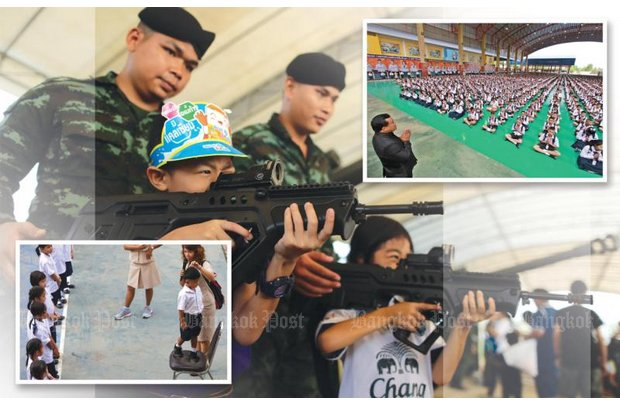

Is Thailand inching toward being a military state? We might get some clues from the photos of primary school children performing military drills that recently went viral on social media.

The photos show a group of soldiers towering like commanders over rows of pupils aged eight or nine sitting submissively on the floor. It was part of the school's disciplinary programme seen widely as an effort to indoctrinate them into total submission to military rule.

What hope do we have for democracy when schools become the biggest cheerleaders of the military?

Sanitsuda Ekachai is former editorial pages editor, Bangkok Post.

True, for the past three years the junta has relentlessly been using threats and detention to silence criticisms against military rule and its Big Brother policy. Public discussions on state-sponsored projects with serious social and environmental costs are banned. Even calling the junta a dictatorship risks arrest.

The sticks work. Yet the powers-that-be know the most effective way to suppress dissent lies in the indoctrination of children. Schools then become the junta's next front to deepen its power.

The controversial photos showing primary school pupils in Prathom 3 and 4 doing military training first appeared on the website of Srinakharinwirot University Prasarnmit Demonstration School. The pictures were immediately taken down in the wake of fierce criticism from parents and netizens.

Informally called Satit Prasarnmit, this elite Bangkok school -- like other "Satit" or demonstration schools run by universities -- has long been known for its relatively liberal philosophy on education that values self-expression in contrast to the focus on total obedience to authority in mainstream public schools. That it is now using military drills to teach discipline reflects a deepening militarism in Thailand after the 2014 coup.

The outcry from parents and netizens, while reflecting simmering discontent against increasing military intervention in daily life, is ignored by school authorities.

In her recent interview with the media, associate professor Prapansiri Susaoraj, dean of the Education Faculty at Srinakharinwirot University, said she did not understand what all the fuss was about. She insisted other prestigious schools in the capital are doing the same thing, then blamed parents for weak parenting. Since the root of the problem is children's lack of discipline, what better trainer could there be than the military, she asked.

Once they have been well-trained, the kids will know how to walk smartly, queue for lunch in an orderly fashion, and look dignified during the morning flag-hoisting ceremony, she said.

Do you know of any country using soldiers to train children how to queue up?

I have always believed the core of discipline is respect or consideration for others, both in public and private. Am I wrong?

The dean is right about one thing, which makes the situation more worrying. Hers is not the only school using soldiers to teach iron discipline. Military drills in schools are more widespread than you may think. The pupils at a school run by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) near my house are also subject to military drills once a week. Kindergartners are not exempted. Certainly, this BMA school is not the only one doing this.

Can parents protest? The parents at BMA-run schools are mostly informal workers or from the lower-middle-class. Under our hierarchical social system, they naturally feel intimidated by school authorities. It's not much different at the Satit schools for the wealthy. Since school authorities have a say over the limited seats available for students, parents feel obliged to keep their discontent to themselves.

Discuss any problem in Thailand, from economic disparity to political instability or a lack of global competitiveness, and fingers will quickly be pointed at the outdated, centralised education system. And rightly so.

Class hours in Thailand are among the highest in the world. So is the education budget in proportion to the country's total annual national budget. Yet Thai students' scores in international tests are consistently among the world's worst.

The school system's championing of ultra-nationalism based on the false belief of a pure Thai race also produces deep discrimination against ethnic minorities -- a big mental obstacle to peace amid violent ethnic conflicts.

Its focus on "tradition", meaning a strict observation of the power hierarchy and patriarchal values, explains why a child's questioning mind is treated as a challenge to power and one that must be punished. It also explains why gender inequality has become institutionalised, and why schools embrace militarism without question.

Despite calls for reform, the Education Ministry retains its central control, perpetuating the authoritarian school culture, the system of rote learning, and focus on examination scores (which favours the rich, who can afford expensive tutoring). The result is an ever-widening education gap between rich and poor and continuing indoctrination of cultural values that perpetuate inequality.

How to escape this oppressive education system?

The wealthy can send their kids to international schools or those located overseas. To add some local choices into the equation, a group of educators have set up a few alternative schools to offer holistic and humanistic education. High tuition fees, however, put these out of reach for most people.

Homeschooling is subject to strict regulation by the Education Ministry. It also requires full parental participation, meaning it is available mostly to families with little work pressure or financial concerns.

In short, the choices are expensive and available only to those who can afford them.

But people in rural communities also want better education for their children. They believe this would be possible if the Education Ministry were to allow them to manage small schools in their vicinity, as well as design their own curriculum to answer the needs of students, communities and job markets.

At present, local schools cannot even hire their own teachers. The standard curriculum is designed in Bangkok. And the Education Ministry determines who to hire as teachers, where they teach, and how they are evaluated.

Local communities want to have a say. They want the teachers to be accountable to the communities, not the bureaucracy in Bangkok. But they always hear the same answer from the Education Ministry: "No."

Worse still, the ministry wants to demolish small schools, saying they are not financially viable.

The Satit Prasarnmit does not fall under the Education Ministry, yet it has fallen under the same spell of mainstream education ideology that does not question militarism. Will a decentralised education system make any difference? I believe it will.

True, the authoritarian school culture and military-like discipline will not disappear easily, but allowing communities and parents to participate in school management will create a more open environment that will gradually erode the hierarchical, top-down authority.

Even when the powers-that-be want to assert their power, communities will find a way to strike a compromise in favour of a more dynamic education to better serve their children's future.

Children have different needs. Only through a decentralised education system with community support will schools be able to develop different options to answer children's diverse needs.

Decentralisation allows communities and students to speak up and take charge. When they do, there is no looking back.

But if the current education system and authoritarian school culture remain intact, who would be surprised to see Thailand become a military state under the ruling junta one day?