Members of the household kept sneaking off with this book but were betrayed by their giggles and sighs of nostalgia. It is great fun. Its creation was clearly a labour of love and joy. But it is also the work of a serious and skilled historian.

Nicolas Verstappen is teaching in the Faculty of Communication Arts at Chulalongkorn University. He found his sources for this book in earlier studies by Thai authors, in archives and private collections, and in hoards of clippings unearthed from storerooms and attics. He tells the story of Thai comics from 1907 to the present in 40 chapters, of which 30 focus on a particular artist or team, and the others on a publication, group or theme. He starts by noting Thailand's rich inheritance of tales, many of which mix the real and the surreal -- a feature that provides the magic of cartoons everywhere.

The first cartoons appeared in parallel with the growth of newspapers in the early years of the 20th century, starting with spreads of two to six panels, and expanding into long-running serials by the 1920s. The early artists were enthusiasts who taught themselves, often from imported newspapers and magazines. Later, several were trained in the Poh Chang School of Arts and Crafts. They found their plots from Thai tradition, particularly Jataka stories and folktales, with Sang Thong and Kraithong being clear favourites. Their work combined entertainment and moral instruction. They borrowed from the world, with Popeye making his debut appearance in Ayutthaya history in the 1930s.

This phase climaxed with the work of Prayoon Chanyawongse, who brilliantly adapted the conventions of likay folk theatre into the format of the comic strip. He included the likay audience in the narratives in a way that was postmodern before its time, and he flirted with the commentary on contemporary politics which is a hallmark of Thai popular performance.

After World War II, the market for comics expanded as the economy grew and literacy spread. Magazines multiplied. Graphic novels appeared in the 1960s. The artists slipped their moorings to traditional literature and turned to stories of contemporary life and modern fantasy. In the era of US influence, the artists borrowed the Lone Ranger, Elvis, Superman, Captain Marvel and characters from MAD magazine.

More of the artists came from the ranks of people migrating into Bangkok, especially from the Northeast. The comics began to reflect the mixture of optimism and apprehension which the city inspired. In 1960, Tawee Witsnukorn drew a comic version of Thailand's most famous ghost story, Mae Nak Phrakhanong, beginning a wave of stories exploiting Thailand's huge range of spirits and ghosts, especially the hideous Krause with her disembodied head and dangling entrails. During the political upsurge of the 1970s, some artists turned to social realism. Chai Rachawat's series on Thung Ma Moen village in the Thai Rath newspaper is perhaps the best-recognised of all Thailand's newspaper cartoons. Triam Chachumporn translated the spirit of Song For Life into comics with true-life stories and beautifully realistic illustrations.

Around 1970, somebody fashioned a new format of a small-size 16-page booklet priced at 1 baht. The market exploded. At the height, a million copies of 1 baht comics were being sold every month. One surviving collection has 40,000 titles. Many people were sucked into the frantic process of production, including an army colonel who drew overnight. Around 40% of the output were ghost and horror stories, followed by tales of crime and revenge. These 1 baht comics offered many people an everyday escape from the reality of a tough life. By 1980, they were criticised for their increasingly trashy content. Government agencies and publishers launched calmer, more educational alternatives, particularly the magazines Darun Sarn and Chaiyapruek, which were rather successful.

By 1986, the 1 baht boom had collapsed, felled by television and Manga. Television ownership had become near-universal, and cartoons were a prominent and popular segment of the programming. Manga began arriving from Japan in the late 1960s, and in a much bigger volume from the late 1970s. Doraemon debuted on Thai TV in 1980 and, as elsewhere, quickly became a cultural phenomenon by reflecting the wonderment at the modern world felt by children of all ages. Thai entrepreneurs first pirated and then copied Manga but by the 1990s the import was regularised and massive.

The market for Thai comics shrank. Some artists and entrepreneurs survived in creative ways. The music producer Boyd Kosiyabong exploited the synergies between music and comics in a widening youth market. Several cartoon artists adapted Manga styling into themes with an appeal to Thailand's millennial youth. In 1998, Suttichart Sarapaiwanich invented Joe the Sea-Cret Agent, combining elements of Western noir and Japanese Manga. His squid-headed humanoid spy-cum-detective hero lives in a water-logged future and pursues adventures all over the world -- reflecting this generation's embrace of the globe as well as its apprehension about the future.

The final part of this book showcases the enormous creative talent now engaged in drawing cartoons and comics, but also the difficulties in publishing them. The artists are now often trained in tertiary colleges offering courses in graphic arts and have the confidence to be personal and experimental. Some successful magazines such as a day give space to comics, but otherwise, the publications have limited circulation and very short half-lives.

Verstappen ends with a short essay asking whether there are any "uniquely Thai qualities" in this century of Thai comics. His answer is that the capacity for borrowing and blending is the distinctive Thai contribution. But the traffic has been all one way. Thai comic artists have imported Superman, Captain Marvel, Mickey Mouse, Elvis and many others but in return have exported only a solitary hideous Krause. But perhaps that will change with the new generation beginning to caption in English.

This is a superb and surprising book. There are editions in both English and Thai. Illustrations appear on almost all of its 275 pages with long captions that overcome the need to read Thai. The capsule biographies of the artists are a slice of social history in themselves. The text is beautifully edited and the stitched binding is solid. There is an excellent index and a useful bibliography. A fabulous book.

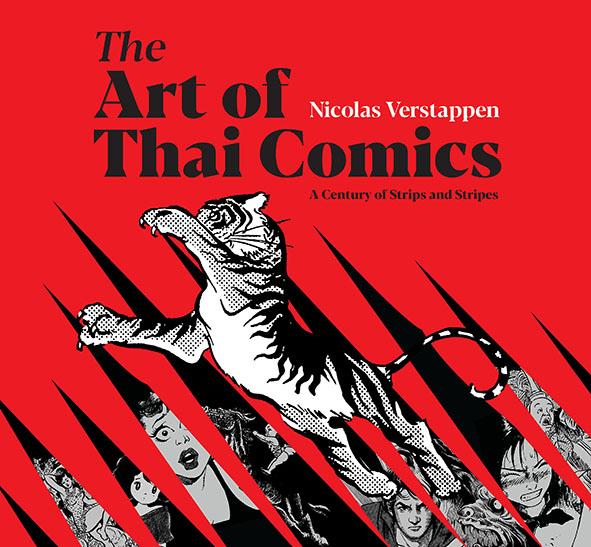

- The Art Of Thai Comics: A Century Of Strips And Stripes

- By Nicolas Verstappen

- Bangkok: River Books

- 1495 baht