Large companies are no longer cool. The modern business model is tilted towards the concept of sharing, and with the advent of cutting-edge technological innovations, businesses gain benefits while a larger customer base keen to lower risks is helping upcoming players.

A sharing economy is a business concept whereby individuals and even businesses can turn their assets into cash. Monetising and maximising their assets to eliminate excess offers cost-effective alternatives to traditional products and services.

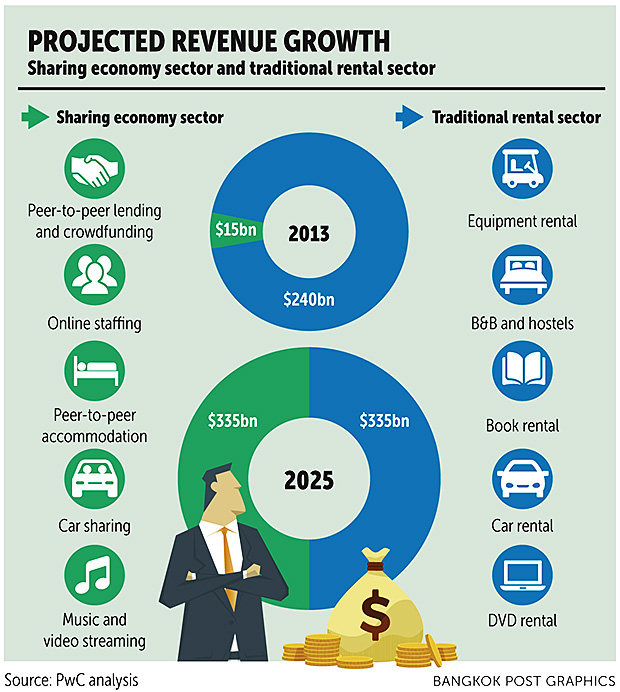

How big can a sharing economy become? PwC predicts that the sharing economy across five key areas -- travel, car-sharing, finance, staffing and streaming -- will total US$335 billion (11 trillion baht) within eight years, accounting for 50% of those markets. Currently they account for 5%.

Changing to survive

The food and hospitality sectors, in which established conglomerates are bleeding market share to smaller local players, are proof that large is not hip.

Young consumers are shifting away from the Marriotts of the world to local brands, eschewing hotel restaurants for Instagram-able local food stalls.

While some companies wage expensive marketing campaigns to ingratiate themselves to millennials, others are betting that acquiring up-and-coming brands connected to this customer segment is a step towards future prosperity.

For example, small independent brands like Kind Bars, which does not use preservatives in its products, are being chased by the likes of Kellogg, PepsiCo, General Mills and Mars.

For drink makers, acquisitions may be the only way of maintaining their growth, as consumers move away from sugary drinks to healthier alternatives. Demand for soda, including non-calorie alternatives, has been falling for 10 years straight in the US.

As demand for traditional drinks lags, global players like Coca-Cola and Pepsi are adding alternatives to survive.

Pepsi recently acquired Kevita, a maker of probiotic drinks, which contain "healthy" microorganisms, for $200 million. Coca-Cola, in turn, has entered the rapidly growing coconut water market through its acquisition of Zico, introduced to Thailand in the last quarter of 2017.

The hospitality industry is undergoing a similar transformation, rattled by the effects of Airbnb, which has a market capitalisation of $30 billion -- already larger than Hilton's and a tad smaller than Marriott's. Airbnb offers consumers the experience to stay like locals at a fraction of the price of a hotel room.

Not long ago, executives of large hotel corporations boasted that their competitive advantage over home-sharing services was consistency, which they said would make guests feel at home whether in Jakarta or New York.

Consumers, though, are increasingly looking for unique experiences and interaction with locals, something hostels and boutique hotels are adept at, but big chains ... not so much.

For example, Thailand-based hotel group Dusit Thani is moving into the boutique hotel space through its Asai brand, which is 30-50% cheaper than the company's traditional offerings, said Siradej Donavanik, chief executive of Asai.

The newly branded hotels, located on sites of roughly 780 square metres, allow the firm to place them in city centres such as Tokyo. Rooms are small, with emphasis placed on common spaces and locally sourced food.

Mr Siradej plans to roll out 10 hotels throughout Asia this year, with an additional 10 each year after that. At this pace, the segment will soon be larger than the group's 27 properties. The new chain will cater primarily to the 200 million travelling millennials, a group projected to expand to 300 million soon, Mr Siradej said.

While Dusit Thani is the only Asia-based brand to move into this sector, its competitors across the Pacific have been re-positioning themselves for years now.

Hilton's Tru and Marriott's Moxy are among the fastest-growing hotel chains in the US, and they have started to expand elsewhere. Moxy has two locations in Japan and one in Indonesia.

Boutique hotels and organic local food not only sell better, but they are much more profitable than their traditional counterparts. The most distinctive component of millennial-driven products is that they are different and provide a unique experience.

This emphasis on differentiation allows drinks companies to escape the economics of heavily commoditised products like soda and move into thicker-margin offerings.

In the case of the hotel industry, the focus on boutique hotels has made them favourites among private equity firms and financial analysts.

Hilton's Tru even eliminated coffee makers to make cleaning more efficient. Mr Siradej said margins at the new Asai brand are up to 50% higher than those of full-service hotels.

Robust margins may be essential to compete with the growing sharing-economy giants, which operate with light assets at a high profit. Airbnb's margins, for example, are estimated at 10-15%, close to double those of the average hotel operator.

Sharing for mutual prosperity

Toyota Motor Corporation recently announced that it would invest $1 billion in Grab Holdings Inc, the Singapore-based ride-hailing service provider, to expand their collaboration in Southeast Asia.

For Thailand, the Grab mobile app provides various types of car-sharing and ride-hailing, such as public taxis, private cars and private motorcycles. Grab also offers a food delivery service.

Research analysis from Siam Commercial Bank Economic Intelligence Center (SCBEIC) found that car-sharing service still faces several challenges in Thailand compared with other countries such as Germany, France and the US, due to a shortage of dedicated parking space for car-sharing, limited public transport coverage and a lack of environmental policy linking CO2 reduction with the transport sector.

The think tank sees a shift in consumer perception on car ownership in some countries, especially among Gen Y consumers, but this trend is not yet evident in Thailand.

According to a 2017 survey conducted by SCBEIC, car ownership ranked as the top acquisition wish among Thai first-time workers. However, consumer preferences may shift once ride-sharing and delivery services such as Grab and Line become more convenient and ubiquitous.

In the short term, SCBEIC believes Grab will cement its market-leading position in Thailand with investment capital from Toyota.

Toyota could benefit from the stream of data from ride-hailing service drivers, supporting new business ventures. In particular, autonomous driving requires a large amount of data for learning, while insurance businesses under the mobility-service platform could also use the data.

Nantapong Pantaweesak, an SCBEIC analyst, wrote an article titled "Readiness Check for Car-sharing Businesses" noting that transport options, such as taxis, motorcycle taxis and ride-hailing services, are more competitive because of higher flexibility in both the process of acquiring a ride and parking, as these services come with a driver.

The government's taxi price regulations work against car-sharing businesses and are not conducive to competition in the transport market, contrary to countries with strong car-sharing businesses such as Europe and the US, Mr Nantapong said.

Car-sharing fees for travelling less than 10 kilometres for 30 minutes or less are 10-20 baht higher than those of taxis.

Though taxi fees are much higher in Europe and the US, their governments provide incentives for people to use car-sharing services instead of using personal cars to support environmental policy goals.

Motoki Yanase, vice-president for the corporate finance group at Moody's Japan, said Toyota's investment in Grab is credit-positive for both parties.

The deal will enhance Toyota's foothold and capability in ride-hailing services, a fast-growing business that could alter automakers' traditional business models. Grab will in turn benefit from Toyota's technological capability.

Toyota's driving recorder, which collects driving data and stores it in a central platform, will expand connectivity among Grab's rental car fleet across Southeast Asia. This data will help the two companies roll out new services for drivers, including automotive insurance, auto leasing and vehicle maintenance.

This collaboration complements Toyota's existing alliances with global ride-hailing providers, including Uber Technologies Inc and JapanTaxi Co, an app-based provider in Japan. Grab has strengthened its leading position in Southeast Asia after acquiring Uber's assets in the region in March.

Led by young users, ride-hailing services have gained popularity in Southeast Asia.

"Toyota is poised to benefit from its growing presence in this business because new car sales in the region could fall amid changing consumer preferences and increasing acceptance of the app-enabled sharing economy," Mr Yanase said. "We estimate that Toyota has more than a 25% market share and a leading position in Southeast Asia, making it an important market for the company."

For Toyota, the $1-billion investment is small relative to its annual cash flow from operations for the automotive business, which Moody's estimated to exceed ¥2.5 trillion (748 billion baht) for fiscal 2018, which ended in March.

Toyota first invested an unspecified amount in Grab in 2017 through its trading company, Toyota Tsusho Corporation.

Realising the lucrative potential, other Japanese companies have also begun to invest in ride-hailing service providers.

Honda Motor Co invested an undisclosed amount in Grab in December 2016 for motorcycle-sharing services in Southeast Asia, while SoftBank Group Corporation has invested in Uber, Grab, Chinese ride-hailing service provider Didi Chuxing and Indian ride-hailing company Ola Cabs.

Technology is key

Despite a healthy market in Thailand's property sector, large developers have adjusted before being disrupted, said Apichart Chutrakul, chief executive of SET-listed developer Sansiri Plc.

"The property business model is changing," he said. "In the future, artificial intelligence [AI] may analyse land plots and tell us what kind of property would derive the maximum benefit. If developers do not change [their business models], they will be unable to keep up with others."

Late last year, Sansiri joined six diverse companies to cooperate on technology and lifestyle after partnering with BTS Group Holdings Plc and Japanese railway operator Tokyo Corporation for condominium development.

Atip Bijanonda, president of the Housing Business Association, said developers' partnerships with non-property businesses like technology or energy savings are a marketing tool to attract homebuyers.

"Developers find new marketing gimmicks as a new sales point," Mr Atip said. "But this does not mean [property] projects without [partners] will not be able to sell their units. Homebuyers still consider fundamental factors when buying a house."

Those factors include location, price and overall value. Marketing gimmicks are not the key factor in homebuyers making a decision, he said, citing solar rooftops, which add development cost to the housing price.

Ultimately, all market segments need to adopt technology or non-property partners to increase the value of their products and meet consumer preferences, though their behaviour changes rapidly, Mr Atip said.

Tachaphol Kanjanakul, governor of the National Housing Authority, said technology plays a key role in residential development in all segments and is not confined to specific markets as in the past.

"We are adopting technology to improve the residential quality of units in the lower- to middle-income segment as well as for seniors," Mr Tachaphol said. "We have partnered with CAT Telecom to study and develop smart homes as part of the government's 4.0 policy."

Krating Poonpol, managing partner of 500 TukTuks, the local arm of the US-based venture capital firm, said that having large corporations invest in its fund helps not only with fund-raising, but also allows such large firms to connect to their customers and offer domain expertise.

Distributing equal risk factors is another advantage of such business partnerships, Mr Krating said.

500 TukTuks' two funds have at least 10 corporate partners who operate in the retail, fast-moving consumer goods, logistics, media, IT, energy and industrial sectors.

500 TukTuks create sharing economy platform with leading business groups, namely Central, TCP, Thairath, Saha Group, and the South East Insurance Company. (Photo by Weerawong Wongpreedee)

Sumet Ongkittikul, research director for transport and logistics policy at the Thailand Development Research Institute, said the sharing economy for logistics and delivery services is still emerging because usage remains limited.

Online delivery services such as food delivery are quite popular among urban dwellers because of the convenience and traffic jams, Mr Sumet said. But the service is mostly limited to millennials and the fare paid by distance is not cheap, he said.

When logistics efficiency is enhanced, these platform providers will have the power to control the price, Mr Sumet said.

As for online taxi and car-booking services, they are unlikely to become widespread quickly because there are many traditional taxis in Bangkok and hailing them remains convenient, he said. They provide a more useful service in locations where it's hard to access traditional taxis.

Past is prologue

In the financial industry, the concept of a sharing economy has been implemented over three decades among financial institutions. ATM pools and electronic data capture (EDC) pools are classic examples of a sharing economy here.

When ATMs were first introduced in Thailand, cardholders were only allowed to withdraw cash from machines owned by the issuing bank. ATM cardholders of Bank A could not withdraw money from Banks B or C, while credit card holders of Bank C could not make credit card payments at a superstore if it did not have an EDC machine from Bank C.

Banks made lavish investments to set up huge ATM and EDC networks to serve their customers, but that ended when the Thai Bankers' Association initiated an ATM pool, followed by an EDC pool, allowing smaller banks to share ATM transaction expenses with larger players.

"The basic idea of a sharing economy is to reduce financial costs and time spent for all participants," said Peainkrai Asawapoka, president of JP Insurance Public Co and executive director of the Thai Fintech Association. "One group owns an asset that is not used for a period, while another group does not own the asset but wants to use it for a period.

"Technology helps in three ways: reduced cost, increased speed and increased efficiency."

For its part, the insurance industry is discussing implementation of a sharing economy such as sharing resources for accident claims, Mr Peainkrai said.

At present, when an accident occurs, car owners must wait for insurance employees to finish the claim for both parties. In the future, if insurance companies can pool a claim resource, the claim might be processed via a surveyor or anyone who is nearest to the accident and can use an integrated system.

This is akin to folks with ATM cards that can withdraw money from any ATM machine, no matter the bank that owns the machine, Mr Peainkrai said.