The percentage of Thais in prison on charges of drug abuse - for selling tiny amounts of a drug including marijuana or having it for recreational drug use - is not known accurately. Or rather, is measured by the people who declared public support for the junta was above 99%. Conservatively, though, most would agree that if there were no prisoners incarcerated on the above charges, there would be no prison overcrowding.

This is one of the only two starting points at present for serious efforts - some already successful - to decriminalise or legalise drug offences that fall below the status of big-time drug deals.

Some efforts want to legalise them, too, on the somewhat shaky claim (second starting point) that soft drugs produce less crime and fewer deaths than hard liquor, and therefore we should encourage big-time drug dealers as regular businessmen.

This is a serious programme backed by many citizens and a few countries, including a few who claim they are not, currently, drug abusers.

The acronym-addicted United Nations General Assembly will hold a special session on drugs beginning on April 19. Naturally, is it called Ungass, and lead-up shenanigans have already begun.

A lot of countries will just sit it out, while many others, probably including Thailand, will be allowed a short statement and then marginalised onto the sidelines. Then, a tiny minority of countries and the vast majority of the 279 attending NGOs will push for legalisation.

This is how you wear down opponents and eventually achieve legalisation of drug use and drug trafficking.

Ungass has set aside a whole pre-conference day, Feb 10, for “interactive panel discussions” where countries and groups opposing legalisation can be identified and sneered at.

On all other days and at all other events, "alternatives to criminal sanctions for possession of illicit drugs for personal consumption will be discussed".

President of the UN General Assembly Mogens Lykketoft. (AP photo)

In other words, the anti-legalisation bunch have 19 days to get to New York and prepare the Feb 10 speeches. But really, no surprise.

“Have a discussion” is just code. It means Ungass is about as likely to actually discuss all opinions about marijuana as a meeting of The Kennel Association of Thailand is likely to discuss the superiority of cats over dogs.

Ungass, on the front of its own web site (www.unodc.org/ungass2016), makes it clear that every opinion will be valuable, so long as that opinion is to legalise marijuana sales. It baldly calls for civil society and citizens worldwide to “lobby your government to promote more progressive drug policies”.

The forces controlling this part of the UN are clear: resistance to legalising marijuana and other recreational drugs is futile. Pro-drug opinion has all the momentum.

Consider how Ungass frames the timeline.

There was an Ungass on drugs in 1998 where countries agreed on global drug control. In 2008, "progress [was] made on a new political declaration and plan of action", translation: halt enforcement, tolerate drug abuse.

The tipping point probably came in Thailand, in November, 2011. At an Ungass organising meeting, the Thai hosts spoke and demonstrated the world’s first and probably most successful crop-substitution programmes. Simply put: roads and free markets gave farmers more money and greater opportunity than poppies.

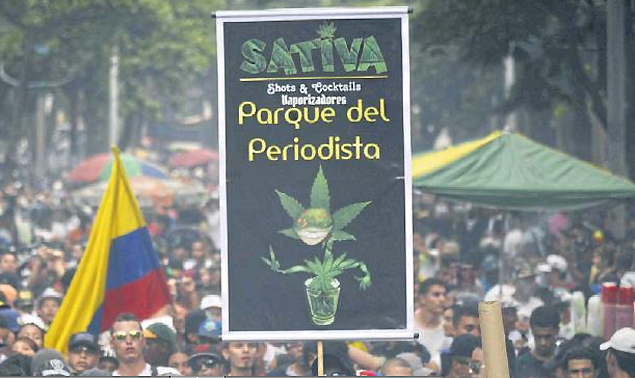

In 2012, a small group of pro-drug nations and NGOs met in Lima, Peru, and trashed the agreed Thailand model. Their plan is for free growing and marketing of coca, opium, marijuana and more, and for demoting law enforcement on drugs.

Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico insisted on moving quickly. What a surprise. Both the Mexican and Colombian supreme courts ruled in 2009 that possession of any drug for personal use is legal. Repeat, any drug. Guatemalan President Otto Perez Molina is in the process of legalising unrestricted purchase and use of marijuana and opium and opiates, translation: heroin.

Moderators and controllers of the UN “discussion” will be happy to hear all points of view that favour scaling back or shutting down enforcement, marginalising efforts against international trafficking and legalising recreational drugs.

Actually useful, medically prescribed and heavily regulated drugs such as Valium, Viagra and morphine won’t be mentioned. Strict prohibitions and long prison sentences for large-scale trafficking are fine for these. “Medical marijuana” of course should be freely available. You can’t have a UN conference without hypocrisy.

The last UN resolution on the subject recognised the intricate and increasing ties among drug traffickers, money laundries, government corruption and organised crime, including arms trafficking. The imminent Ungass conclusion will “understand new psychoactive substances”, demand that drug abuse be reduced to a public health problem and recommend every country study the lessons from Guatemala’s policy to legalise all recreational drugs.

Ungass pro-legalisation operatives will also be writing to explain to all media that they are open-minded and objective investigators and anyone who thinks they are trying to push a pro-marijuana, pro-yaa baa, pro-heroin agenda is a big poo-poo head.