As far as the masses are concerned, tobacco companies are evil. This has not thrown off the tobacco industry's efforts to wage an incarnate fight for consumers' and regulators' hearts at least since 1964, when the surgeon-general of the US declared that cigarettes had a detrimental effect on health.

After 1964, Big Tobacco realised that convincing the world that cigarettes were not detrimental to health or at least not directly linked to disease was more or less futile. As it became apparent that the government would not back down from its declaration, tobacco giant Philip Morris learned that becoming a hero to the state and anti-tobacco organisations was the industry's only way to recover from its tarnished reputation.

"We realise people don't trust us. We have a lot of baggage, which is why we are going about this in a more open and transparent way," says Philip Morris country manager Gerald Margolis, talking to the Bangkok Post about the company's smokeless product strategy, the latest in a series of public image initiatives. "People have a perception of what a tobacco company is: old people, old ways of working, old imagery. We want to change that."

Soon after 1964, Philip Morris introduced filtered cigarettes, which it claimed were less detrimental to health. Coincidentally these were also more profitable than unfiltered ones, since they contained less tobacco, and filter material was inexpensive. They also resulted in a brief spike in sales, before cigarettes returned to the downward trend they have kept up in the United States to this date.

Margolis at Doi Suthep with family

In the 1970s, cigarette makers voluntarily removed all advertisements from television and radio, three years ahead of a proposed deadline. Partly because companies wanted to use it as a leverage to gain exemptions from antitrust regulations, and partly because they were afraid of putting health warnings on screen. Advertising on TV was misguided because it reached too many children, said an executive at the time.

In 2009, Philip Morris executives celebrated the regulation of tobacco sales by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a development that was universally praised by anti-tobacco groups. The bill placed more stringent requirements on marketing campaigns and the composition of cigarettes, and the money to enforce the regulations came in large part out of Philip Morris's pockets. However, according to Philip Morris's rivals, the world's largest cigarette maker by value deters competitors from mounting campaigns that could have diluted its market share.

Tobacco companies benefited from working with the government, even though they did suffer harm from regulation. The percentage of adult males that smoke fell from 42% (81 million) to 16.8% (53 million) in the US from 1964 to 2014. Declining sales in the US have been propped by sales in the developing world, especially in Asia-Pacific. Close to 2 trillion cigarettes were sold in 1960, and a little over 5 trillion in 2014, which suggests that there has been a slight increase in the number of smokers worldwide, despite drastic declines in smoking rates in Europe and the US.

As the region catches up with developed countries' regulatory schemes, tobacco companies may no longer be able to rely on these markets as growth avenues. In Thailand, home to some of the most draconian tobacco regulations in the world, the percentage of smokers among the general population fell from 26.9% in 2011 to 20.7% in 2014, according to the National Statistical Office. According to surveys conducted by that office in 2014, 2011 and 2007, close to 100% of the population in Thailand knows that smoking can cause serious diseases, including cancer.

The meeting rooms of Philip Morris's newly renovated offices still bear the names of some of their flagship products, including Marlboro, the top-selling cigarette brand worldwide. The business card of country manager Gerald Margolis, however, bears the slogan "smoke-free future".

Throughout the interview, Mr Margolis pushes the narrative that people should not start smoking, and if they have already started they should try to stop. For those that, for some reason or another cannot or will not, smokeless products provide a "potentially less-harmful alternative" -- a carefully crafted statement meant to comply with the requirements of the FDA, which has yet to approve the products.

"We want to give a potentially healthier alternative to the 11 million Thai smokers," Mr Margolis says. "It's okay for consumers to choose our product over those of our competitors. If we didn't do it the right way, then someone could step in and do it the wrong way."

The company is working on "educating the government on the benefits of smoke-free products, changing their mindset, and ultimately having the higher-ups change the law".

This is neither the first nor the last time that Philip Morris has attempted to recast itself as the standard-bearer of extra-legal morality.

Mr Margolis at a Thai temple with his family.

The latest move, while possibly benefiting consumers, may also feature the wonderful coincidence of reinforcing the company's already robust balance sheets.

The largest sticking point of the tobacco giant's smokeless strategy is that its traditional cigarette business, its revenue and profit driver, does not have an expiry rate. "We owe it to our shareholders to be successful in the traditional cigarette business, the only one in which we can compete and make money," Mr Margolis says. "We will stop selling as soon as we can, but we need the government's help."

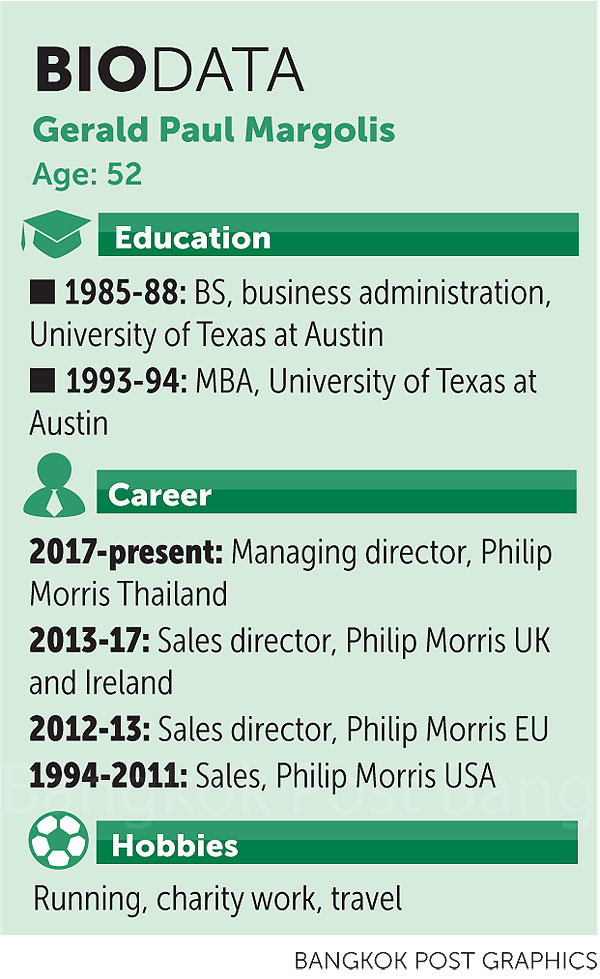

Mr Margolis, who is seven months into the job, is the poster child of the cigarette maker's smokeless campaign. The 52-year-old executive doesn't smoke, and he drinks coffee only "casually".

"Tobacco is just not a product that I enjoy using, or that has ever attracted me. The negative health impact is also a consideration," he says. "I am not a saint, though. I like my Leo and my Chang, and a cocktail on weekends. But I like to drink water and juices, hit the gym and live a generally healthy lifestyle."

The executive has run four marathons, one full Ironman triathlon and a slew of half-Ironmen.

Mr Margolis came to Philip Morris after earning two degrees at the University of Texas at Austin and doing a three-year stint in the Boston office of Price Waterhouse, which became PricewaterhouseCoopers in 1998 after a merger. He also tried out stand-up comedy while in Boston.

"The first time was bad," he says. "I got too confident the second time and it turned into a disaster."

Mr Margolis still carries an indelible smile, whether talking about his time as an intern in the 1990s, or about research on tobacco's harmful effects. The jeans-clad executive is courteous as he treads a fine line between promoting the business and conveying the measured and self-righteous attitude the company seeks to establish.

Mr.Gerald Margolis, Managing Director of Philip Morris (Thailand) Limited SOMCHAI POOMLARD

The rate of smokers among company employees, he says, is similar to that among the general population.

"We realise we are a controversial industry," he says. "So we make a point of asking employees whether they would have any issue working with us. They should think about what their friends and family would say."

His journey with Philip Morris started in Los Angeles and took him through sales positions in the US and England before landing him at the top post in the company's Thailand office. Never in his 24-year career in tobacco has he had any ethical questions about working for the company. Nor does he have any professional regrets.

"When I was an intern, I was told pretty adamantly that I couldn't put balloons in advertisements, even if it was legal, because it would be attractive to kids," Mr Margolis says. "This company always goes beyond the letter and spirit of the law."

Throughout his career, Mr Margolis has faced a rapidly changing business environment, which left companies like Philip Morris with little to no avenue to promote their products.

Back when he started in California, tobacco companies would advertise at sporting events and had "all kinds of freedoms" to market their products. In Thailand, tobacco advertisements are prohibited. Cigarette packets must carry health warnings that occupy 85% of the package's space.

"Over the years, a lot of the freedoms we had went away," Mr Margolis says.

In Thailand, as in England, he faces a highly regulated market, making things challenging but also rewarding. Smokeless products are a wholly different business, with expensive devices and accessories.

"I think my greatest achievement would be getting to a place where we can sell in Thailand," Mr Margolis says.

The smokeless business itself may allow Philip Morris to consolidate its market share by pushing ahead of smaller, less tech-savvy competitors. In the markets where it has introduced the products, such as Japan, Philip Morris's portion of tobacco product sales generally increased.

Furthermore, "potentially less-harmful products" may help reverse or at least stop declining smoking rates around the world, even if the company has to prove that these products do not appeal to non-smokers to gain approval by the FDA.

Most importantly, the move has the potential to reduce the taxes and marketing restrictions on the products.

Mr Margolis faces a steep hill in Thailand, where the government has a vested interest in the tobacco industry through the Thailand Tobacco Monopoly.

"We have a chance to shape the law, but today there are too many people that are so opposed to smoking that they will dismiss anything that seems or looks like it," he says.

Launching the company's smoke-free products in the Thai market will be the executive's last job.

"I love the night markets and the day markets, and we are taking advantage of this opportunity to travel around Asia," he says. "I won't go until they make me go."

Retirement, however, is still not on the table for Mr Margolis.

"Now that you've mentioned it, I will go home and think about retirement. For now, my wife wants me to keep working."

Mr Margolis is seven months into his job as country manager for Thailand at tobacco giant Philip Morris.

Mr.Gerald Margolis, Managing Director of Philip Morris (Thailand) Limited SOMCHAI POOMLARD

Mr Margolis discusses with a staff. SOMCHAI POOMLARD

Mr Margolis has spent 24 years in the tobacco industry.

Mr Margolis and family on an elephant sightseeing tour.

Tie and die workshop in Phrae.

Mr Margolis and family in Bangkok's Chinatown.