Solving Thailand's deteriorating soil -- the lifeblood of agriculture -- doesn't just require commitment from policymakers and innovative tools, but also collaboration from farmers themselves.

Denuded mountains and mono-cropping, as evident in vast areas of the northern province of Nan, have brought severe soil erosion and degradation, affecting local communities.

The problems have been triggered by the felling of trees which hold soil in place and shelter areas from wind and flowing surface water. The lack of trees has contributed to a rapid decline in nutrients in the soil and thus agricultural productivity.

A similar problem has also been hitting other parts of the country.

According to the Land Development Department (LDD) under the Agriculture and Cooperatives Ministry, more than 54% of agricultural land across the country is below farming-grade quality.

Though this issue spurred farmers into action, some went in the wrong direction and found themselves compounding the problem.

Beating a vicious cycle

Amnuay Kongsorn, chief of Bua Yai sub-district in Nan's Na Noi district, took out bank loans to buy fertilisers and pesticides in the hope of boosting productivity and income. In the process, however, he accumulated debts by spending more and more money on synthetic fertilisers.

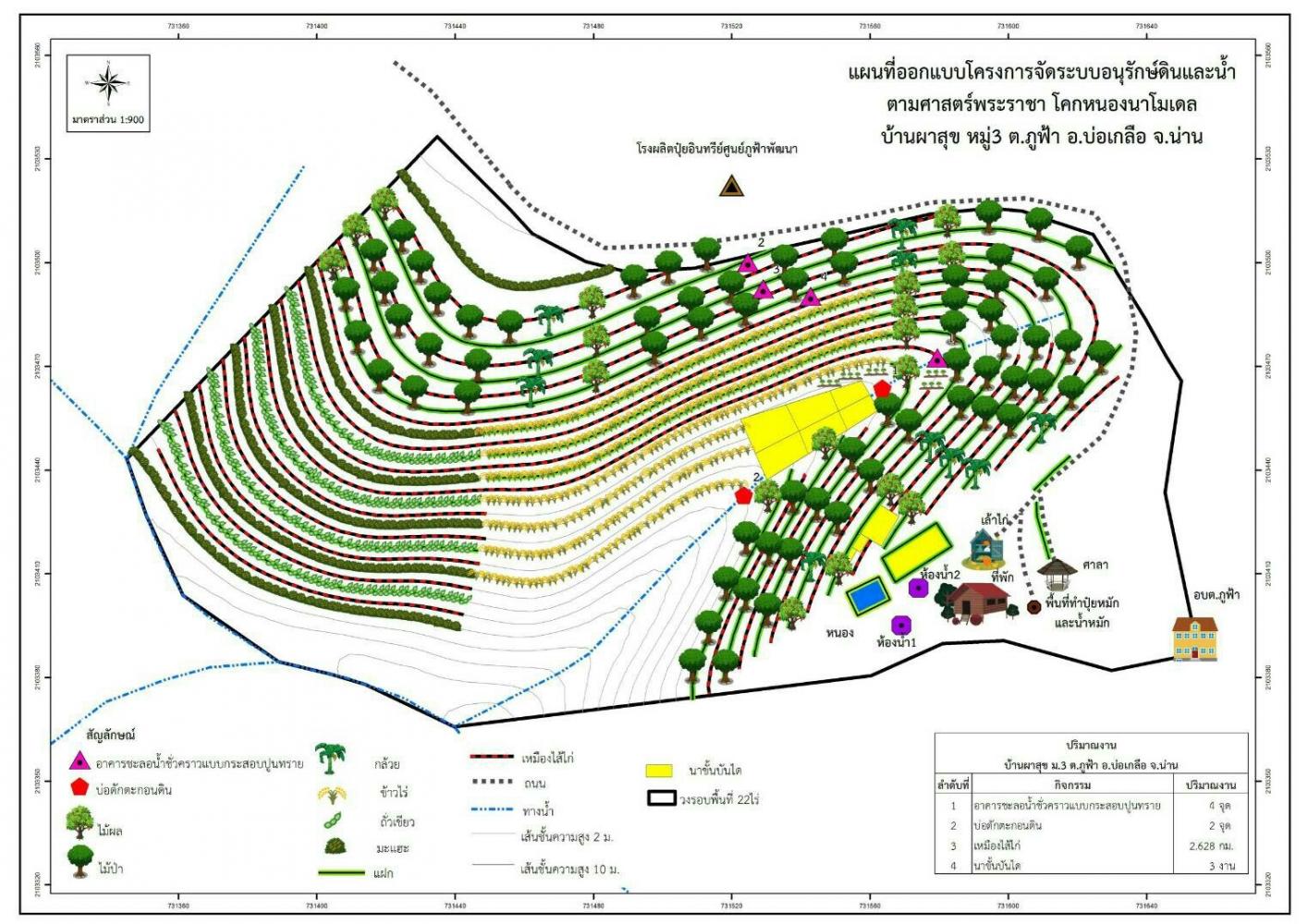

Before crops are planted, farmers and experts meet to design a farming blueprint to determine where trees should go in line with the condition of the soil.

Many farmers, including Mr Amnuay, have tried to stop using chemicals to cut the vicious cycle that drives them toward financial ruin. But they managed to go without the chemicals for only a short period. After productivity dropped, they went back to using chemicals on their farms. Their income depends on the volume of produce they fetch on the market, but prices remain low.

Apart from geographical and human-induced problems, one of the key challenges facing Thai farmers is lack of information about soil and proper technology to measure the soil's nutrients.

Consultation between locals as land users together with the government sector is crucial. The Volunteer Soil Doctor project has sprung up to meet that goal.

"To have fertile ground in agriculture, you need to understand the composition of the soil first," said Mr Amnuay, a synthetic fertiliser user-turned-volunteer "soil doctor".

Like most other farmers, Mr Amnuay was trapped in the "failure formula". He wound up with heavy debts from borrowing money to pay for farm chemicals while selling his crops at low prices. It was a predicament he thought he could not get out of.

He then joined a group of farmers called the Huk Na Noi (Loving Na Noi) which combines knowledge and best practices in non-chemical farming. The group sought assistance from government agencies, including the LDD, and other stakeholders.

The task at hand was for local villagers to acquire the right knowledge about soil and find solutions to soil problems through adopting scientific innovations while embracing the path to sustainable agriculture.

Mr Amnuay recognises that fulfilling the task is hampered by limitations as soil in the mountains where many farmers grow their crops and chemical-reliant farming practices restrict harvests and farm productivity.

He laid out the first steps to overcoming the restrictions by encouraging local residents to bring soil samples from their farms for tests.

Path to soil rehab

Soil confirmed by the tests to be of low quality requires rehabilitation. This farming practice needs reform and the "agent of change" comes from guidance handed by His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej The Great on effective soil improvement, as well as case studies and activities conducted by the Royal Project Foundation.

The foundation provides a treasure trove of knowledge about soil rehabilitation, according to Sarunnopong Chaiwattanagul, an expert on land development systems based in Nan.

Chemical-free pumpkin plants bear large fruits.

In mountainous areas of the North and the Northeast, for example, King Bhumibol recommended planting rows of vetiver grass to prevent soil erosion that destroys vital watersheds. Vetiver's web of deep roots can hold the dry, sandy soil in place, he said.

Green manure is ploughed in fields several times to improve the texture and biological factors of the sandy soil. In the South, the late king's Klaeng Din, or soil aggravation initiative has helped tackle serious soil acidity issues which had held back agricultural developments in the region.

The LDD also works with the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations to develop tools for the assessment, documentation and dissemination of such sustainable use and management of land resources including soil, water, animals and plants for long-term production, said Bunjurtluk Jintaridth, coordinator of the National Project under the Office of Research and Development of Land Management.

Finding ways to make greater use of technology and innovation in agriculture will take centre stage in the spring of this year at the FAO's Asia-Pacific Regional Conference. Thailand will be among the 46 countries represented at this high-level governing body meeting.

Success bearing fruit

Thanks to satellite technology, soil surveys, classification and mapping, farmers can learn about soil resources as well as about land use resource management in areas across the country for agricultural development and other related benefits.

As the role of public sector in influencing development is often neglected, the so-called soil doctors can fill in by enhancing villagers' capabilities through driving various activities and laying foundations for self-sufficient and sustainable land management, she said.

Soil samples are taken and tested for nutrients. The soil is rehabilitated by growing beans between other crops to add nutrients. Vetiver grass is also planted to prevent erosion.

The Bua Yai Learning Centre on Land Development in Nan is testament to the collaboration between authorities and local communities in converting land use from monocropping to integrated natural farming. Pumpkins are grown and thrive even in the sandy soil in the area of Bua Yai sub-district.

Sandy soil is permeable to water although some crops like sugarcane, cassava, and pineapple thrive in it. Mostly found in coastal areas, riverbanks and around sandstone mountains in the northeast, almost 4% of the soil in Thailand can be classified as sandy.

Local villagers learn about soil conditions and experiment with chemical-free farming of corn, pumpkins and other vegetables in demonstration land plots. Corn cobs are converted into organic, inexpensive fertiliser. Beans can be grown before corn is harvested to add nutrients to the farmland.

Mr Amnuay said it took about five years to see the full benefits of the sustainable land management project.

Now more than 1,500 rai of farm plots across tambon Bua Yai are free of chemicals. The group also regularly supplies organic vegetables and pumpkins to superstores in town as well as in Bangkok.

The Huk Na Noi members also started farming big temperate trees such as chestnuts, cacao and avocado which produce fruits that fetch high prices. They also preserve moisture and bring back nutrients and fertility to the soil.

"We've been lost for so long," Mr Amnuay said. "Now we've learned the lesson that preserving the soil is like preserving our agricultural lifeblood.

"It takes time and perseverance to bring back nutrients to our land. But we have to do it for food security -- not only for ourselves but our younger generation."