For the past 39 years, Anutas Pleeta's family have made a living out of growing para rubber on their four-rai plantation in the southern province of Phangnga. By this time of the year, the trees would have been ready for tapping and Mr Anutas would have had more money to support his family of five, who currently live off an average income of 45,000 baht per year -- less than half the daily minimum wage -- from rubber grown on another six rai of land.

In June 2014, he was accused of encroachment and forestry officials from Si Phang Nga National Park ordered him to cut down all his crops. He had 30 days to do so, according to the piece of paper attached to a stake that was placed in the middle of his plantation, or else authorities would demand payment for doing the task themselves.

Mr Anutas doesn't have any title deeds but his father has lived off the land since 1962. When Si Phang Nga was declared a national park in 1988, no announcements were made locally.

After the coup in May 2014, authorities took action against Mr Anutas following an order that instructed the military and the Internal Security Operations Command to help reclaim forest land and suppress encroachers.

A subsequent order by the junta-led National Council for Peace and Order had a clause stating that authorities' actions must not affect the poor and those with no access to land.

But attempts by Mr Anutas to fight the move failed when Si Phang Nga claimed his income was not of the subsistence level of 30,000 baht per year, according to a letter it submitted to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand in June this year in response to a complaint filed by Mr Anutas.

At the end of last month, two of Mr Anutas' neighbours had their crops destroyed by forestry officials.

"[One of my neighbours] came to my house and cried after her crops were destroyed. I used to tell her to fight, but she's afraid of being sent to prison. This is the fate of the poor who don't have the means to fight," he said.

Mr Anutas would have faced the same fate that day if he hadn't petitioned the governor less than a week earlier, resulting in a decision to postpone the cutting down of his crops.

This is the third time authorities have threatened to destroy Mr Anutas' crops, and he is not alone. As of today, the NHRC has received nearly 100 complaints by people who have been affected by the NCPO's crackdown on forest encroachment since 2014, up from only 12 complaints filed between 2007 and 2013.

The NHRC says forest encroachment cases represent the largest segment of complaints in that period, mainly by poor villagers, despite the NCPO order to limit the scope of reclamation operations to wealthy business operators.

UNDER PRESSURE

The complaints seen by Spectrum detail instances of government authorities issuing threats, destroying property and prosecuting poor villagers, most of whom lived there before the areas were designated as forest reserves.

In August last year, the NHRC compiled a 40-page report detailing 42 cases of complaints arising from the two NCPO orders, which were described as creating "significant loss, conflict and stress towards people".

LEGAL ADVICE: Sayamol Kaiyoorawong says the poor have no choice but to encroach on forests. Photo: SUPPILED

The report, which essentially called the government's actions a violation of human rights, was presented to the cabinet a month later. Among the NHRC's suggestions was for the cabinet to revoke the government's new master plan to increase forest cover to 40% before 2027. The plan was approved by the NCPO in August 2014, with Isoc tasked to coordinate with other governmental organisations.

The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment issued a response to the NHRC report in January this year, basically saying that authorities acted according to the law and that all related agencies were informed of the land reclamation process.

The NCPO orders have put pressure on authorities, who risk violating the law for dereliction of duty if they fail to take action against encroachers.

Phu Pha Man National Park chief Sombat Suphasorn was under scrutiny after a group of villagers filed a complaint to the Office of the Ombudsman in May last year. "It's not that I want to [take action], but the policy is pressuring me every single day," he told villagers in Phetchabun's Nam Nao district last month.

The complaint followed attempts by the park to force several people off their land used for farming in Loei province. Maliwan Pengkamma, 47, was told to remove her wooden hut near her 25-rai plantation, but she refused to do so, saying she couldn't afford the demolition.

For three months, villagers weren't allowed to harvest their crops, said Mrs Maliwan, adding that her family had owned the land way before the area was announced as a national park in 1991.

Mediation attempts by the Office of the Ombudsman resulted in Phu Pha Man allowing all the villagers to continue using the land under the NCPO order that spares poor villagers.

In March, forestry officials conducted a land survey to make sure there was no further encroachment. But villagers claimed the survey did not include about 100 rai of the 410 rai they owned. Mrs Maliwan claimed she lost three or four rai of her own plantation.

"If I had planted some crops in the area that was left out [of the survey], I would have been accused of encroachment," she said. "At least I can sleep now. In the past, when I closed my eyes, all I could see were images of forestry rangers in their camouflage uniforms."

HOW POOR IS TOO POOR?

The 21 villagers who were allowed to continue using the land were allowed to do so because they were considered poor, said Mr Sombat, although he admitted there were no clear guidelines to identify poverty.

lead-in: Caption. Photos: SUPPILED

"Basically we asked them to verify themselves, but if we later find out that they aren't poor, we will have to take action against them," he said.

But the master plan also makes a priority of cracking down on those who exploit forest resources for business or profit, said Royal Forest Department director-general Chonlatid Suraswadi, adding that his department has identified 970 resorts and hotels that have encroached on forest reserves.

"Every [poor person] who has lived off the land before 2014 is reaping benefits [from the order]," said Mr Chonlatid.

The MNRE has prosecuted 2,288 people in 11,957 cases of forest encroachment covering 269,472 rai since the 2015 fiscal year starting October 2014, roughly four months after the NCPO order on the suppression of forest encroachers came into effect.

In another major case, Sai Thong National Park is targeting 923 encroachers living on 13,974 rai, according to a letter signed by the Chaiyaphum governor in August. Of the total, 12 villagers have already been charged.

In an internal Isoc document seen by Spectrum, Isoc acknowledged the large amount of complaints stemming from "double standards" of government officials taking action against the poor rather than the rich. It instructed its officers to be lenient on the poor to prevent "anti-government sentiments from spreading".

The document, dated October last year, listed guidelines for identifying poverty levels. Those with low income, for instance, should not own more than 25 rai of land or several plots of land.

But the guidelines have not been strictly enforced, with Isoc later explaining to the NHRC that the guidelines were only circulated internally.

In a meeting with Deputy Prime Minister Prawit Wongsuwon on Aug 26, the NHRC submitted a letter urging the government to set up specific guidelines to identify the poor and to call off all actions that might affect the poor.

"Although the NCPO has made it clear that any procedure must not affect the poor who have lived off the land prior to the NCPO order being issued … the NHRC has found that government agencies have in fact seized land, demolished houses and cut down crops belonging to the poor," said the letter seen by Spectrum.

While Mr Chonlatid admitted that law enforcement will increase efforts under the current government, he said other measures are also being implemented, such as promoting the plantation of sustainable crops and reforestation.

AGEING SCHEME

Since the NCPO staged the coup in May 2014, tackling forest encroachment has been high on its agenda. By August that year, the MNRE was charged with drawing up a 10-year master plan for forest management, with the goal of increasing forest cover to 40% of the country. According to the plan, forests covered 53% of the country or 171 million rai in 1961, but that had shrunk to just 31.5% or 102 million rai in 2014.

This had occurred mostly because forests had been turned into agricultural area, said Mr Chonlatid.

The Forest Department didn't say how much forest land will be reclaimed from encroachment, saying figures will be announced this month. However, government data in 2010 shows almost 800,000 families (experts say the figure could reach one million) living on state land, including reserved forests, national parks and land owned by the Treasury Department, which would mean millions of people would be displaced if action was taken against them.

The Forest Department expects that by next year Thailand's forest reserves will increase from the current 72 million rai to 81 million rai or 25% of the country's total land mass. The remaining 15% or 48 million rai is to be allocated for farm forestry, which Mr Chonlatid says is the solution for increasing forest land in a sustainable manner.

"The trend is to focus on turning wood into products as many agricultural crops don't fetch good prices," he said.

Thailand has few commercial tree plantations, with most logging in natural forests conducted by the Forest Industry Organization, a state enterprise under the MNRE.

One of the reasons why forest reclamation has been so slow, said Mr Chonlatid, is due to the difficulties that state officials face in creating understanding among communities.

"There hasn't been much progress [in achieving the 40% goal] in the past, but now we're starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel," he said. "Some Thais have misunderstood that it's their right [to live on forest reserves], which is why the NCPO orders are necessary to force them out."

Adding to the complexities is a 1998 cabinet resolution saying that locals living in forests prior to that date could continue to do so. The department uses satellite images taken in 2002 to verify whether locals were living on forest land before or after the 1998 resolution.

But many villagers have refused to make land use claims under this method, saying images used to prove land encroachment were inaccurate and that the verifications lacked villagers' land occupation histories.

According to the resolution, those who moved in after 1998, and residents of areas at environmental risk, were to be evicted or relocated. People were allowed to remain living in the forests on a temporary basis pending verification.

NEED FOR OVERHAUL

Even though the NCPO has said the crackdown will not be directed at poor people, the order does not exempt those who faced lawsuits prior to the order.

SEEKING JUSTICE: Anutas Pleeta holds a sign stating he has been ordered to destroy his crops. Right, a notice on his para rubber plantation orders him to cut down his crops within a month. Photos: SUPPILED

Forest encroachment is a criminal offence in Thailand, with violators facing a jail term of up to seven years and/or a fine of up to 100,000 baht.

While activists support participatory forest management as the most effective way to safeguard forests, the law itself doesn't allow the coexistence of people in forest areas. The government says it promotes public participation by allowing communities to set up community forests with the Forestry Department, with 9,832 community forests currently covering 4.65 million rai.

But the regulation does not allow residential use of land or include forest areas located in national parks.

"Thailand's forest law only has the suppression aspect," said Sayamol Kaiyoorawong, deputy secretary of the Law Reform Commission of Thailand, who is advocating the use of forest land for residential purposes among low-income people. "But the poor have no choice but to encroach [on forest areas]."

Ms Sayamol said high-ranking government officials are reluctant to amend the law or adopt an inclusive forest conservation policy because doing so would mean less room for corruption. Under the existing law, government officials have absolute authority, she said.

Kritsada Boonchai, an NHRC forest and land rights subcommittee member, said the conflict regarding forest encroachment has its root cause from the government failing to accept that communities have the right to live off the land even before the enactment of the forest law.

Community rights are stipulated under Thailand's new constitution, stating that people have the right to manage, maintain and utilise natural resources in a sustainable manner according to the law.

"But the country's forest laws violate community rights, and so do the NCPO orders," said Mr Kritsada. "Despite saying that authorities' actions must not affect the poor, the orders do not accept that communities have the ability to manage resources in a sustainable manner."

The plan to increase the percentage of forest land to at least 40% of the country has been on every government agenda for the past 30 years, and the goal is included in all national economic and social development plans. Experts say the figure was first proposed by the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization, although it was not backed by any concrete study.

Many academics in the forestry field consider the goal to be outdated, with Mr Kritsada arguing that the country does not need to go any further than the current figure of 33%. Increasing forest land to 40% would require an additional 26 million rai of land, which would be an uphill task.

"The question is, where will that 26 million rai come from?" he asked. "The poor have the right to access resources for survival, but the government doesn't understand that its primary duty is to protect the rights of its citizens."

DISPUTE: Maliwan Pengkamma accompanies forestry officials on a new survey of her land. Right, Sombat Suphasorn, far right, was under fire last year for prohibiting villagers from harvesting crops.

HIGH TECHNOLOGY: A GPS device is used to survey each plot of land. Phu Pha Man National Park conducted an initial survey this year but was criticised for excluding 100 rai.

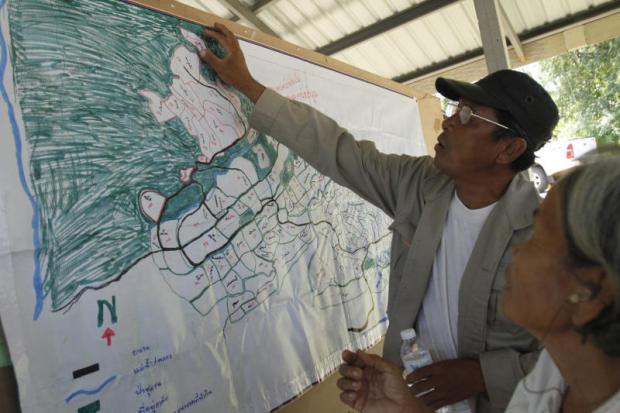

FIGHTING BACK: Villagers attend a briefing with a representative from the Office of the Ombudsman last month. Below, villagers look at a map of their farming land after being accused of encroachment.

Photos: Pornprom Satrabhaya

HOT SEAT: Phu Pha Man National Park chief Sombat Suphasorn says he is under pressure to take action against encroachment.

STANDING FIRM: Chonlatid Suraswadi says the law will be enforced but other measures are being implemented to tackle encroachment. Photo: SUPPLIED

CHECKING DOCUMENTS: Forest officials have been told to reclaim encroached land under an order from the junta-led National Council for Peace and Order. Photos: Pornprom Satrabhaya

STANDING FIRM: Chonlatid Suraswadi says the law will be enforced but other measures are being implemented to tackle encroachment. Photo: SUPPLIED

IT'S GOOD TO TALK: Villagers have a discussion with Lt Col Theppajit Vinagupta, in the blue shirt, an investigating officer at the Office of the Ombudsman.

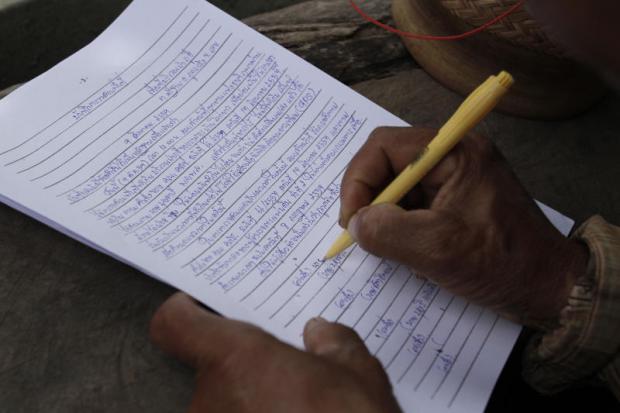

MAKING AN IMPRESSION: An officer from Phu Pha Man National Park assists a villager to print his thumb instead of his signature. Photos: Pornprom Satrabhaya

FORMALITIES: An officer drafts an agreement with 21 villagers to allow a land survey. Left, a villager gives a thumb print.

SUPPORT: Kritsada Boonchai of the National Human Rights Commission is helping villagers. Photo: SUPPLIED