Aids advocacy groups have opposed a move by a company that owns the patent to a life-saving drug that will prevent its competitors from making and selling the drug in Thailand.

Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) holds the patent for Raltegravir, an expensive antiretroviral drug, which the groups say is the only option for many HIV/Aids patients as they have developed resistance to other drugs.

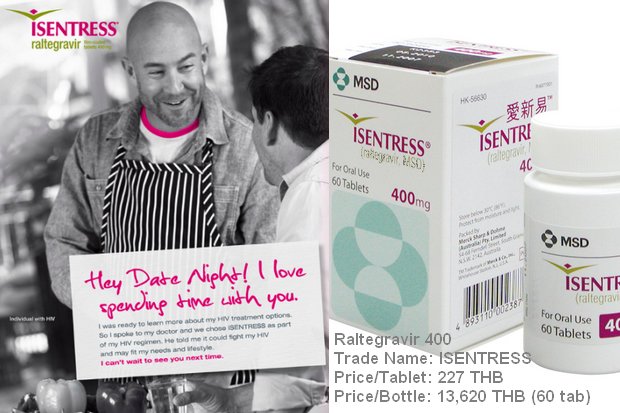

"There is the only one trademarked Raltegravir sold in Thailand and it costs 13,620 baht per month," said Apiwat Kwangkaew, president of the Thai Network of People Living with HIV/Aids.

The activists oppose the MSD's move to seek "evergreening" for the patent in Thailand. Evergreening in the pharmaceutical industry refers to a legal and business strategy by which companies with patents over drugs that are about to expire seek to retain royalties from them, by either taking out new patents, or by buying out or frustrating competitors.

The patent on Raltegravir is due to expire in 2025 but the MSD is attempting to extend the drug patent in Thailand for at least another five years, said Nimit Tian-Udom, director of the Aid Access Foundation (AAF).

The advocacy groups found the drugs company had submitted five applications for new patents on Raltegravir, which would prevent other manufacturers from making generic equivalents of the drug in Thailand.

"We're objecting to these patent applications because they are applications for evergreening for the patent on this drug which is against the 1992 Patent Act," he said. Mr Nimit said the drug had already been patented overseas and the science behind the drug had been included in pharmacology programmes at many universities.

Chalermsak Kittitrakul, a AAF coordinator, said it was a classic tactic for pharmaceutical companies to submit applications for several types of patents in overlapping periods to prolong their drug patents up to 40 years.

It was difficult to oppose such tactical applications, because the Department of Intellectual Property (DIP) doesn't normally make public such announcements, nor does it make it easy for the public to gain access to the announcements, he said. The AAF, for instance, has to closely monitor when patent applications are made available and then pay for a copy of CDs containing those announcements.

"The process of filing objections to evergreening patent applications is crucial to prevent a monopoly on drugs that don't deserve to be guarded by a patent for too long," he said.

Nanthawal Sakuntanak, acting director-general of the DIP, said he consider the AAF's objection.