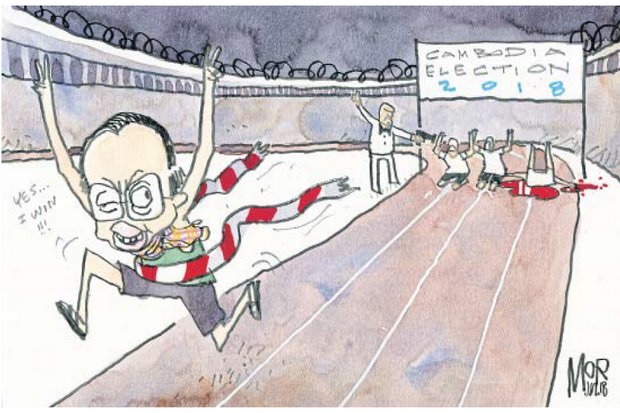

It was always a foregone conclusion that Cambodia's incumbent government of Prime Minister Hun Sen and his Cambodian People's Party (CPP) were going to win the July 29 election. Yet some observers anticipated a modicum of feigned legitimacy whereby a handful of smaller parties would gain a few seats in the National Assembly. Not bothering with any semblance of legitimacy, the CPP has apparently claimed all 125 parliamentary seats. Cambodia now has an elected dictatorship, naked and bare, in mockery of what passes as a free and fair election anywhere and in defiance of global democratic aspirations.

At issue is how the international community will respond to Hun Sen's dictatorship in the interim and how the dissolved opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party fares going forward. What we do know is that the Hun Sen regime will further entrench itself, that China will sign off on Cambodia's poll outcome, and Asean will stay muted on the sidelines.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak teaches International Relations and directs the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University.

The preliminary poll numbers represent a dark farce. According to Cambodia's eager and gleeful National Election Commission, voter turnout was more than 80%, with the CPP garnering most of the votes. The 19 smaller parties won just small fractions here and there, although initially it appeared that Funcinpec and the League for Democracy Party may have gathered enough support for a few seats.

While final results will be announced subsequently, it is clear the CPP will rule for another five years without any effective parliamentary opposition. At 65, with the last 33 years as prime minister, Hun Sen may use this period for a dynastic transition to position his sons for office after him.

The glaring absence in the election was the CNRP after its dubious ban last November by Cambodia's Supreme Court due to a supposed plot to overthrow the government with foreign assistance. CNRP leaders were also banned from politics for five years, many driven into exile and facing intimidation and harassment throughout. Without the CNRP, the poll was destined to be illegitimate. Voter intimidation combined with financial inducement was pervasive. Election monitoring from other countries, including those not known to harbour respectable electoral rule, was not seen as credible. Cambodia's own monitoring agencies were perceived as pro-government, and their independence and integrity was suspect. All told, this was simply a bogus election that yielded predictable results with alarming long-term ramifications.

The dissolved opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party's Vice President Mu Sochua, left, and Deputy Director Monovithya Kem held a press conference in Jakarta on Monday following Cambodia's general election internationally criticised as neither free nor fair. (Reuters photo)

If Hun Sen continues in power unchecked, CNRP leaders will be hard pressed to press their pro-democracy campaign from abroad. Time away and outside the country will become their most daunting challenge. The longer time passes, the more morale and resources will be exhausted. So the next three to six months are critical for the banned opposition members.

International organisations and Western democracies will have to act quickly and boldly to halt what now looks like a runaway dictatorship. The US, not the most credible and popular these days as the ostensible beacon of freedom and human rights, has imposed limited visa restrictions on the Hun Sen regime. Its bipartisan Cambodia Democracy Act of 2018 can widen the net of sanctions. The European Union (EU), with its layered structure, bureaucracy and myriad membership, needs to prioritise responses on what's just happened in Cambodia.

The time has come for both the US and EU to harden their approaches to Cambodia's dictatorship. Stiffer measures from the US and EU could target Cambodian garment and footwear sector, which constitute 80% of the country's exports. Admittedly, Cambodian workers would be adversely affected but increasing the pressure from within Cambodia may now be the only effective way ahead.

Meanwhile, Japan and Australia should be called out. The spectre of losing Southeast Asia to China haunts planners in Tokyo but they need to take a long view. Beijing has been making a lot of short-term geopolitical gains but the jury is out on what the long term foretells. Australia needs to stop supping with Cambodia's dictator for expedient benefits, such as paying for and locating Australia's unwanted migrants on Cambodian soil.

The United Nations also has a right to say something, as it facilitated Cambodia's democratic transition in 1993 after decades of war and destruction. Also weighed down by a vast bureaucracy, the UN's leadership should start treating the Hun Sen regime with similar resolve and commitment as it does with the Myanmar government's shortcomings.

Thailand's role is ironic. Normally, Hun Sen is cosy with Thai governments that are aligned with the Shinawatra clan but this time Thailand's anti-Shinawatra military government has been accommodating and forthcoming vis-à-vis its Cambodian counterpart. Dictatorships are apparently like-minded.

What the Thai military government must do is to allow refuge and safe passage for Cambodian opposition members in accordance with international law and human rights standards (for which Thailand used to be world renowned). On this point, if the Democrat Party were in power, as was the case in 2008-11, it would likely be friendlier and more receptive to Cambodia's CNRP figures. Yet senior Democrat members can still speak up for their next-door colleagues, as Asean's pro-democracy parliamentarians have done around the region.

Cambodia's democracy is not dead. It has only been denied and thwarted, not allowed to thrive. Hun Sen has done well to deliver years of economic growth and development but the opposition CNRP would likely have been able to come up with a similar economic performance while allowing greater fundamental freedoms and civil liberties. This is why Hun Sen methodically decimated the CNRP. The immediate aim for the international community should now be to squeeze as tightly as possible to see what kind of compromise and accommodation can come up to bring CNRP members back into the fray and enable Cambodia to reconcile and move ahead with legitimacy and popular participation.