Thailand's relations with the outside world were naturally complicated by its latest military coup in May 2014.

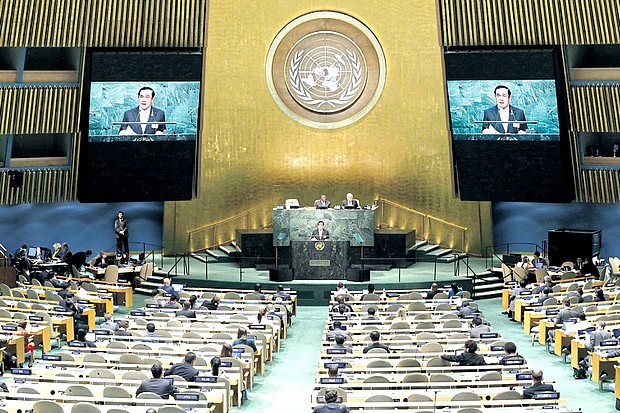

Led by the United States, Western democracies and a few democratic Asian countries opposed the putsch while most of the rest of Asia and the broader international community took it in their stride. After 16 months, in view of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha's international reception during his visit to address the annual United Nations General Assembly in New York this past week, relations between Thailand and the outside world have been recalibrated for expedient reasons.

For Thailand, this translates into less outright pressure from outside against the military regime. For Western democracies, ceding some space regains corresponding leverage with more nuances to work with. The role of Asian countries in pushing for Thailand's democratic return will now become even less significant, Japan's included.

Always the most consequential from the outset, domestic pressure now holds the key to Thailand's eventual return to popular rule. It is instructive to survey the hitherto phase of international dealings with the post-coup Thai government. The tough US posture towards Thailand's putsch in 2014 was attributable to Washington's perception of the Thai military's deception. In April 2014, just days before the coup, both Deputy Assistant Secretaries of the Defence and State Departments reassured a think-tank audience in Washington that a coup in Bangkok was not in the offing. They were told so. So were their uppermost diplomats at the US embassy in Bangkok.

Unlike the Thai military's prequel takeover in September 2006, its follow-up eight years later met stiff opposition in Washington, accompanied by measured sanctions, downgraded relations, and repeated calls for the immediate restoration of elections and democracy. Washington may have felt that it was taken for a ride in 2014 while it had been relatively lenient with the Thai military's preceding coup.

Having exercised its leverage all at once with post-coup overreactions, Washington may now be in for a relatively greater give-and-take mode as long as the junta's roadmap remains on track. Indications of this new phase of a more nuanced position can be gleaned from the early manoeuvres and preferences of the new American envoy in Bangkok. China, on the other hand, was going to be a fair-weather friend irrespective of Washington's severity of response. Beijing was nonchalant in its reaction to the related putsches in 2006 and 2014. But because Washington's hardline reaction in 2014 was so conspicuous, Beijing's embrace of the coup-makers became that much more salient. As the chorus of Western criticism against the junta gathered sound and fury, Thailand's top brass sought and received succour from Beijing.

The contrast between Washington's opprobrium and Beijing's acceptance vis-à-vis the May 2014 coup has characterised Thailand's post-coup relations with the outside world.

The key voice in Asian reactions toward the Thai putsch was Japan. With the US spearheading the Western pack, comprising the European Union in parts and as a whole, along with Australia and New Zealand in opposing the putsch, Tokyo accounted for much as a staunch democracy that is Asian. The Japanese were caught between a rock and a hard place.

Japan did not want to "lose" Thailand to China, as it felt it had lost Myanmar in that fashion in the mid-1990s, but it had no choice initially than to condemn the coup and call for the restoration of democratic rule. By September 2014, senior Japanese diplomats were in search of a more nuanced position. They even wanted Prime Minister Prayut to visit his counterpart Shinzo Abe in Tokyo in response to an earlier flurry of high-level visits between senior Thai and Chinese government and military leaders.

To their credit, the Japanese got their cake and ate it, too. Mr Abe received Gen Prayut in Tokyo, signed a memorandum of understanding to build an east-west rail project in Thailand, and enticed the Thai leader to publicly reassure an election date of early 2016. Never mind that this election pledge subsequently slipped to mid-2017. Japan made its point. It opposed the coup on democratic values but found a way to protect its interests vis-à-vis China in mainland Southeast Asia.

The turning point for Thai leaders to branch out and seek hedging strategies from Japan was Beijing's proposed rail development financing terms that came with a relatively high interest rate and short grace and repayment periods compared to World Bank and Japanese development financing standards. When it came time to capitalise, the Chinese terms were tough, leveraged by diplomatic advantages over Bangkok.

Tokyo saw it even the game vis-à-vis Beijing in the post-coup Thai sphere. With the Abe government's security bills that reinterpret the pacifist constitution to enable Japan's military to operate abroad more elastically, Thailand will have more leverage vis-à-vis China. Japan's upping its game against China in the Thai coup context is arguably the most important contour of Asia's post-coup Thailand conundrum.

Other Asian democratic concerns were ephemeral. Both President Benigno Aquino III of the Philippines and then-President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono of Indonesia expressed disapproval of the Thai coup within hours almost by instinct but these were not sustained and later succumbed to Asean's cardinal non-interference expediency. India and South Korea, the largest democracy worldwide and a consolidated East Asian democracy respectively, stood out for their relative indifference and routine business-as-usual approaches. For them, interests trumped values.

The same can be said of Thailand's other Asean neighbours, none known as bastions of democratic rule. They can hardly be blamed in view of an incipient Western retreat from democracy championing of late.

In May 2015, for example, Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop became the first senior leader of a Western country to visit Thailand and effectively recognised the Thai junta. That governments critical of the coup are apparently softening their stances in favour of nuances and room to manoeuvre is unsurprising. Thailand just has too much critical mass in the geopolitical mix and geo-economic stakes to be shunned.

Prime Minister Prayut's presence at the UN was tantamount to a fait accompli. His military government that seized power by force is intent on hunkering down until mid-2017, when an election is supposed to take place. No country can do much about it. Having successfully withstood international pressure, the danger for Gen Prayut now is the trappings of power. Once he is entrenched in office, he will find it hard to leave for one reason or another. And military regimes have not ended well around here in the last four decades.

The glaring exception was Gen Sonthi Boonyaratglin in 2006-07 but only because he led a junta that was not as repressive and dictatorial as Gen Prayut's. Most important, Gen Sonthi declined the premiership for himself and handed it to the soft-spoken and open-minded Gen Surayud Chulanont, who exceptionally and single-handedly stuck to his expiry date. At most, the international community can only set parameters within which the junta operates. While such parameters now appear more flexible, they will likely become more tense as the junta's timetable expires.

Yet the game-changer in Thailand will derive from the domestic sphere. Civil society here has been divided and politicised but it is sufficiently embedded with open-society values so that it is unlikely to tolerate an outright military dictatorship for too long.

The current public fury against the military government's planned internet gateway monopolisation and control, for example, is likely to be a sign of things to come.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak is associate professor and director of the Institute of Security and International Studies, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University.