Alphabet Inc.'s Google has crushed almost all its competitors in the world of digital-advertising technology. But one rival is emerging as the best hope to challenge the tech giant--if it manages to keep up its momentum.

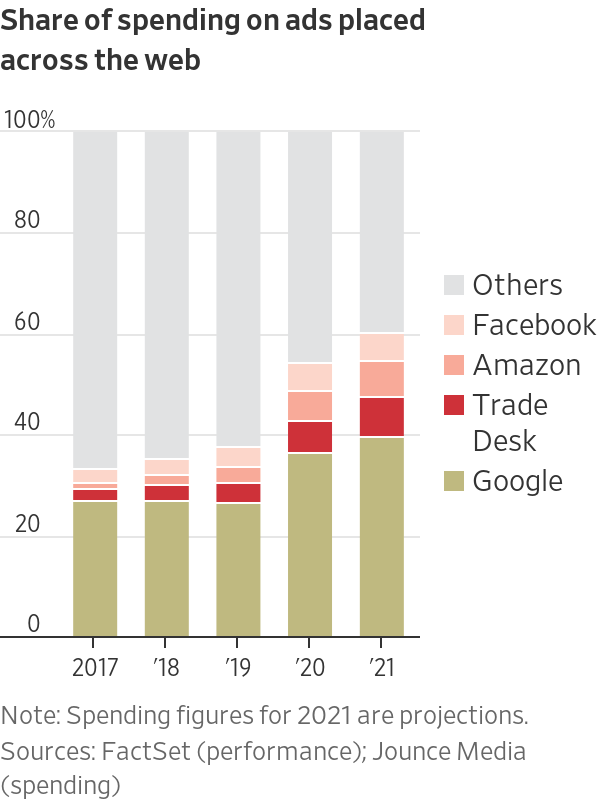

The Trade Desk Inc., which specializes in helping companies buy online ads across publishers' websites, has done what others failed at: eating into Google's share of the market. While Google dominates that area of ad-buying with about 40% of the business, Trade Desk is up to nearly 8% and its share is growing faster than Google's, according to ad-tech consultancy Jounce Media.

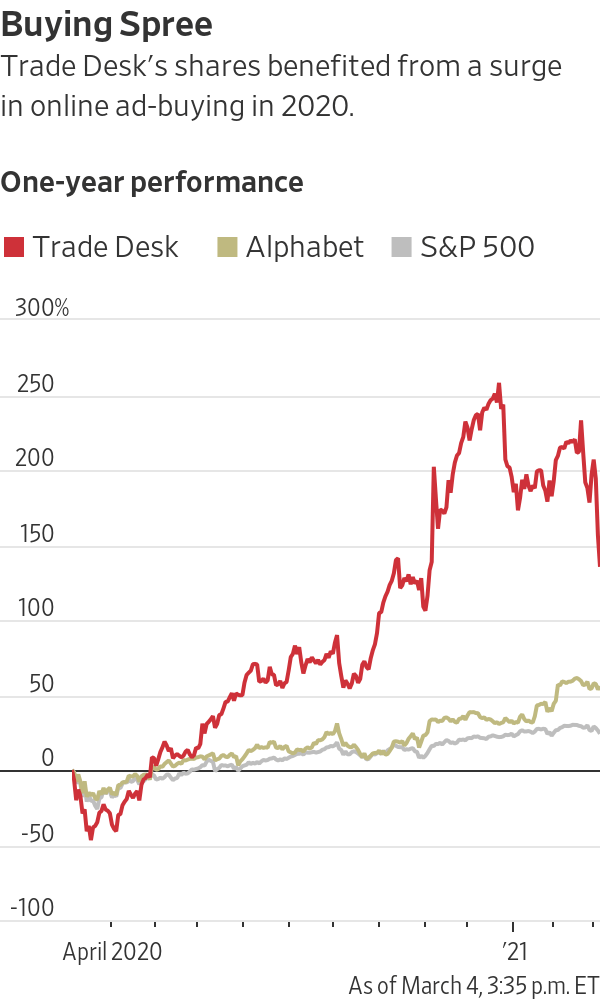

Trade Desk has made inroads versus Google by investing in online advertising segments like audio and streaming TV where Google hadn't already cornered the market. Pandemic-struck 2020 was especially good for business. Homebound Americans consumed more digital media. Brands moved money from TV advertising to digital. Trade Desk revenue shot up 26% compared with 2019, hitting $836 million.

Investors saw Trade Desk as a Covid-resistant safe haven, and it was one of 2020's top performing stocks, with a tripling in its share price. With a $30 billion market capitalization, the Ventura, Calif.-based company is worth about as much as the two largest ad-agency conglomerates combined.

Trade Desk Chief Executive Jeff Green embraces the company's role as the anti-Google, but has no illusions about how difficult it is to take on the tech powerhouse. For starters, Trade Desk is competing in only one corner of the ad market: Most of marketers' dollars flow directly to Google and to other big tech platforms' own properties, like YouTube and Search, outside of the reach of companies like Trade Desk.

Google's announcement Wednesday that it will end targeting of ads based on individual users' web-browsing behavior, and focus on targeting based on larger groups or "cohorts," could pose risks for Trade Desk. Billed as a privacy move, the change could actually play to Google's strengths, Mr. Green and others in the industry say, because it has so much other data on consumers to use for targeting ads.

"They are leaning on an advantage that they have from very big near-monopoly businesses so that they can provide targeted advertising while they're taking steps to inhibit others' ability to provide targeted advertising," Mr. Green said in an interview.

Antitrust authorities in the U.S. and abroad are investigating various elements of Google's business. "This is a big move that should be looked at," Mr. Green said of Google's new targeting policy.

"We do not believe ad tracking across the web meets the needs of consumers," a Google spokesman said in a statement, adding that the company will support ad targeting that uses "first party" data that companies collect on their customers. "First-party relationships have always been critical for brands to build a successful business, and it'll become even more vital in a privacy-first world."

Trade Desk's stock fell nearly 13% on Wednesday as investors worried Google's announcement would reshape the industry at Trade Desk's expense. Mr. Green said the firm has an opportunity to build an alternative targeting technology that can be the main rival to the approach Google is laying out.

Mr. Green, 43 years old, has beaten the odds before. He grew up in a strict Mormon family of five children in Salt Lake City, drifting between poor and lower middle class, and has memories of standing in line for government assistance. The University of Southern California graduate worked in ad tech, then founded two ad-tech startups and sold the second one to Microsoft Corp.

He founded Trade Desk in 2009. He made the company profitable after raising $7 million in venture capital, and had raised $120 million by the time of its 2016 initial public offering. Mr. Green holds 53.5% of his company's voting power and 10.75% of its stock, a stake valued at about $3 billion. He has enjoyed his wealth: He has several cars, with the "most exciting one" a white Porsche Taycan, he says.

He has also been an aggressive philanthropist: He funded a scholarship program at California State University Channel Islands, where about 90% of students qualify for federal Pell grants for low-income students. The program started two years ago and now has funded 47 scholarship recipients, who have mentored 1,416 freshmen to date. Mr. Green also is committed to building a school in Nicaragua.

In online advertising, there are tools for every stage of the ad-placing process--putting space up for sale, auctioning it and interfacing with buyers. Trade Desk focused squarely on the buying side, betting it could persuade clients it wouldn't be burdened with conflicts from playing on all sides of the marketplace.

"When you go into a grocery store, you should be able to choose what you want to buy, not necessarily what the grocer wants to sell you," said Steve Katelman, executive vice president of global digital partnerships at ad-agency holding company Omnicom Group Inc.

Trade Desk forged direct relationships with publishers and media companies like Comcast Corp.'s NBCUniversal, Condé Nast, Fox Corp., Wall Street Journal parent News Corp., Spotify, TikTok and Vox Media, gaining the right to post their ad space directly on The Trade Desk's systems. Those arrangements cut out the middlemen in ad transactions, pleasing buyers and sellers.

Next year, Trade Desk will face a big challenge when Google removes third-party "cookies" from its market-leading Chrome browser. Cookies are text files advertisers and publishers use to amass data on users' web activity that can inform how to target ads.

Google's decision Wednesday to move away from individualized user tracking in its own ad operations means digital advertising could bifurcate, with a Google ecosystem that has one set of rules and the rest of the web following another.

"There is a more stark contrast now between the open internet and Google than ever before," Mr. Green said.

To offset the loss of cookies, Trade Desk is recruiting publishers and ad-tech companies to create a new identifier for users, Unified ID, which would be compiled from your email address but scrambled to protect your privacy. Any company in the network would be able to access a user's Unified ID profile and contribute data to it. Unified ID already has profiles for 50 million people, a Trade Desk spokesman said.

Google said Wednesday that it wouldn't use any such alternate identifiers and that they wouldn't meet consumer or regulatory expectations for privacy.

"It's a strategic mistake for Google to get rid of cookies, because to me, they're using privacy as a reason to do something that does not foster competition and is bad for the open internet," said Mr. Green.