After waiting for 90 minutes at the hotel for the man who many in the Thai establishment consider the “most dangerous mind” in politics, a white Toyota Fortuner rumbles to the entrance.

Gestures of defiance: An anti-coup protester makes a variation of the three-finger salute while wearing a T-shirt reading ‘I am red’.

Following a series of email exchanges and assurances I am travelling alone and will not disclose his location, I am about to meet fugitive red-shirt leader Jakrapob Penkair, the ideologue who wants to break what he believes is the yoke of the Thai ruling elite.

“Sorry for being late,” he says with a reassuring smile as I jump into the back seat to travel to a restaurant where for two hours we discussed his plans to set up a resistance movement against the May 22 coup.

Accused of violating the lese majeste laws, Mr Jakrapob was forced to resign as a minister in May 2008 and fled to another country in 2009, where he has lived on and off for the past five years. Although he says he doesn’t want his whereabouts known, it’s common knowledge where he is.

In recent days, Mr Jakrapob has been playing a game of political “ducks and drakes”. He has been actively giving interviews to the international media on establishing a resistance movement in a foreign country, but in the same breath says there is no red-shirt gathering in neighbouring countries such as Cambodia. He has also insisted that the resistance movement has nothing to do with fugitive former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose political and financial machinery is being systematically dismantled by the military rulers to blockade any comeback.

“We ask our people not to come to neighbouring countries, no matter how struggling and desperate they are,” he says of the red-shirt masses. “Neighbouring countries have been generous all along and we can’t put them against this ruthless military regime in Thailand now.”

Pausing to feed a grey cat with spaghetti sauce from his plate, Mr Jakrapob has good reason to talk down any Thai resistance movement flowering in Cambodia as Phnom Penh comes under increasing pressure via Thai diplomatic channels.

Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen has a strong relationship with Thaksin, but Cambodia’s Foreign Affairs Ministry was last week quick to deny that Mr Jakrapob was in the country at the moment. Mr Jakrapob says there is no regrouping of red shirts in Cambodia.

He concedes the resistance movement currently consists of only a small group of people, including cabinet members from the Yingluck Shinawatra administration as well as Pheu Thai party leader Charupong Ruangsuwan.

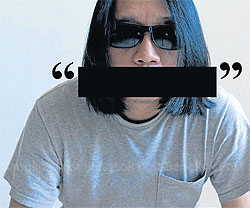

living on the lam: Former government minister and lese majeste suspect Jakrapob Penkair. Photos: Nanchanok Wongsamuth

He also denies rumours that he is married to the daughter of a Cambodian millionaire, which would have explained how he could have resided in the country for such a long time.

“I’m not the marrying type,” he told Spectrum.

During our interview, I find Mr Jakrapob urbane, well-mannered and easy-going. He has been summonsed by the junta leaders to report along with other red shirt leaders, but there’s no chance of that happening any day soon.

“Sorry I can’t send you off in person because I’m afraid I might be seen,” he said after our interview concludes, declining to get out of the car when dropping me off.

OVERSEAS RESISTANCE

When army chief Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha announced a coup on May 22, he claimed he did so to restore national security and establish sustainable democracy. Thailand’s 19th coup has brought back hope for many people who see it as an end to six months of political turmoil that inflicted huge damage on the country.

The military has systematically gone about shutting down any attempt at an organised resistance. Among their first acts was closing the borders, which shut off the route used by networks of red shirts who fled after the deadly 2010 crackdown. Red-shirt strongholds have been raided, with seized weapons caches presented to the media.

More than 500 people have been summonsed to report to the regime. Of them, 214 have been detained and 25 are facing charges. The National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) has not provided a breakdown of their political leaning. Spectrum asked the NCPO how many had failed to answer the summons, but the ruling council refused to answer.

Mr Jakrapob called the coup “arrogant and revolting”, saying that the aim of his group is to establish a democracy whereby “all aspects in society are made equal”.

“Elections are the best way to equate the power of the people to that of aristocrats,” he said, adding that the old elite is working behind the scenes in today’s crisis, and that they protect themselves from criticism by invoking the lese majeste law.

Mr Jakrapob outlined the three steps the anti-coup movement will take: to create a network both inside and outside the country, to turn political pressure into economic pressure and apply both, and to coordinate with domestic resistance groups. The location of the exiled resistance organisation has been narrowed down to four countries, and will most likely end up in Europe. He refused to say which countries.

The US, Australia and several European countries have strongly condemned the coup, and Mr Jakrapob claimed that many Thais oppose the coup but need moral and mental support.

Pruay Salty Head.

“The Thai people are waiting for us [to set up a movement], I’d bet my life on this,” he said. “There might be people who might not love Pheu Thai or Thaksin, but there are a lot of people who love human rights and democracy.”

Although he did not disclose a time frame for the process, Mr Jakrapob said he would make an official announcement to the public this month. He was unwilling to say what concrete actions the group will take, but part of it will be “human-to-human contact” rather than activities organised through social media.

Under an edict from the NCPO, unauthorised gatherings of more than five people for political purposes are banned. While they have promised to establish an interim government in August and a return to electoral democracy within 15 months, martial law has been strictly enforced on potential anti-coup rallies.

The military regime has also been quick to summons critics for questioning or detention. A core leader of the red-shirt United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), Mr Jakrapob was second on a list of 18 lese majeste suspects the NCPO issued on June 4 who were ordered to report by last Monday or face trial in a military court. Other suspects on the list are also living in exile, including Joe Wichaicommart Gordon and an online activist known by the alias “Pruay Salty Head”, who Spectrum spoke to for this article.

How likely they are to face extradition depends on their circumstances. In the case of Cambodia, Foreign Affairs Ministry spokesman Koy Kuong said the Thai military has not asked them to arrest anyone critical of the junta. Thailand and Cambodia have never signed an extradition agreement.

Cambodia has repeatedly ruled out playing host to any government-in-exile formed by ex-ministers of the ousted Yingluck government.

“I would like to reconfirm that the stance of our government is we do not allow anyone or any group to form any government in Cambodia to protest against the government of another country,” Koy Kuong told Spectrum in a telephone interview, citing an announcement by Prime Minister Hun Sen on May 27 that he would not allow the country to be used as a base for political activities.

Koy Kuong dismissed “media rumours” that there are a number of Thais living in exile in Cambodia, and that all people in Cambodia are under equal protection.

“Cambodia protects only good people; people who abide by the law and constitution of Cambodia. No one can violate any rule or law,” he said.

For its part, the NCPO has asked Thai ambassadors to expand reconciliation efforts by proactively visiting Thai communities in countries where the army has evidence of a difference in political stance.

Spokesman Werachon Sukondhapatipak said at this point, the NCPO has not yet asked foreign governments to extradite fugitives who are on the list of summonsed people.

“We are not hunting them down, but we are asking for cooperation. We are trying to tell these people to come back to Thailand to discuss things, but those who have already been charged with crimes [are not in a position to negotiate, and] need to face charges,” Col Werachon told Spectrum.

A COMMON CAUSE

At a rooftop restaurant overlooking the Mekong River, a 48-year-old man with shoulder-length hair and glasses observes those exercising below by the riverside. It is already 10pm, but many were still there in the moon light.

“I envy that the public space near the river here is for people of all classes. In Thailand, the riverside is reserved for the rich,” said Pruay, who left Thailand in December, 2011.

Pruay gained attention in 2010 when he started posting political comments under the alias “Pruay Salty Head” on the Prachatai and Fah Diew Kan (Same Sky) web forums. When he was arrested by 20 officials from the Department of Special Investigation on May 31, 2010, he was presented with a 7.5cm thick file that contained all of his posts from 2008, most of which related to the monarchy.

Pruay admitted to writing all the posts, and he was accused of taking part in a conspiracy against the monarchy. Officials confiscated his notebook computer and hard disk drive, and interrogated him for five hours before he was allowed to go home.

Joe Wichaicommart Gordon.

“They asked me who I knew, who I attended protests with and who I contacted. But I knew no one,” Pruay said. “They thought that there was someone behind all this, but when they saw the books I read they believed I was not part of any network.”

Thailand has some of the world’s harshest lese majeste laws, with penalties ranging from three to 15 years in prison for criticising the monarchy. The total number of people facing lese majese charges is unknown.

The Internet Dialogue on Law Reform (iLaw), an online project established in 2009 that supports the Thai public creating their own bills, contains comprehensive details on major cases. However, even after visiting the Technology Crime Suppression Division, the DSI and the Crime Suppression Division of the Office of the Attorney-General to ask for information, iLaw was not able to obtain enough information to be confident it had the correct figures. The most recent figures available indicate that 1,414 lese majeste cases were sent to trial between 2005 and 2012, an average of 177 per year. Judgements were handed down in 469 cases.

Although Pruay was not officially charged with violating the lese majeste law, after his interrogation officials planned to investigate further and he decided to leave the country. He knew he would not be able to express himself freely if he stayed. He is on the same list of people who have been asked to report to the military regime as Mr Jakrapob.

“I asked myself whether or not I could stop [posting critical comments]. I couldn’t,” he said. “If I left, even though I might not have any valuables with me, what is left is my freedom.”

Currently working as a freelance film director, Pruay’s Facebook page contains only one profile picture of himself. In it, he is wearing sunglasses with black tape with quotation marks covering his mouth. He openly opposes the coup, saying that it is unfair and has stripped citizens of their democratic rights.

“Many people ask me how we will fight, but I am not a leader of a network, and I don’t even want to become one. I'm just an ordinary person who has a right to freedom of expression, and I want to lead a normal life,” he said. “But I miss Thailand. Once or twice a month, I dream that I’m shooting a movie with a client. And then I get arrested.”

Another anti-coup campaigner active online, Mr Gordon also spoke to Spectrum from an undisclosed location.

A Thai-born US citizen jailed in 2011 for lese majeste offences, Mr Gordon was second-last on the list in which Mr Jakrapob and Pruay were named.

Mr Gordon was accused of creating a blog that contained a link to download Paul Handley’s The King Never Smiles, which is banned in Thailand but is widely available online in both Thai and English. Prior to this incident, Mr Gordon had lived in the US for more than 30 years and acquired citizenship. He is also alleged to have translated parts of Handley’s book and posted them online, but Mr Gordon claimed that the DSI fabricated the evidence, including the blog itself.

“I didn’t do it, and they [the DSI] couldn’t even prove it,” he said. “It ruined my life”.

He was originally sentenced to five years in jail, but judges halved the term because he pleaded guilty. After receiving a royal pardon following 14 months in prison, Mr Gordon has been travelling back and forth between the US and some Asean countries.

He agrees with Mr Jakrapob’s plan of setting up an anti-coup movement abroad and is likely to support it, but admitted the fight will be a difficult one, as the red shirts have lost many battles in the past. He advocates freedom of expression on his Facebook page, and posts anti-coup messages in Thai and English.

“I don’t understand why they think that the coup will solve the country’s problems,” he said.

LAND OF FAKE SMILES

British-born Andrew MacGregor Marshall is a former Reuters journalist who resigned in 2011 to publish a report on what he says is the royal family’s influence over politics in history.

Due to fear of being convicted of lese majeste, he is now settling down in Phnom Penh where he works as a freelance journalist and author.

Andrew MacGregor Marshall.

Marshall, whose book A Kingdom in Crisis will be published in October, said there have not been any signs that the red-shirt movement will fight or are even willing to fight.

“We are not part of some organised network. Most people are here because of their principles and because they had to leave Thailand,” the 43-year-old told Spectrum at the Metro Hassakan riverside restaurant.

“There’s this myth of an external enemy threatening Thailand and so Thais have to be unified. The myth is part of the invented narrative of the Land of Smiles.”

His view is echoed by some pro-democracy fighters in Thailand who claim the negotiating powers of the red shirts, as well as Thaksin, have weakened. These people, who claim they are not part of colour-coded politics, consider Sombat Boonngamanong to be the most powerful anti-coup campaigner.

Mr Sombat was at the forefront of anti-coup activities, and was on the first list of people summonsed by the NCPO. He is now detained at Bangkok Remand Prison.

While in hiding, he called on people to stage flash protests and demonstrations as well as to give the three-fingered gesture of defiance copied from the Hollywood movie The Hunger Games, which represents liberty, equality and brotherhood. After his arrest in Chon Buri on June 5, he was pictured making the gesture while being escorted into custody.

Because of military intervention, debate has been criminalised, while arguing or debating in itself is seen as wrong and divisive. This includes a crackdown on symbolic protests, including making the three-finger salute in public.

Academics and journalists have also been targeted. Thailand’s problems, Marshall said, must be solved by building a system based on acknowledging the truth.

“The tragedy of Thailand now is that the truth has become dangerous. Thailand cannot be a peaceful and prosperous society based on lies, and the sad thing is that many Thais have come to accept dishonesty as normal,” he said. “Reconciliation is a joke. It means don’t challenge the system, don’t debate and keep your mouth shut.”

Marshall said Thailand has been in a honeymoon period with no mass violence. But as times goes by, he expects more resistance to emerge and fears the Thai military will tend to overreact by using more violence to create more fear.

“This should be a struggle for a fair system and democracy, not for [People's Democratic Reform Committee leader] Suthep [Thaugsuban] or Thaksin. None of these elite want a fair system; they want a fair system for them,” Marshall said.

“But we haven’t been talking about what is a fair system.”

A TOUGH STRUGGLE

Almost a decade of Thailand’s politics has been dominated with the political divide between the red- and yellow-shirt political camps, with the former supporting Thaksin. It is difficult to measure the actual number of people who are against the coup, as the military has been using harsh measures to curb dissent.

After being released from detention, many prominent red shirts have announced they are washing their hands of politics altogether while the army has claimed others, including Mr Sombat, now have a better understanding of the situation.

Given the difficulties of even gauging level of opposition, many believe establishing a resistance network based overseas will be tough. Gen Ekkachai Srivilas, director of the King Prajadhipok’s Institute’s Office of Peace and Governance, was one of the few academics who agreed to speak to Spectrum on this issue, and said any movement would struggle.

“It is possible for one to be set up, but it would be difficult to reach their goal because of the NCPO’s monitoring,” he said.

With tough measures on one hand, the military regime has also been trying to win support on the other through policy decisions and attempts at achieving reform. The NCPO has been quick to overhaul a variety of projects such as those related to infrastructure, energy prices, water management projects and foreign direct investment.

“The people probably like it, because in the past political parties had enormous power. Now we are waiting to see whether the military can really solve the problem,” said Gen Ekkachai, adding that although the army came into power unfairly, they are putting efforts into creating a fairer system for the country.

But he said reconciliation is a very difficult issue that would need at least five to 10 years to solve.

“It needs a lot more [than free tickets to The Legend of King Naresuan 5] to maintain trust and acceptance,” he said, adding that any mediation role should held by a neutral figure who does not have past conflicts with any side of the political divide.

“We need to stop talking about the past and see how we can cooperate for the future.”

The message gets through to the massage parlours

Once a staunch red-shirt supporter, 43-year-old Nong ceased all political activities when he fled to Cambodia after the violence in 2007 with six friends.

Nong once worked as a masseur at the red-shirt rallies at Sanam Luang and put his skills to use in Cambodia, travelling back to Thailand only for elections and major rallies.

“The red shirts living here need to wait for new elections. Now we can’t do anything,” he told Spectrum at the massage parlour where he works.

Until six months ago Nong, who asked to be identified only by his nickname, was working at a central Phnom Penh massage parlour formerly owned by a Thai woman who heads a local red-shirt group. She has since returned to Thailand.

Several years ago, the massage parlour and restaurant would house regular red-shirt meetings, according to the current Thai owner. Since then, there have been no formal, large-scale gatherings of red shirts in Cambodia.

Nong participated in the July, 2007, red-shirt mass rally outside Privy Council president Prem Tinsulanonda’s Si Sao Thewes residence. The reds demanded his resignation from the Privy Council, claiming he was behind the 2006 military coup.

“It wasn’t right. I couldn’t bear the thought of the person I loved being bullied,” said Nong, referring to former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted in a coup d’etat on Sept 19, 2006.

Nong was so depressed he refused to listen to or watch news regarding Thailand for his first four years in Cambodia. But since the new owners of his former workplace are also red-shirt supporters, he began watching the Asia Update satellite television channel with them and soon became a regular viewer.

“But the owner’s daughter was a yellow shirt, and whenever she came from Thailand I would always wish that she would go back soon so I could watch TV,” he said.

Now Asia Update, along with many other TV stations and unlicensed community radio stations, have been shut down until further notice by Thailand’s military regime, leaving many Thais and Cambodians disappointed.

“People here can’t go to sleep without watching Asia Update. Closing it down angered Cambodians so much,” he said. “Khmers love red shirts. [Cambodia’s defence minister] Tea Banh watches Asia Update all the time.”

Nong expressed scepticism that the military regime will be successful in its international public relations offensive, a bid to blunt mounting criticism from the West.

He has recently found a new job at a massage parlour owned by the daughter of one of Cambodia’s ministers, and many of his clients are high-ranking military officers. “I overheard some high-ranking soldiers talking about the junta’s efforts to explain the situation to the international community. One of them said: ‘Who the hell is going to talk to them?’ ”

Territory of the enemy: Red shirt supporters of Thailand’s fugitive former premier Thaksin Shinawatra walk past Cambodian soldiers in Siem Reap.