It has been 25 years since encryption hit the computer-internet mainstream, and it is disheartening to see just how little the issue is understood.

The current brouhaha between Apple and the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has again raised the interest level on encryption, but it has increased the steady flow of misinformation about it.

Article after story after blog entry after broadcast in the past week has misstated facts, misled readers and shown how little the public knows about a topic that can start uninformed debates at a hat-drop.

One might say, in fact, that "if everyone's an expert, then no one is". So it seemed last week, anyway, as the Apple-FBI standoff of the past year got downright testy and moved into the US federal courts.

It is disappointing.

Encryption, how it works and what the public could do about it was an issue often raised in the pages of the late Post Database weekly, carried in this newspaper. Today's columnists could quickly learn about the subject, but seem more interested in getting their political views across than in informing readers.

Thus we learned last week in these very printed and web pages that the FBI had asked Apple to "extract unencrypted user data from" an iPhone found on the cold, dead bodies of the husband-wife terrorist team who killed 14 people and wounded 22 in California.

But the FBI has done no such thing.

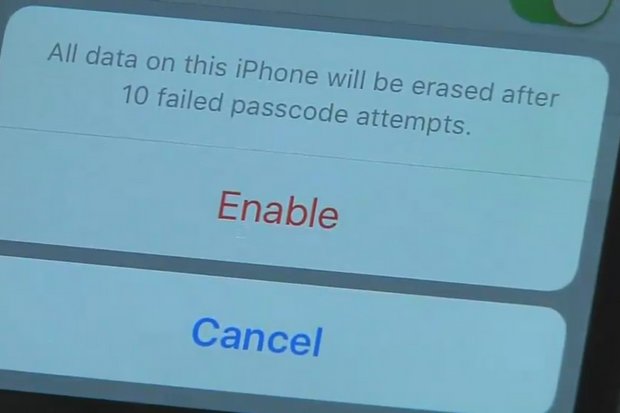

It has demanded (not asked) Apple to invent and then to insert on that phone a bit of software that does not yet exist. It wants to be able to try to crack the phone's security password by feeding it millions of possibilities with a high-speed password cracker. It cannot do that now, because Apple's iOS 8 shuts down and bricks the encryption after 10 wrong password guesses.

In addition to not even understanding the basic government demands, opinion writers have come up with such silly statements as "any encryption can be broken".

As we explained to readers of this newspaper 25 years ago, it is both impossible and uninformed to make absolute statements about computer-generated security. Who knew that plain text could be dangerous and virus-causing? Those in the field know enough never to say "never".

In any case, then and now, there is unbreakable encryption today -- both in the real and theoretical world. Virtual and real warehouses in many countries hold millions of messages the government owners would love to read, but so far cannot.

(In theory, even one-time codes, the toughest of all, can be broken. But in the real world, up to today, they will yield multiple message possibilities. An unencrypted message might say either "Begin attack at 8am" or "Cease attack at 8am". For a vastly over-simplified example.)

It seems for now that those writing about the current encryption controversies, and especially the Apple-FBI uproar, want to get across their political view about it. In essence, it will help you as a reader to know which side the writer or broadcaster falls:

One. Encryption is okay for people who want to hide stuff for some reason, but the government has the right and duty to read people's mail when it's absolutely necessary, to make us safe. If people have nothing to hide, what are they worried about?

Or, two. Privacy is the basic right of every citizen, and tops any and every government claim of "the right to know". Without doubt, crooks and bad people of every stripe use encryption, but every bit of technology since the invention of the wheel is used for both good and bad purposes, by good and bad people.

Immediately after the FBI took Apple to court, CEO Tim Cook sent email detailing why the company will fight to reject the FBI's order.

So, full disclosure. I am a Type-Two encryption person. That is at least partly informed by my knowledge that government doesn't only want data off bad guys' computers, phones, email and data in the cloud. Quite a few governments want it from me, too.

I understand that, while it is unlikely, the FBI might get useful information off the terrorist's iPhone it seized after the FBI failed completely to detect or stop the attacks in San Bernardino, California. At the same time, I know that if Apple invents and installs one software fix, one time, on one iPhone, it is handing the FBI and all US, Chinese, Russian and other spy agencies the key to every iPhone made before 2015. And to crooks and terrorists, too.

It must be clear that even if the FBI gets the fix it demands from Apple, it is only one step closer to learning what is on that terrorist's iPhone. If Syed Rizwan Farook and/or his wife Tashfeen Malik thought to put data behind Apple's encrypted wall on the iPhone, they may well have also encrypted the data itself, with very strong methods that will make it effectively uncrackable anyhow.

Or maybe they didn't. Maybe they took CEO Tim Cook at his word that Apple never would give up or cooperate to break the encryption keys. Maybe there's a treasure trove of useful anti-terrorist information; maybe there's absolutely nothing useful.

That's why governments don't want the ability to break into one terrorist's phone. They want to be able to tap, crack and view everything on every phone and computer, just in case there's something interesting there.

Reporters and commenters on this story will naturally have different, probably opposing views on the issue. If they are honest, however, they will learn the basics of the subject and not leave readers misinformed of facts.

Wanda Sloan was a columnist for the weekly Post Database section of the Bangkok Post.