The rejection of the draft constitution has caused a major brouhaha among political pundits, academics, and journalists. But for the normal folk outside the capital, it is just another episode of lakhon nam nao, a brainless soap opera.

People at the grassroots don't find this particular lakhon fun to watch. They can't identify with anything in the script and the story line has failed to arouse their imagination or hold their attention.

No need to wonder why, for they had nothing to do with the drafting of the so-called highest law of the land and the draft itself has nothing to do with them though the drafters claimed to have them in mind when they were working on it.

The exercise from the start has focused on tinkering with the structure of state power to determine who will control the state's machinations after an election. The welfare of the electorate, especially those in the lower rungs of society, if it was thought of at all, was almost forgotten.

The people in the countryside have more mundane and immediate worries on their minds than to be concerned about how many people should be in the House or who should make up the Senate.

They are worried that nothing will grow on their land, parched by the most severe drought in living memory.

They are worried that someone has produced a land document they never knew existed to make a claim for their land.

They are worried about the state's accusation of encroachment on public property and losing the land on which they have worked for generations.

They are worried that mining and petroleum exploration and extraction is putting their land, their lives, their livelihoods and the environment on which they depend at risk.

They are worried that the prices for their produce have hit the floor while those of other essential goods keep rising.

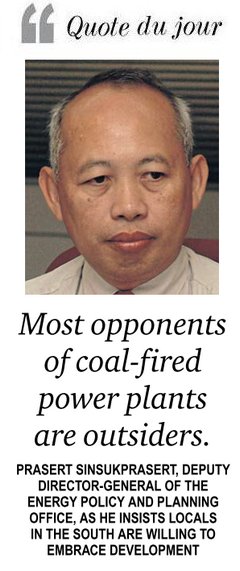

A villager holds up an anti-coal flag after protesting against government plans to build coal-fired power plants in Krabi. Local communities are concerned about megaprojects that hurt the environment and their livelihoods, not the charter-drafting game. Patipat Janthong

They are worried that massive development projects will disrupt their lives, threaten their health, destroy their livelihoods and poison their environment.

And for all the worries of the people in the countryside, their voices are not being heard in the corridors of power. Not that they haven't tried to raise their voices. It's just that every time they tried, the force of state power, backed up by military might, would clamp down on them.

They feel as if their rights as citizens have been stripped away and they have become aliens in their own country.

The military regime may have told the nation that it has been working hard to boost the economy and improve citizens' lives and welfare.

It has, for instance, brought down the price of lottery tickets, cleaned up public beaches, cracked down on resorts encroaching on state land, sent some crooked and corrupt officials to possible trial and worked on the protracted problems of illegal fishing.

But hidden behind these glowing achievements are policies that favour major industries at the expense of people on the ground and the environment.

Mining companies have been assured of licences to mine for petroleum and ores, particularly gold, covering vast areas of land, including pristine forests. In the meantime, villagers around mining sites have been left to battle health problems stemming from poisons used in mining operations while the state shows little concern.

Plans for industrial estates, special economic zones, power plants, deep-sea ports, etc have been initiated that strike fear into the hearts of people in targeted areas.

The processes to keep these plans moving have often been shrouded in secrecy. Details about them have been hard to find while people questioning the projects have been prevented from participation, oftentimes by the strong arm of the military.

Chainarong Sretthachau, a lecturer on community development at Mahasarakham University, is not optimistic about the future direction of politics.

Having worked closely with grassroots movements for much of his working life, the lecturer said people at the lower levels of society have been hit particularly hard by military rule. The regime's unabashed willingness to align with big business means the people have lost whatever leverage they might have.

He believes that the industrial-bureaucratic complex will exploit military rule to rush through harmful projects, which had been kept at bay in the past by public opposition. The longer the military is in power, the more time the projects have to launch and the more people will suffer.

A prolonged military stay does not bode well for the stability of the country despite the regime's vow to the contrary.

Frustration at the grassroots level has been brewing while the military puts a tight lid on it. In time, it will boil over, giving the people courage to stand up against military rule, a development we have seen a few times in the past.

"History tells us that violence will break out before the military steps down," Mr Chainarong said.

"Nobody wants to see that happen. But if the military refuses to learn from past coup regimes, it would be hard to avoid [violence]."

Wasant Techawongtham is former News Editor, Bangkok Post.