As the first rays of light shone on the Bangladeshi morning, the new dawn brought hope and optimism. I got out of the van and walked down the street in Dhaka with other international journalists, the ground still wet after the rains of the previous night.

"Today is Pohela Boishakh, the first day of the Bengali New Year. We are going to the festival," said our guide. A huge crowd of locals lined up in front of Ramna Park, most in traditional attire. Men wore panjabi or fatuas while women wore saris.

"Shubho Noboborsho [Happy New Year]," said a woman dressed in red. It took me a while to get a hang of the greeting, but learning a local phrase made me feel more at home in this strange new environment.

A man approached me with paint and a brush. I nodded and let him paint my cheek. Then he handed me a red cloth and gestured for me to tie it around my head.

Walking through the park, a light breeze rustled through the trees. Squirrels ran around cracking nuts. The lake at the centre of the park was still, reflecting the orange light of the morning. All around, families could be seen having picnics.

The Bangabandhu Memorial Museum, where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh, and his family members were assassinated. Thana Boonlert

Our guide took us to the heart of the park. A choir was singing traditional songs under a banyan tree. We sat cross-legged on the grass in the shade, admiring the performance.

"Chhayanaut is a group that is devoted to preserving our cultural heritage. It is performing Tagore's song Esho He Boishakh," he said. Rabindranath Tagore, an internationally-renowned Bengali polymath, is a national hero in Bangladesh. I didn't understand a word of the song, but I still found it powerful and moving.

The Sun was high in the sky by the time we left the park. A large number of locals were already lining the streets in anticipation of the Mongal Shobhajatra. Before long, the colourful parade came into sight, with ornate floats and thousands of people carrying giant masks of various animals and gods. The crowd cheered as the procession marched past. People chanted and danced to the beat of drums, all braving the heat to celebrate the Bengali New Year.

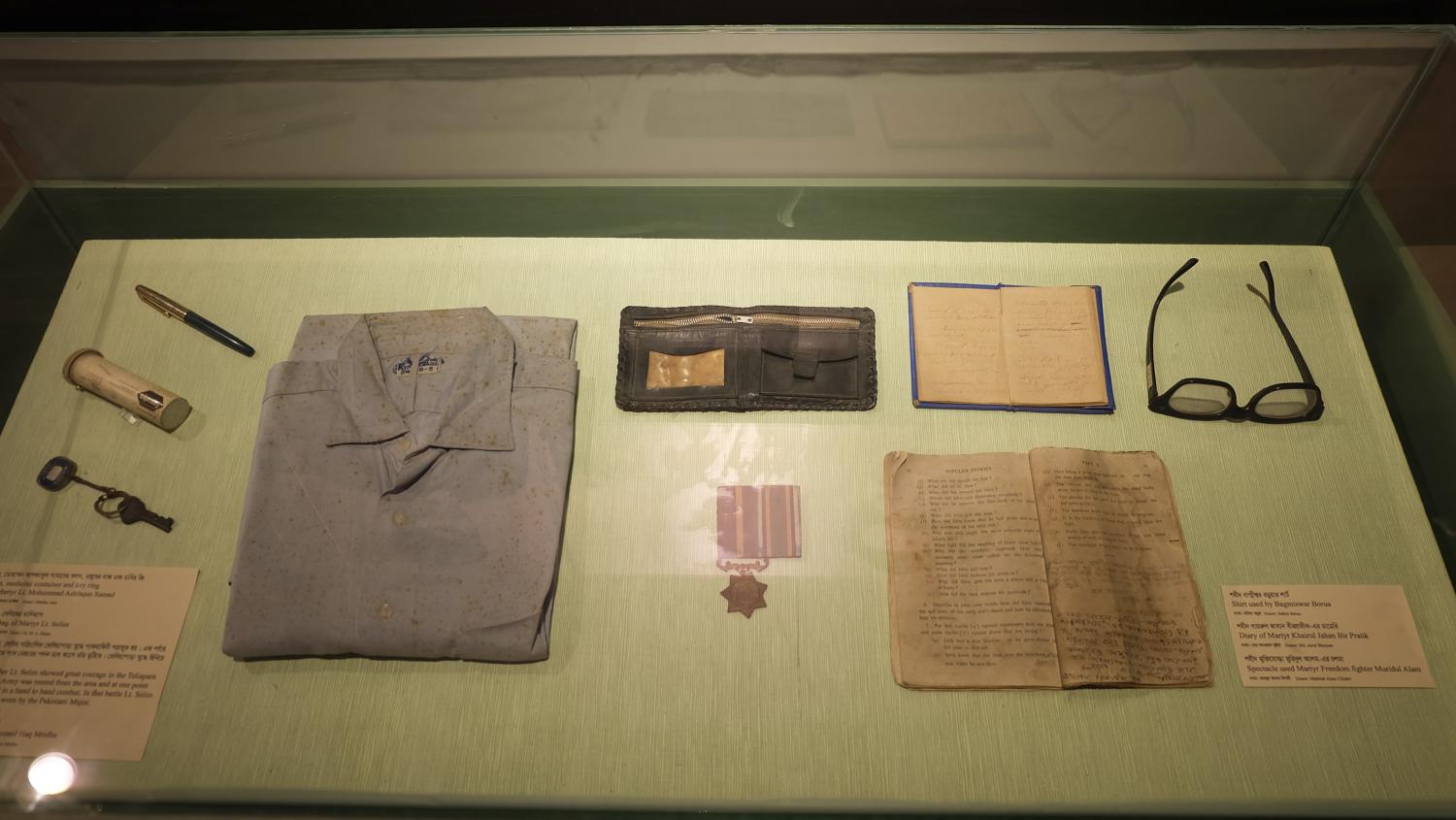

Personal items of freedom fighters who died in the Liberation War. Thana Boonlert

A local participant said the procession is the brainchild of students and teachers at Dhaka University's Faculty of Fine Arts: "They spend one-and-a-half months preparing for the parade. Many characters in the procession are based on our folklore. The festival aims to instil pride and hope for the future.

"It doesn't matter whether you are Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist. We all live in Bangladesh."

PAINFUL MEMORIES

The next day, our guide took us sightseeing, giving us a chance to see Dhaka in all its beauty and chaos. Sun-baked buildings and makeshift shacks stood in densely packed rows. Clouds of dust rose into the air whenever buses roared past. Rickshaws and tuk-tuks constantly honked their horns. Everywhere, people went about their daily lives.

We got off the van in the grounds of Dhaka University. In front of us stood a large marble-stone monument: The Shaheed Minar. The striking sculpture has a 14m-tall central column, which bends forward, toward the top. Alongside it stand four smaller columns, two on either side. The monument symbolises a mother protecting her children.

"It was built in memory of those killed in the Bengali Language Movement demonstrations [of 1952]," said our guide, recalling a time when Bangladesh was still East Pakistan.

"The government of Pakistan declared Urdu to be the main national language, despite the opposition of the Bengali-speaking people. When students and activists held a rally, the government sent police officers to crack down on them," he explained.

Our next stop was the house of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, now known as the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum. The site is a source of both pride and pain for Bangladeshis. Sheikh Mujib, the nation's founding father, was assassinated here along with most of his family in 1975.

Bangabandhu means "Friend of Bengal". This is the title by which many Bangladeshis prefer to refer to him. At the entrance of the museum, visitors are greeted with a mosaic depicting the national father. From here, we were met by the curator, who showed us around. First, he showed us the living room, where Bangabandhu would meet with politicians and intellectuals, then the study room where he spent hours reading and writing.

"It was the centre of political activities," the curator said. "Bangabandhu declared independence here [on March 26, 1971]. East Pakistan became Bangladesh. With India's help, the country fought a nine-month war and gained independence from West Pakistan [on Dec 16, 1971]."

The staircase where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was shot to death. Thana Boonlert

On the next floor, we came to a room which, at first, seemed homely and warm, with furniture neatly arranged and a television set in the corner. However, that sense of warmth is shattered when you discover what befell the household here.

The curator pointed to bullet marks and blood splodges on the floor and the wall.

"Killers broke into the house and murdered all family members," he said. The assassination took place on Aug 15, 1975, during a coup by senior military officials and political rivals.

He went to the stairwell. "Bangabandhu was shot here. It still bears bullet dents and blood marks," he said. It was reported that the killers, a group of young military officers, also ransacked his house and shot his photos.

Fortunately, Bangabandhu's two daughters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, survived the assassination because they were abroad. Ms Hasina, now 71, is currently serving her fourth term as prime minister of Bangladesh.

BLOODY WAR

The Liberation War Museum commemorates the aforementioned independence struggle against Pakistan. It is a large brutalist concrete structure in the centre of Dhaka. Its halls and galleries encompass the entire history of Bangladesh.

The museum houses a wide range of artefacts, alongside photos, newspaper articles and documents. Among the most important of these is Bangabandhu's Declaration of Independence, which calls for the people to rise up against the occupying Pakistani forces. The message was circulated all over the country via telex, telegraph and clandestine radio in the early hours of March 26, 1971.

Among the most poignant items on display are the personal items belonging to those who fought in the war. Lt Selim's diary is now brittle and yellow, his handwriting faded and almost illegible. But you can still just about make out his accounts of the military operations he participated in.

Beside this are a pair of glasses, which belonged to Muridul Alam. He was captured and hacked to death, his body was thrown into the river. When his commander went to try and retrieve the body, all he found were the glasses. According to official Bangladeshi figures, more than 3 million people were killed in the independence war, although this figure is disputed.

On the last day, we went to the National Martyr's Mausoleum in Savar, 35km north of the capital. As we walked toward the triangular monument, the nation's flag fluttered in the wind.

"It stands for the victory of our people and nation," said our guide. We laid a wreath there in honour of the martyrs, then remained silent in reflection. It was midday.

So concluded our weeklong trip to Bangladesh, a nation of warm smiling people and unbreakable spirit. It will last long in the memory.