorly displayed, failing to captivate the crowd that walks by.

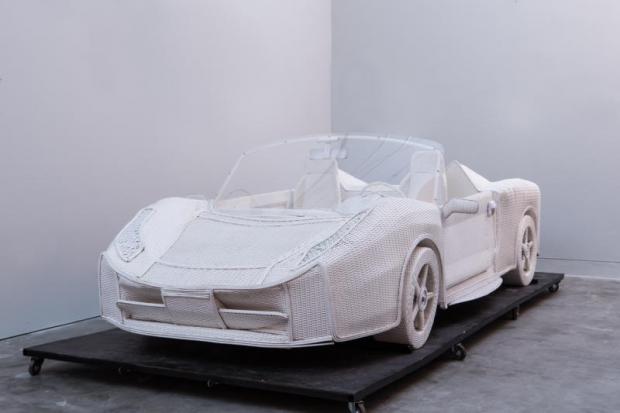

On display at the Venice Arsenale medieval dockyard -- another traditional location of the Biennale -- Anon Pairot's Chiang Rai Ferrari is the stellar opposite of Somboon's installations.

Typically, there would be nothing personal about a car, a mass produced object, even one with a design as iconic as the Italian luxury vehicle.

And yet, the white, life-sized rattan structure feels as though it is alive, animated by the spirits of those who worked to create it.

Three years ago Anon, whose main job is as a designer, was tasked by the Commerce Ministry to give advice to local farmers and craftsmen under the One Tambon One Product initiative.

These villagers have been making rattan baskets all their lives, and everyone -- from state officials to other locals -- expected them to keep doing so.

But when asked by Anon what they really wanted to make, the majority answered: "Something really expensive for once."

Luxury cars and clothing are made to look like commodity items on lakorn and television shows. "But that life seems so far from their everyday reality," he adds.

As a designer, Anon can somewhat relate to the rattan workers. "We work for the client, following instructions all day." But in the long run, the risk of it becoming a routine is real.

When one integrates social norms and boundaries, their vision becomes limited as a result, he explains. As a work of art, the Chiang Rai Ferrari was a way for both Anon and rattan workers to break free.

The art piece is exhibited alongside another of Anon's installations -- two human-sized rice bags covered in newspaper headlines and articles about the former government's controversial rice-pledging scheme.

At a previous showing in Bangkok, visitors were asked to erase the text from the bags. Laid bare, the sacks reveal to the public what they really contain: human lives.

With everyday objects, Anon parodies contemporary Thailand, where every item becomes a status symbol and ordinary people receive little consideration.

Similarly, the basis for Kawita Vatanajyankur's performance videos are often everyday situations -- which the artist then enacts in their extreme form, to highlight underlying oppression.

A sweet-faced young artist, Kawita's videos display multiple layers of her personality and artistic vision.

As we walk in Venice, she hides her face from the sunlight using her bag as a shield. But as soon as she begins talking about her performances, Kawita's voice and overall demeanour are transformed, demonstrating the boldness and confidence of her work.

Set against candy-coloured backdrops, she hangs herself on wires, carrying baskets where fruits are thrown in, or uses her mouth as an orange juicer.

Her six-minute video, during which water is continuously poured into her mouth, is cringeworthy, almost impossible to watch. "As I performed, my body began adapting little by little," she says.

The same thing goes for her Ice Shaver video, where her mouth is pressed against a large block of ice, which she rubs over a wooden stand in an uninterrupted motion. With the use of repetitive scenes, often marked with overflowing of liquids or excessive weight, the artist paints a picture of alienation through work.

Kawita uses her body in place of mechanical tools such as scales. Ironically, in many of the menial work tasks that she performs, humans will soon be replaced by machines.

After exploring domestic, typically feminine, house chores, Kawita's latest series of works tackle outdoor labour activities such as the ones she observed in a market near her home.

"It's a universal theme," she says. "Although these professions are clearly overlooked by a large part of Thai society."

Hence one of her performances is titled The Scale Of Justice, through which she attempts to re-dignify workers in the market.

Her video installations at the Venice Biennale garnered the attention of famed performance artist Marina Abramovic. As to whether Kawita herself will give live performances, the artist hesitates.

"Perhaps my performances would be unbearable to watch," she says.

The monochrome, flashy colours Kawita uses as a background soften her works, at the same time as they create contrast between rosy life outlooks and the sombre message she conveys.

Anon and Kawita's works, exhibited alongside art installations by Korean and Japanese artists, say more about Thai society than Buddha statues and elephants do.

Although anchored in the Thai socio-political context, their art reaches far beyond national borders and resonates with current issues in Asia and the world.

Human Rice by Anon Pairot. Photo: Anon Pairot

The Scale Of Justice by Kawita Vatanajyankur. Photos: Kawita Vatanajyankur

Krung Thep Bangkok by Somboon Hormtientong at the Thai pavilion. Photos courtesy of Namthong Gallery