Insein Prison, an infamous cell in Yangon, has been notoriously known for its abysmal condition. During the 1980s, the Myanmar junta used the phrase "going to Moscow" to make a threat to opponents. Political activists knew that "going to Moscow" was going to Insein prison, a trip worse than death itself. The prison fortress is known locally as the "darkest hellhole in Myanmar".

Since the military took over the country in 1962 to launch the "Burmese Way to Socialism", hundreds of thousands of political opponents, many of them students and political activists, were imprisoned at Insein. Many died from poor health, scores have been forgotten and few released. Currently, more political prisoners gradually have been pardoned and released.

Among those who walked out earlier telling the tale is Ma Thida, a renowned human rights activist, respected writer, physician, and a former aid of Aung San Suu Kyi.

A brilliant medical student and active political activist, Thida was arrested in 1993 and given a 20-year jail term. The charges against her were endangering public serenity, contacting illegal organisations and printing and distributing illegal publications. Apart from being an activist, Thida was a prolific writer and critic of the junta. Her books, articles and poems, several of which were banned, enraged the junta. Her first book The Sunflower, a political allegory published internationally in 1992, wasn't released in Myanmar until 1999. Ironically, it is only possible in a country with a totalitarian regime that the quest for freedom can be the end of freedom itself.

Ma Thida. Elite Plus Magazine

Thida reportedly described that she had looked at her prison sentence as a temporary death, and living in Insein akin to attending her own funeral.

Instead, the Insein experience became a process of death and rebirth after she decided to make the best out of her time in the notorious prison.

"Why not take advantage of being in prison to change my life and get out of the cycle to find total liberation … not physical freedom but total freedom," said Thida, now 50 years old. She looks calm, casual and ever-smiling. She had practised the Vipassana style of meditation when she was younger. Yet, her demanding schedule at medical school, her writing career and political campaign kept her away from it.

At Insein, she restarted practising Vipassana several hours a day, some days, she had marathon Vipassana sessions of 20 hours. The meditation calmed her mind and helped her cope with life in prison.

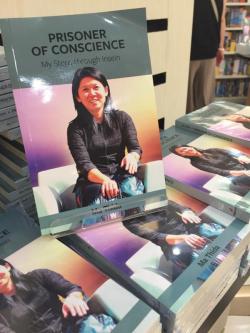

"When I was younger, I used to be aggressive, angry, arrogant. After Vipassana, I changed," Ma Thida told the media in a sideline interview during her recent speech on Asean literature at the Faculty of Arts at Chulalongkorn University. She also presided over the launch of her book Prisoner Of Conscience: My Steps Through Insein. The English-version of the book is the first released under her real name in Thailand. Her novel The Roadmap written in English under a pseudonym was released in Thailand in 2011.

Prisoner Of Conscience: My Steps Through Insein has been widely read among different groups, particularly scholars and journalists seeking to understand Myanmar politics and the tumultuous days of the 1980s. Fans of Ms Suu Kyi also have read this book as Ma Thida shared her experience working as a medic and recorder of press interviews during Ms Suu Kyi's travels to rural areas to visit poor people in the late 1980s.

"Vendors read the book. Even students read this book and the general public read it to understand how humans can cope with adversity. But many people think this book is about Vipassana meditation and that I wrote this book to promote Vipassana meditation too," she said.

Ma Thida's Prisoner Of Conscience: My Steps Through Insein book launch and signing session in Bangkok. Asia Books

Reporters often ask her about Ms Suu Kyi. Such a question is understandable. Ms Suu Kyi, known as "The Lady", is now an elusive figure, inaccessible and rarely gives press interviews.

Thida has not met with The Lady for a number of years. She is not involved with the National League for Democracy (NLD) party either. Yet, looking from distance, Thida says she feels sorry for The Lady. For while Ms Suu Kyi is the most influential leader in Myanmar and travels the world as foreign minister, The Lady herself cannot escape a different kind of prison.

"Myanmar people have too high expectations of her. It is not fair for anyone to shoulder such a burden. This is how I see her being trapped in a prison of praise, prisoner of applause."

But what about Ma Thida? Like The Lady, she has emerged into fame, as an awarded human rights activist. Indeed, she was released in 1999 due to poor health and pressure from Amnesty International and PEN International, the worldwide association of writers.

Apparently, Ma Thida is like her country Myanmar, hopeful and free, like anyone in a democratic society. She became a prominent writer, and achieved her dream of becoming a medical doctor. Over five years ago, she travelled overseas for the first time, serving as a visiting fellow at Brown University and then for advance study at Harvard University. Recently, she was elected president of PEN Myanmar.

But she has kept writing, penning books with heavy social content in order to tap people's consciences to look at land grabbing and poverty in ethnic communities. Indeed, she is not optimistic about her country's political system. While the military was sidelined, it still has seat quotas in the national security and homeland security ministries. The censorship of the old days is gone yet the Ministry of Information still decides on the content in state media and keeps private media on a leash by approving or not approving licences.

Myanmar people too are quite new to freedom. Five decades of living under military rule affected the people deeply. Myanmar people, she said, often evade criticism. "And when people evade criticism they unknowingly condone self-censorship." As head of PEN Myanmar, she is cooking up a plan to liberate people through books and words. Ma Thida plans to promote ethnic literature, which was abolished after the junta took control in 1962.

"Reading ethnic literature helps promote a deeper understanding of the attitudes and behaviours of the people."

Thida also wants to see the translation of Thai and Myanmar books. The two countries that share a long border and history, have recently lacked any meaningful cultural exchange.

"When you read about different cultures and societies through a writer's perspective, it is indeed generating the capacity of tolerance and respect on other viewpoints. After all, literature has the power to bring peace into society. So, we fight not only for freedom but also for keeping freedom in our literature too."