While picking up a bottle of cancer drugs from her desk, a nurse jokingly mentioned how we had to handle it with utmost care. Each bottle, which lasts 30 days, costs as much as half a car, she said. Almost four years ago, I was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer. This means the disease has already spread to other parts of my body such as my bones, and it is incurable.

My doctor has been so kind to search out all possible means to take the best care of me. He asked if I was interested in participating in a research programme on a target therapy medicine which gained fast-track approval by the US's Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but was not yet in Thailand. I gave my consent right away, even though I was not aware how super-expensive the drug was.

As part of the trial, the pharmaceutical company sponsored the cost of the drug plus periodic check-ups such as CT-scans and bone scans as well as chemotherapy for some patients.

In the beginning, I was assigned "the best chemotherapy treatment". After six sessions, there was a three-month waiting period to see how my cancer cells responded to chemo drugs, and finally my doctor decided it was time to put me on the target therapy drug. Unfortunately, right from day one, my body developed a severe allergic reaction to the drug that worsened my condition. My doctor then put me on another programme with a different pharmaceutical company, that has been found to help other patients who failed to respond to the first drug. (There was, however, a three-month waiting period in which the cancer spread further to some parts of my brain.) Three days after receiving the second drug, I started to improve.

It has been two years and seven months since I began taking the second drug under the "compassionate use" programme. This means I do not have to cover the cost myself (which I learned later, is even more expensive than the first drug). Although it cannot cure me of the disease, my condition has become more stable. I can still walk slowly, sign my name on legal documents, write a book and so on. Otherwise I am not sure which condition I will succumb to first, bankruptcy or cancer.

But I do not want to enjoy the privilege alone. I witnessed the deaths several years ago of my two brothers, Ta and Teaw, who had cancer. Ta spent his last few months in a private hospital; when he died, his children could not even afford to pay for his grave.

Teaw, who had worked all his life as a farmer without many savings, opted for herbal remedies and still suffered miserably until his last days. Both my brothers represent the general public who work hard all their lives, but whose incomes do not provide much to cover their medical care. Thais can gain access to medicine on the National Essential Medicine (NEM) list, but if they want any "special treatments", they have to dig into their own wallets. That's despite the fact we have a universal healthcare system which is supposed to provide broad coverage.

Can the government allocate more funds to the Public Health Ministry, in particular to support research and development (R&D), so we can one day develop a body of knowledge and products for treating such diseases ourselves? The lack of necessary hospital equipment prompted rock singer Athiwara Khongmalai ("Toon" BodySlam) to launch a nationwide marathon to raise funds for financially troubled hospitals. Media reports indicated that a number of state hospitals across the country are in the red, the amount of debt ranging from 92 million baht to 354 million baht. How many more marathons can Mr Athiwara stage to salvage them?

Another intriguing statistical paradox: in the 2018 fiscal year, the national budget allocation for the Health Ministry is 136.1 billion baht, whereas the Defence Ministry gets a bigger budget share with 222.5 billion baht. With such a budget, there is little left for researchers to undertake R&D into cancer or any other fatal diseases. There are also a host of other barriers that inhibit them from developing generic drugs such as by modifying brand-name drugs.

One constraint is the "evergreening of patents", a tactic employed by pharma giants to extend the expiring patents on their drugs so they can retain royalties which normally last for 20 years. How can they do that? The companies reapply their patents by taking out new patents over associated delivery systems for the same drugs, or for some slight change in the pharmaceutical mixtures that include the same drugs. There are many other means but the end result is the pharmaceutical conglomerates can prevent their competitors from doing research or developing new products based on those originally patented for longer periods of time than would normally be allowed by law.

In my heyday in journalism, I used to cover the struggle for the public's "right to medicine", writing extensively about the Free Trade Agreement (FTA), the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Rights (TRIPs), and the Doha Declaration which stipulates how medicines are goods for humanity, not luxury goods, so there should be mechanisms (such as compulsory licensing) that enable developing countries to produce affordable drugs for patients in critical need.

There are other related laws, but I just hope officials at the Intellectual Property Rights Office carefully study the World Health Organisation's handbook to help find ways for local researchers to handle the application and re-application by pharmaceutical conglomerates for their brand-name drugs. With better R&D and other support for local researchers, I envisage a day when patients of cancer or other serious diseases can have access to effective drugs that improve their quality of life without ruining them financially. After all, the treatment of cancer should not be a privilege.

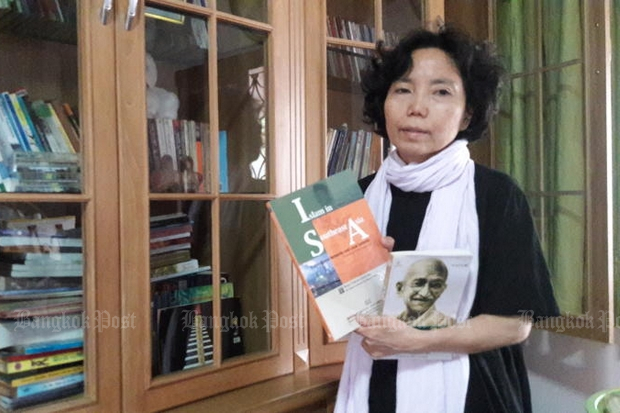

Supara Janchitfah is a former Bangkok Post journalist.