The detention of an 18-year-old Saudi runaway and a Bahraini footballer are just recent examples of the Thai-style approach to international human rights issues that usually puts concerns over Thailand's bilateral ties with other nations before the rights and safety of individuals.

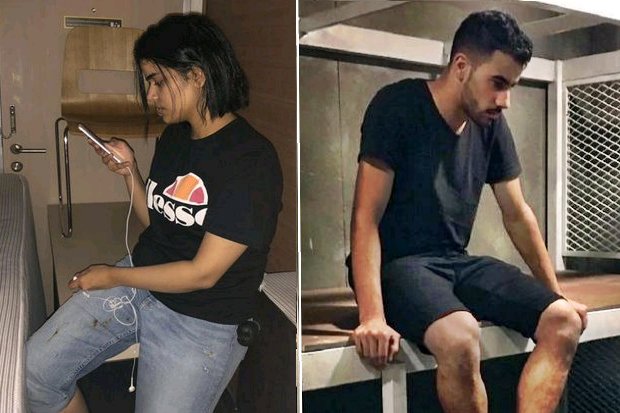

The Saudi woman, Rahaf Mohammed al-Qunun, can now live a life she wishes after the Canadian government granted her asylum. Her escape from her allegedly abusive family in Saudi Arabia almost failed when Thai immigration police stopped her on Jan 5 at Suvarnabhumi airport, planning to deport her back home.

After she had revealed her plight on social media while barricading herself in a hotel room to evade deportation, Thai officials changed their mind and allowed her to come under the care of the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Paritta Wangkiat is a columnist, Bangkok Post.

But there are many who have not been able to make their way to freedom so easily. One of them is Hakeem al-Araibi who is being detained in a Bangkok prison. He fled Bahrain in 2014 to Australia after he said he was arrested and tortured during the 2011 uprising. The Australian government granted him refugee status in 2017. But Thai immigration police arrested him on arrival at Suvarnabhumi airport last November over an Interpol red notice issued by Bahrain for vandalism -- an allegation he has denied.

In August last year, immigration police arrested almost 200 migrants from Vietnam and Cambodia, most of whom are ethnic minorities who fled religious and political persecution at home. They were charged with either illegal entry to the country or overstaying. The arrest was part of the authorities' wider campaign to crack down on illegal migrants.

Last year, Chinese dissident Wu Yuhua and her husband Yang Chong, who fled China for fear of persecution, were also arrested. Ms Wu is a supporter of disappeared Chinese rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng. Both of them are registered as UN refugees.

The Thai government's handling of many repatriation cases reflects its intention not to hurt its ties with countries such as China and Cambodia which have often asked Thailand to return fleeing dissidents.

For example, Hong Kong student activist Joshua Wong was briefly detained at Suvarnabhumi and sent back home in 2016, following a request from China. The previous year saw Thai authorities returning more than 100 Uighur Muslims to China despite their fear of being persecuted by the Chinese government.

At the request of the Cambodian government last year, Thailand deported labour activist Sam Sokha to Cambodia where she was sentenced to two years in prison for insulting a public official by throwing a shoe at a billboard featuring a photo of Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Another labour activist seeking asylum, Rath Rott Mony, was returned to Cambodia despite the threat of being tortured for his role in helping a Russian documentary producer expose sex trafficking.

A series of refugee repatriations in the past few years has led many to criticise the junta for accommodating the requests of "friendly countries" at the time it has faced international isolation. But the repatriations are not driven by the government's decision alone. Nor did they happen because Thailand has never ratified the UN Refugee Convention.

In fact, they reflect the country's traditional approaches to refugees which are often influenced by geopolitics as well as domestic concern over national security. Whenever there was an influx of refugees to the country, Thais often responded with fear and hostility arguing that welcoming one group of them could encourage more to come or that outsiders "will extract our natural resources".

In 2013, Thailand cooperated with Myanmar by returning 1,300 Rohingya refugees back home despite flaring ethnic conflicts. Back in 1993, even though the government welcomed the 14th Dalai Lama to attend the Nobel Peace laureates meeting held in Thailand, it at first was reluctant to allow him entry fearing it would hurt Thailand's relationship with China. It was the last time he was allowed entry to the country.

Even during the escalation of the second Indochina wars in the 1960s-1970s, Thai authorities allowed refugee settlements along the border but also forced repatriations of some refugees back to the battlegrounds due to the fear of communism.

With the current geopolitical context, Thailand cannot maintain its deeply-rooted sense of hostility towards refugees or its anti-globalisation perspective which views them as outsiders.

The country will always be subject to international pressure calling for fair treatment and protection for refugees. The international pressure on Thai authorities to give passage to Ms Qunun is the proof.