Growing up by the beach and the South Pacific Ocean, it's impossible not to fall in love with the spectacular scenery and the sport that allows you to enjoy it the most: surfing. But Steven McArthur also loves science, biology in particular. That passion has sustained his trailblazing career as a fertility specialist for three decades.

There was no hesitation when I asked him what had kept him in the field for so long. "There's nothing more rewarding than being able to see people fulfil their dreams, or their healthy happy family," the 52-year-old scientific director of Genea tells Asia Focus via a video call from his home not far from the beach in Sydney, where another Covid lockdown has been extended to the end of September.

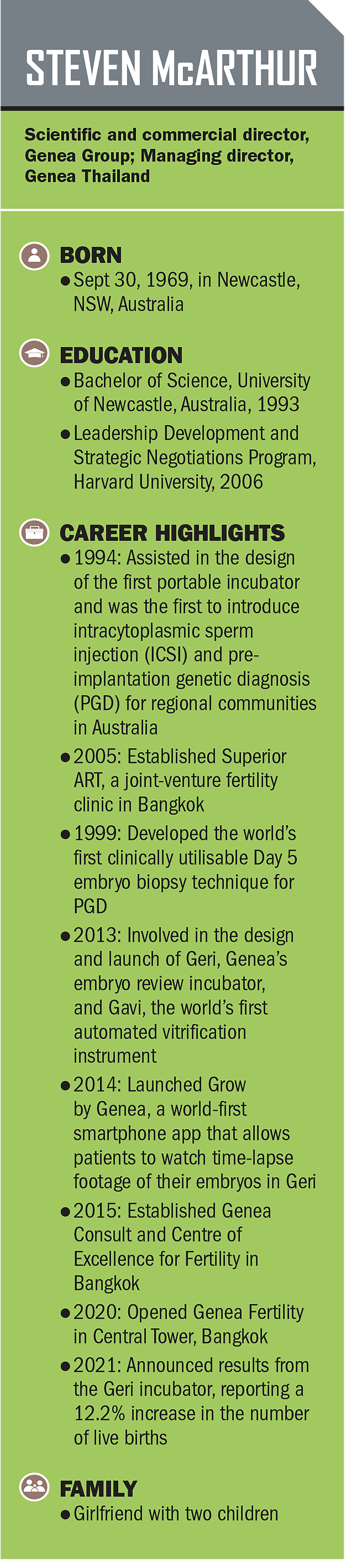

Founded as Sydney IVF in 1985, the company rebranded itself as Genea -- a Greek word for family -- in the spring of 2011. Over the past 36 years, it has become a global pioneer in the fertility sector, developing breakthrough technology and practices in assisted reproductive treatment, as well as providing consultancy to clinics.

It offers a wide range of treatments including IVF (in-vitro fertilisation), ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection), IUI (intrauterine insemination), and freezing eggs and sperm. It has offices and laboratories across major cities in Australia and also in Thailand.

Mr McArthur has built his career from the ground up, going back to the day in 1989 when he saw a job advertisement from an IVF clinic just 500 metres from his home.

"My first job in an IVF laboratory was washing test tubes," he says, jokingly calling it an "inauspicious start". After graduating from the University of Newcastle in 1993, he eventually landed a position as an embryologist at Sydney IVF.

Back then, pregnancy rates from IVF were low and the technology was still quite rudimentary -- "a baby science", as he puts it. However, he is grateful for those days as he was able to meet some leaders in the emerging field and to work on both pure and applied science.

"The field of infertility or IVF has enabled me to combine not only my love of science but also with an absolutely wonderful outcome, which is helping people have healthy families," Mr McArthur says "It's been a dream to be able to work in the field for so long."

Last year during the pandemic, Genea opened its Thailand branch in the heart of Bangkok. Despite being a new player in the country, it is no stranger to Thailand.

The involvement goes back to 1991 when Vichaiyuth Hospital approached Sydney IVF to be its business partner. Then in the late 1990s, the Jetanin Institute in Bangkok approached the company to train its scientists.

"It was actually myself and a colleague of mine, Dr Kiley de Boer, who spent quite a number of months in Bangkok training scientists in Thailand to use genetic technologies," says Mr McArthur.

In 2005, they established an IVF clinic joint venture that ended amicably in 2019 when Genea Thailand was formed.

Famous as a travel hub, Bangkok has been especially popular with medical tourists. "Bangkok makes a lot of sense. It's very central to two large areas of the globe, and so that makes it a natural place for Genea to want to operate," says Mr McArthur.

The company now has two businesses in the country. Genea Thailand is a fully functional IVF clinic, and the Centre of Excellence is a training facility. The latter hosted scientists and doctors from all over the world to train using Genea technology until Covid happened.

"The impact has been immense," Mr McArthur admits. Lockdowns and travel restrictions have barred not only local patients but international ones, particularly from the Middle East, other Southeast Asian nations, as well as Hong Kong, China and Taiwan from coming to the clinics.

The shock from an activity and revenue standpoint has also been immense, he says, as Genea is continuing to pay the full salaries of its nine local staff. "We really do have a very strong commitment to them because they signed on with us and believed in us as an organisation.

"If Covid had not happened, at this stage we would have expected to have around 40 employees working in the organisation based on the activity that we expected to see."

IN SCIENCE WE TRUST

Genea has built a worldwide reputation as an innovator, and Mr McArthur has witnessed and been part of all of the development.

The IVF process starts with a woman being injected with ovarian stimulation hormones, after which her eggs will be retrieved. The doctor combines eggs and sperm in a petri dish, allowing them to incubate. Through this process, eggs can become fertilised and develop into viable embryos.

It usually takes five or six days for a fertilised egg to form. Known as a blastocyst, it is a rapidly dividing ball of cells, the inner group of which will become the embryo and be transferred to the woman's uterus.

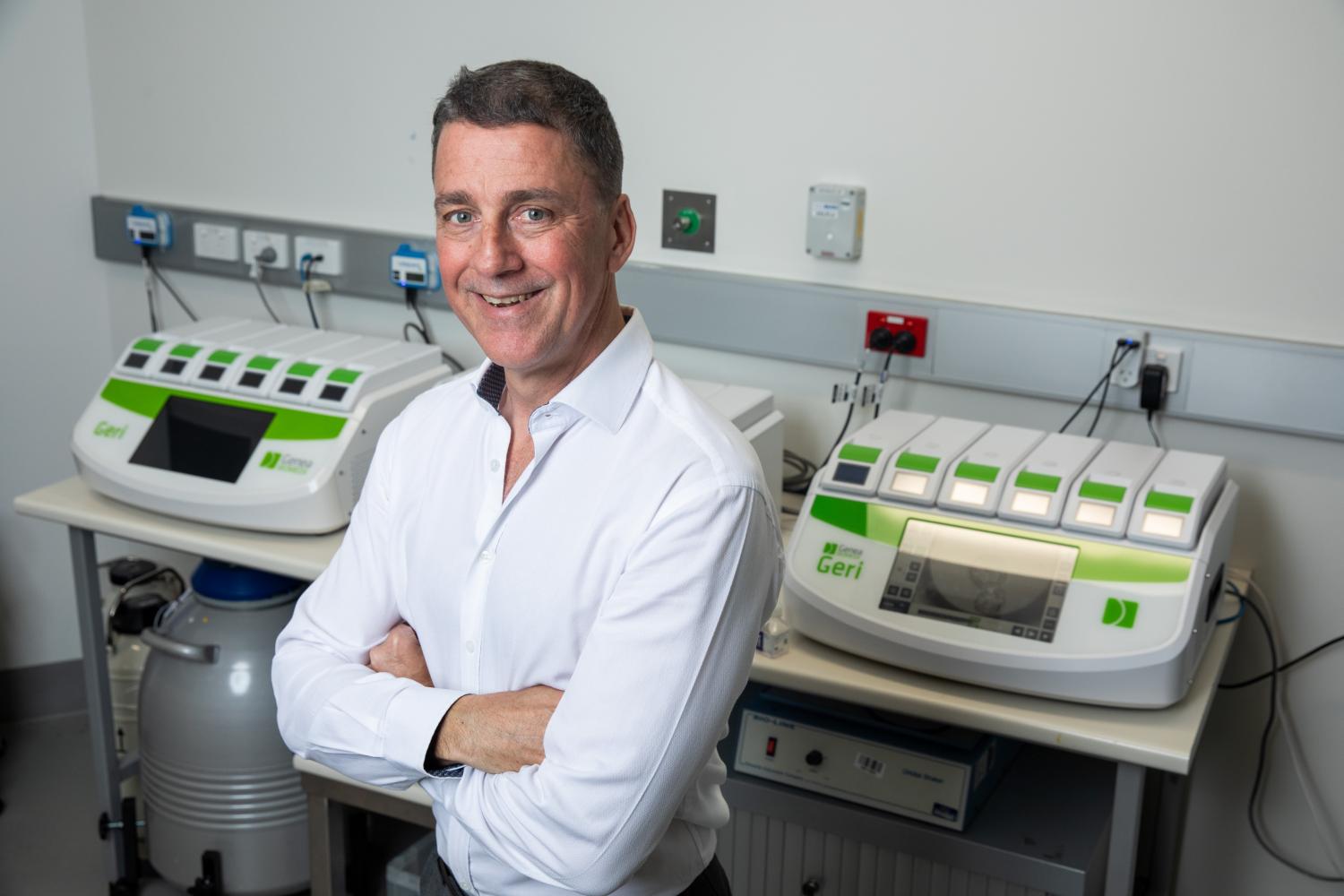

One essential tool in these complex procedures is an incubator. Despite being one of the developers of the global standard Minc incubator, Genea pushed the boundaries further with its own innovation, the Geri incubator.

Its goal was to address the biggest problem an IVF lab faces: how can the incubator replicate as closely as possible the functions of a mother's womb?

"Geri took us probably about six years to build all of the science," says Mr McArthur. The objective was "plain and simple" -- to "increase the number of healthy babies".

In other incubation systems, doctors have to take embryos in and out of an incubator, walk across the laboratory to check how they're growing under a microscope.

As soon as the embryo is out, the temperature is changing as well as the culture medium, Mr McArthur explains, "but when women fall pregnant, they don't take the embryo out every day and look at it. I know it sounds ridiculous, and it is."

"What we did when we were inventing, designing and developing Geri was saying we don't want to do that anymore. We wanted the incubator to be as close as we could make it to nature."

What makes Geri different is a built-in camera that can take photos of the embryos inside every five minutes and display them on the screen. "This allows embryos to stay in there without having to be taken out for the whole 5-6 days while they're growing.

"Every single patient has their own individual Geri incubator," he says. This advantage, optimised with Genea's Grow application that can send the videos of the embryos to the patient will enhance the IVF experience.

"It sounds a little bit scary," Mr McArthur admits, but given the Covid situation, "Grow and Geri combined allow patients to be more connected in a very personal way with their embryos."

Another crucial process, he says, is picking the embryo that gives the patients the best chance to have a healthy birth "because that's what patients come to IVF for".

Machine learning has been introduced to this process at Genea. "Artificial intelligence (AI) can actually help you predict which embryo is the best embryo to transfer," he says, adding that as Geri takes images, primarily at the blastocyst stage, an embedded algorithm will assist the scientist to pick the embryo, enhancing confidence in the process.

Though the technology is still "very young", Mr McArthur believes machine learning in the fertility field will be a big area of focus for the coming years. Although it sometimes seems like scientists have unlocked all knowledge, he says there is still a lot of mystery. "We don't know a lot about the uterus."

"We can pick an embryo really well, but then we put it back in and there's no success," he says. "We have to understand what is that gap between picking that really good embryo and no success, and if we can understand that, success rates will go up again."

OVERCOMING STIGMA

One thing many couples opting for IVF face is the stigma that lingers around infertility. Many women feel embarrassed going through the process, though in Mr McArthur's experience, "men are much less likely to talk about it than women".

"What we try to do here is to really talk about it and make people aware that this happens to people. It's a very difficult process for them as well because they're concerned not just about what their family will think, and what their friends will think. But what's more important is what the couple thinks.

"To have a dream of having a family and it doesn't work, combined with the pressure from not wanting to tell their friends makes it a really high-pressure environment for them," he says. "I can't imagine it myself, but it must be terrible.

"We try very much to personalise the service for patients. What we do is to really reduce the stress associated with it as much as we can."

In a wider sense, Genea is trying to educate the public about infertility. "Genea was involved in a whole number of educational initiatives in Australia that try educate people" from students to staff of government and private organisations that IVF is clearly part of the mainstream of medical treatment.

"The normalisation of it is talking about it," says Mr McArthur. "You have to talk about it. … Part of the difficulty for IVF patients has been that they don't think their problem happens to anyone else."

Not every patient has a successful IVF procedure and sometimes it can be emotionally painful. "What's really critical to recognise is you really have to be honest with patients from the start," he says. "It's terribly sad when you say it out loud but the reality is that IVF can't help every patient."

The data suggests that 40% of infertility is due to male infertility and 40% to female infertility, and the remaining causes are unknown.

"You have to be honest with the patient and make sure that they have informed consent. Our doctors, our nurses and our scientists play a very key role in being honest and open with patients at every step," he says.

Resources must be available for patients throughout the entire treatment. Information has to be written in easy-to-understand language.

If the procedure is not successful, the right resources and support are critical as the experience can be emotionally difficult for couples.

"We always have counselling services available for patients, but it's really important that you not force the patients to do it because everyone's different in the way that they react to negative news," says Mr McArthur.

EMPOWERED STAFF

His role as scientific director at Genea, together with his position as managing director of Genea Thailand, are more than enough to keep Mr McArthur busy. Fifteen clinics and 24 labs in those clinics are under his supervision.

More expansion could be on the horizon for Genea, which was acquired in 2018 for a reported A$300 million (US$220 million) by a consortium that includes the Hong Kong-based investment firm Aldworth Management and the Chinese health unicorn WeDoctor, which is backed by the internet colossus Tencent.

"I have ultimate responsibility both in a financial and scientific sense for all of the laboratories," says Mr McArthur. That includes 110 or 120 people around the world and at Genea Thailand. "I have a role at the board level, but also in the day-to-day management as well."

When wearing two hats and having such a big team requires a certain kind of skill. "You have to be what I would say a confidence manager," he says.

"You have to give responsibility to people. You have to let people who are working at the coalface, at the lab bench, you have to empower them to make decisions.

"There has to be a culture of accountability unquestionably because we're dealing with delicate patients with their dreams and aspirations.

"My management style is about trusting people, encouraging them to make decisions that are for the benefit not just of the patients, but of themselves in Genea."

He praises Genea for its culture of open disclosure and honesty. "No one gets in trouble at Genea for making a mistake. The trouble arises when you don't tell anyone about a mistake.

"I'm the first one to admit -- I might not have done this 30 years ago -- but today I do: I know I'm not right all the time," he says ruefully. "You have to listen and be willing to adapt and take on board the expertise and knowledge of other people."

When the demands of the job reach the point where he needs to unwind, how does Mr McArthur spend his free time? "Surfing, pretty much," he answers with a smile.

"Surfing is really good because it helps you relax. It's the greatest sport for meditation when you can sit out in the ocean and just think about things."

He started surfing at age 12 and now has as many as 14 boards. "I'm addicted," he quips. "I love the beach. I can't live too far inland. Need the salt water."

His quest for the perfect wave has taken him to many locations -- Australia, Phuket, Japan, France and Portugal, but Indonesia was his favourite. "Very dangerous, but good fun."

He also loves Thailand and it will be the first country he visits after the pandemic passes "for work and food".

"To me, Bangkok has the best food scene in the world," he says, listing tub tim krob (red rubies in coconut milk) as a favourite. "I'm dreaming of the day I can eat some tub tim krob. No Thai restaurant in Australia has it."

Another place he'll definitely swing by is Chatuchak market. "I have about 110 T-shirts, all from JJ Market. Now with Covid, I can't get any replacements."

He holds up one of them to the camera on his computer: it features a rabbit wearing sunglasses surfing atop a wave. He wears it to work. "They are so cool. You can always go and find a quirky design from a young Thai designer."