It was made in the prehistoric period, an ancient bead 15cm long, tubular and consisting of black-and-white agate and orange carnelian rock. It was broken in two and buried, separately, with two bodies, perhaps relatives, in what is today the Tha Luang district of Lop Buri.

Last decade, local diggers found one section of the bead and put it up for sale on the underground market. They failed to find the other part of the bead after digging at the Tha Luang site.

But it was eventually recovered and reached the hands of bead collector Peerachai Luejaroenkiat, also vice-president of the archaeology club of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand. He thought he would never see the other part.

But last year he found a picture of a bead with a similar shape and materials posted on the Facebook page of Bunchar Pongpanich, a doctor known for being an expert on ancient beads.

PUTTING TWO AND TWO TOGETHER: Bead collector Peerachai Luejaroenkiat reunites two ancient bead parts at a collectors' event.

They met in November during a bead exhibition arranged by the collectors group Suvarnabhumi Beads.

The two parts of the bead were joined. To the delight of observers, they fitted seamlessly.

Tracing back the bead's origin, Mr Peerachai believes his was dug up by Nakhon Sawan diggers who sold it via another trade route. The two halves may have been separated for 2,000 years, even though the two graves were only 40 metres apart.

The reunion of the two halves was seen as a miracle by some bead collectors.

"If ancient beads are collected properly, they can be great indicators of the history of a location," said Dr Bunchar, who contributes beads to museums and cultural foundations. "But they are seen as minor antiques, and are not a priority in the Thai archaeological field. Very few studies look into them."

Ancient beads are forgotten Thai treasures. But in domestic and international antiques markets, the demand and value of these beads has soared.

REUNITED AGAIN: Two bead parts, made of agate and carnelian rock, were found in Lop Buri by separate individuals and reunited last year.

FORGOTTEN TREASURES

Dr Bunchar said some ancient beads found in Thailand are prehistoric.

They are found in every region of Thailand, including archaeological sites in Krabi's Khlong Thom district, Suphan Buri's U Thong district and Lop Buri. Materials vary and include glass, rock and shells.

The origins of the beads can be traced to the ancient Mediterranean, the Middle East, Europe, Africa and Asia, indicating extensive travel, trade and cultural exchange. Beads were used as ornaments for both the living and the dead and are often found in graves with other artefacts.

However, not much research has been conducted on ancient beads in Thailand.

Before the 1950s, archaeologists focused on historic periods using evidence such as written records, inscriptions, ancient remains and large antiques.

Dr Bunchar said beads were seen as inauspicious objects, or the property of ghosts. No one wanted to collect them.

The turning point came in the 1960s, recalled Dr Bunchar, when a Suphan Buri man who wore a necklace of ancient beads survived a serious accident.

News spread widely and locals started seeking out the beads as holy objects, resulting in the birth of bead hunters around the country. A network sprung up out of the trade in ancient beads.

At the same time, Thailand's prehistoric era gained more attention from archaeologists, leading to a survey of the Ban Chiang site in Udon Thani which was listed as a Unesco World Heritage site in 1992.

"But it was too late for the beads," said Dr Bunchar. "Excavation of beads went on at a level that authorities could hardly cope with."

In the past five years, social networks have taken up the bead trade which has expanded around the globe. Over 95 results can be found when searching for "khai lukpad boran" ("sell ancient beads") on Google.

Online markets have been created on Facebook, some of which require sellers to post pictures of their ID cards next to the beads to try and prevent fraud.

A single bead can range in price from as little as 1,000 baht and into the tens of thousands depending on its origin, age, materials and appearance. Ancient beads from Thailand and neighbouring countries can be found for sale on Amazon and Ebay.

Necklaces made of ancient beads can be seen on the necks of local politicians and influential people in Thailand as they are believed to attract luck and prestige.

Bead collectors told Spectrum that foreign collectors have dubbed Thailand a paradise for the trade. Chinese buyers have emerged as major players in the last three years.

PRESERVING HISTORY

The Act on Ancient Monuments, Objects of Art, Antiques and National Museums requires people who discover ancient beads to deliver them to the Fine Art Department as they are considered state property.

The law allows the trade of antiques within Thailand and important artefacts owned by individuals must be registered with the FAD. Owners of artefacts must also notify authorities when an item changes hands.

But beads are not considered important pieces, according to department officials.

In response, some bead conservationists have tried to encourage authorities to implement systematic registration for beads.

Most ancient beads belong to individuals and some are with museums. Without proper analysis and documentation, it is hard to estimate their availability. There are few official reports about beads, but these barely begin to cover the vast scale of collecting in Thailand.

Even though beads are prevalent in some markets, new pieces are still being discovered and delivered to buyers. Meanwhile, authorities are doing little on regulation.

"Personally, I think not all beads but only important pieces should be registered with the government so we know where they are," said Dr Bunchar.

Some bead collectors have positioned themselves as potential conservationists. While there are collectors who sell and resell beads, some have committed to not reselling beads as a means of preserving them.

Mr Peerachai, well known for his collection of beads from Lop Buri, has gathered the artefacts for more than 10 years, fuelled by both passion and a curiosity about history. He often posts images of beads from his collection on Facebook, while sharing anecdotes about his finds, always insisting he will not sell his collection.

"I was enticed by a question about where Thais are from," he said. "The prehistoric period seems blanketed by inadequate study. Beads can fill missing gaps."

A controversial theory that "ancient Thais migrated from the Altai Mountains [in Central Asia]" was introduced in 1928 and taught in Thai schools.

Due to questions over the evidence, the Ministry of Education pulled the above phrase from textbooks in 1978. But the theory has taken root in Thai society.

The theory continues to be shared in classrooms and publications, challenging nationalist beliefs that Thailand was founded by pure, ancient Thais.

Recent evidence presents a different theory that some Thais are mixed race. Mr Peerachai and some bead collectors were convinced of this theory by beads, which they say show a clear mix of cultures.

However, he acknowledged that acquiring these pieces of ancient history often involves buying beads from shady diggers.

"As collectors, this is our sin because we buy beads from people who dig them up. But from another angle, if we don't buy them, others will. Perhaps foreigners," he said.

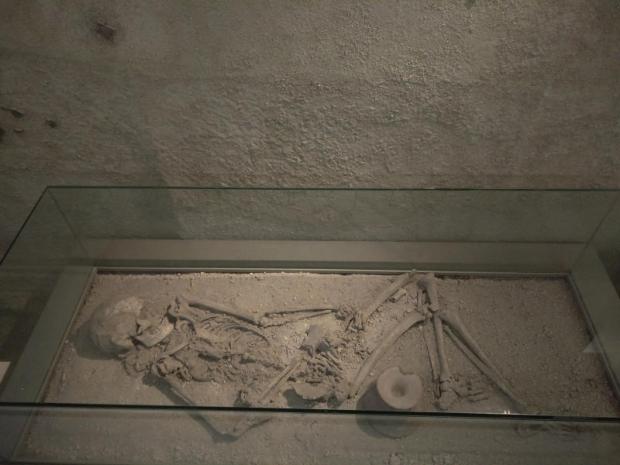

BEAUTY IS BEAD DEEP: Ancient beads displayed at King Narai National Museum, Lop Buri. Beads can be not only beautiful but historically telling.

DARK SIDE OF COLLECTING

As demand for beads has grown among collectors, illegal excavation has continued.

Thawatchai Chanpaisalsilp, an archaeological specialist at the Fine Art Office in Phuket, received a report of holes and excavation tools abandoned in Khlong Thom a couple of months ago. No diggers were found.

He believes that demand for beads has increased, especially after the emergence of online markets. However, technology can also be a useful tool for authorities to track antiques.

In 2013, officials were able to track an ancient cannon that had disappeared from a Ranong archaeological site. Officials were able to track it down after smugglers posed for pictures with the cannon that were posted on Facebook.

Local archaeological watchdogs are also an effective way to assist with the monitoring of archaeological objects.

At Ban Klang village in Krabi's Ao Luek district, locals formed a watchdog group in 2014 to monitor over 10 rocky hills near their homes that contained prehistoric archaeological objects such as beads, tools and rock paintings, with some artefacts dating back 3,000-5,000 years.

Initially, the group came together to protest against the stone milling concessions that had been granted for the hills. The group later expanded its mission to include archeological protection.

"We didn't know at first that our home had valuable archeological artefacts," said Kriangkrai Kwanduean, 31, a member of the group.

For years, they have seen abandoned holes, some as deep as two metres, along with tools and human bones scattered around the area.

The frequency of new holes has declined since the watchdog group formed. In April, they found a new hole and sieves, indicating the ongoing excavation for ancient beads.

Krabi remains one of the most famous places to find ancient beads. Collectors have been drawn to the area since the discovery of the rare Sun God glass-bead, one centimetre in diameter with a face in the middle surrounded by red and green stripes that simulate the sun's rays.

Lop Buri has also become a popular destination for bead hunters, prompting academics to urge authorities to conduct comprehensive studies of beads in the area before it's too late.

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

At the edge of Chatuchak market, there's a section specialising in second-hand goods that is crowded with visitors every weekend.

Amulets, shoes, books and leather goods lie along the sidewalk. Among them is a shop with beads in a glass case which belongs to Daranee Rassameesiri, a 41-year-old bead collector.

Not all beads in her case are for sale, many are just there for display.

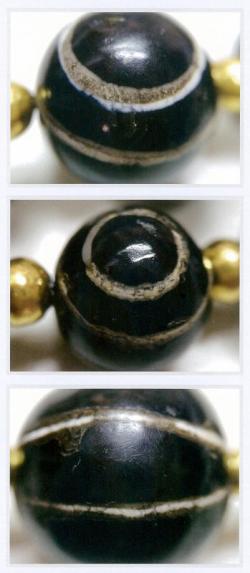

On her necklace shines a "Cat Eye" bead, spherical in shape, made of black rock with white stripes. The market value for the bead is 80,000 baht, but she would never sell it. It's a part of her spirit.

"Beads are profound. I can hardy explain," she said.

After working with beads for 20 years, she is now a core member of Suvarnabhumi Beads, a group of bead collectors with over 3,000 mostly Thai members. Other members are Afghan, Myanmar, Cambodian, Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Taiwanese and Vietnamese.

They connected through Facebook, posting photos of beads and sharing the history of each piece.

Ms Daranee's shop has become an unofficial meeting place for bead collectors.

Ms Daranee helped the group arrange a one-day gathering of bead collectors last November, the same event where bead fragments owned by Mr Peerachai and Dr Bunchar were reunited.

Over 600 people from various countries attended the event. Around 100 were Chinese. Participants paid homage to the beads' ancient owners to ask for forgiveness. The event was divided into a section for exhibitions and knowledge sharing and another for sales.

Some participants estimated that money exchanged at the event included figures of five and six digits.

Ms Daranee believes that if bead collectors come together, they can protect many important pieces, and use them to bring value to Thai archaeology and tourism.

In past years, some foreign bead collectors have arranged tour groups to observe beads in Thai museums. Knowledge about the history of beads continues to be exchanged on digital platforms.

Smuggling beads is certainly controversial, but some collectors view this as necessary to restoring and conserving beads.

Beads are now traversing the globe, much like they did thousands of years ago.

In Ms Daranee's case, her collection may end its journey at museums when she perishes. Some collectors say beads pick their owner, hopefully one that agrees to preserve their history. n

CLOSE TO THE BONE: Prehistoric human remains in King Narai National Museum, dating back 1,000 to 3,500 years, have been found with ancient beads. Paritta Wangkiat

Look closely: Bunchar Pongpanich holds a picture of the rare God Sun bead. PHOTO: APICHART JINAKUL

PRECIOUS PENDANT: Agate beads from Dr Bunchar's book 'Beads of Lop Buri'.