Pecking free of its shell, a River Lapwing chick stretches its legs. It has no idea it's hiding in plain sight. The soft hue of its feathers, a mosaic of shades mirroring the Mekong River's gravel beneath its feet, provides perfect camouflage as it readies to dutifully follow its parents mere moments after taking its first breath.

The chick is unaware that its home, where the most prized of the threatened Mekong bird species lives, is slated to disappear, and with it, hope for its breed. Worse still, scientists warn, is that ecological losses along the Mekong River are a part of the global catastrophe that Thailand and its neighbours are contributing to at humanity's peril.

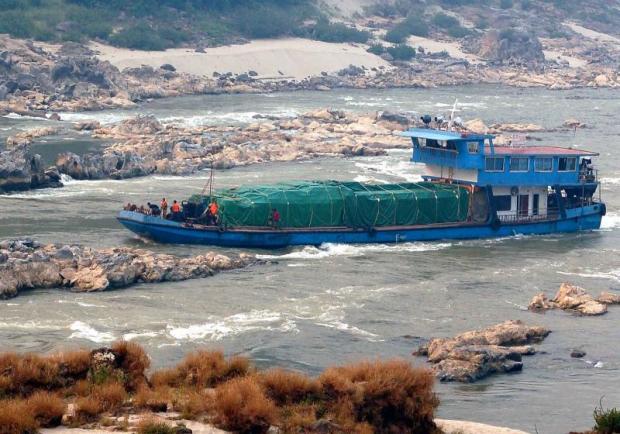

To Phil Round, Thailand's leading bird expert, plans to dynamite obstacles to create a river channel deep enough to facilitate the passage of large Chinese cargo ships is unthinkable in this era of rampant biodiversity decline.

"One way or another we're wiping out strains of a genetic code, and that section of the Mekong [River] is a treasure trove of ecological complexity that we're only beginning to understand," he says.

Starting just beyond the point where the Mekong enters Thailand from Myanmar, and extends 243 kilometres downstream, these rapids have gained international notoriety over the past 15 years due to a single fish species: the Mekong Giant Catfish.

Growing to three metres in length and weighing up to 250 kg, they are the largest freshwater fish in the world, though rarely found any more due to changes in the river flow mainly brought on by the construction of the Chinese dams upstream.

But Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok, of the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand, says attention to such "poster animals" does not scratch the surface of what is really at stake.

A Jerdon's Bushchat is spotted on a rock along the Mekong River. The largest known population of this species is found in the middle of the river around Pak Chom district, Loei. (Photos by

"The Mekong's alteration not only affects fish and the livelihoods of local people, but directly affects many species of birds all along its course," says Mr Ayuwat.

"Some are found nowhere else in Thailand, particularly the Mekong Wagtail which was not described by science until 2001," he adds.

He surmises that while some of these species may stray in search of new habitats when the rapids are gone, their long-term survival will be precarious.

"The rapids were part of their evolution, their hard wiring. Eliminating them will have severe consequences," the expert said.

Mr Ayuwat points out that the "ecological niche" accessed by different species utilising different elements of the river channel further illustrates the easily over-looked complexity of how birds come to rely on these rapids in their intact state.

For example, the Mekong Wagtail prefers rapid-forming rocks. The White-tailed Rubythroat dwells in particular grasses found on sandbars, while the River Terns make nests within the vertical banks carved by the river.

Moreover, conservation biologist Nonn Panichwong, founder of Siamensis.org, Thailand's largest online natural history museum, says that underlying the unique physical aspects of this stretch of the Mekong is a complex food web that is found nowhere else.

"The insects, the worms, the micro-organisms, many of which are hidden from view below the surface provide the nourishment these birds have come to rely on," he says. And food for the fish as well, Mr Nonn adds.

Indeed, the very presence of something as rare and large as the Giant Catfish could only have evolved from a system comprised of an assemblage of many unique organisms. For example, one of the world's smallest vertebrates, the three-spotted Dwarf Rasbora, averaging 1.3 cm, is also found within this reach of the Mekong.

A Mekong Wagtail perches on a tree on the banks of the Mekong River and its tributaries, their native habitat. photos by Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok

"And we're discovering new species all the time," says Somsak Panha, director of Chulalongkorn University's Centre of Excellence on Biodiversity.

"We've found this three-metre-long earthworm living within the Mekong's banks. Why they evolved to such a length is still unknown, but sadly they're fast disappearing due to dam-altered river flows."

To Mr Somsak, Thailand's wealth in fauna and flora represents an untapped competitive advantage in food production and health care. "Forget technology and innovation and let's focus on biodiversity research and development. Thailand is small in land cover, but our biodiversity is among the richest in the world," he says.

Mr Nonn too laments that while Thais are advancing their understanding of this natural wealth, they are ignoring the big picture surrounding what happens when it is gone.

Wire-tailed Swallows, mainly associated with river rapids, are in decline in their habitat along the Pak Moon River, a tributary of the Mekong.

"What Thailand is demonstrating with its cavalier approach toward the loss of these rapids is a smack in the face for the science that is telling us that we can no longer afford to do this -- to contribute further to the loss of species that on the whole have been critical to the planet's biological functioning and our own well-being," Mr Nonn said.

Studies like the one published last year by University College London found that for 58% of the world's land surface, which is home to 71% of the global population, the level of biodiversity loss is substantial enough to question the ability of the ecosystems to support human societies.

"Like the agreed upon CO2 emission cuts, countries are supposed to be cutting the rate of extinction, but I doubt anyone involved in making decisions about these rapids even thinks about Thailand's commitment to the United Nation's Convention on Biodiversity," Mr Nonn said.

Last week, when Transport Minister Arkhom Termpittayapaisith was presented with images of birds whose habitats would be lost by the rapids blasting, he admitted ignorance of the deeper importance of preserving the area's biological integrity.

The River Turn is becoming scarce because of the destruction of sandbanks in which it nests. Thanee Wongniwatkajorn

"Now that we know, we're not going to do anything without a thorough study of the project's environmental impacts," Mr Arkhom promised. "But at the same time we have to weigh it against the economic benefits from increasing navigation."

But therein lies the problem, Mr Nonn said. Economic valuations can't account for the true value of the species we know about, much less those yet to be discovered. "Since the human-inflected damage got into full gear with the industrial revolution, we're the first generation to truly feel the impact."

"It's fair to say that it is now our job to demand such critical habitats be evaluated differently, and to let the government know this is what it must do."

A well-camouflaged River Lapwing chick waits for food from its parents. photo from Wikipedia

A Chinese cargo ship negotiates the Mekong River where levels have dropped since dams were built in the North. Boats carrying fresh fruits and vegetables are often left stranded, prompting demands to blast river reefs, which environmentalists say will cause mass destruction of the habitats of birds and animals. Subin Khuenkaew