James Cagney is regarded as one of the first gangster tough guys of Hollywood. Films like The Public Enemy (1931) made him a big star and his tough-guy persona belied his background as a dancer. If you look at the opening scene to his 1932 film Taxi, you'll hear him speaking fluent Yiddish, a "High German" language that originated with Ashkenazi Jewish communities and was later fused with other German dialects, as well as the Hebrew, Aramaic and Slavic languages.

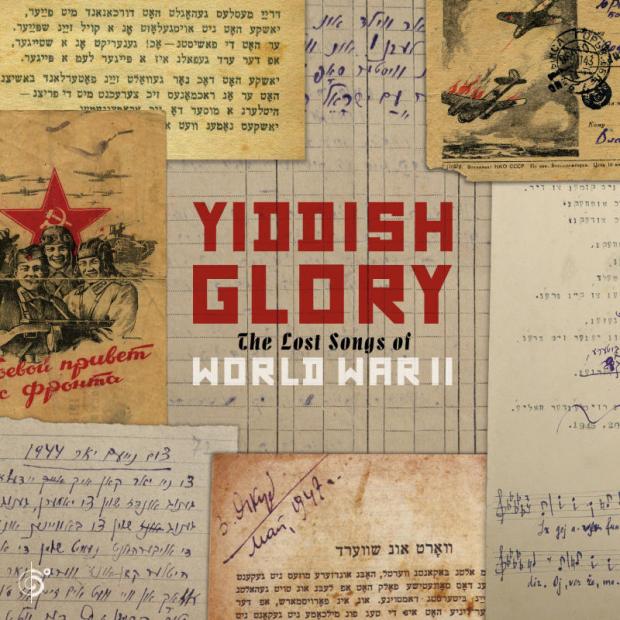

Photo courtesy of Yiddhish Glory

Yiddish was widely spoken in Jewish communities across Europe and was part of a lively popular culture in many Central and Eastern European cities. In terms of music, think of styles like klezmer, which has recently regained popularity after several revivals.

The rise of fascism and the catastrophic consequences it entailed for Jews across Europe is well-documented. We know what happened -- those who could leave did so but many were left behind and they perished as an entire culture was wiped off the surface of the planet. Those who could make it to places like the US took their culture and music with them, but what of those who stayed behind and joined the fight against fascism?

A new release, Yiddish Glory (Six Degrees, US), provides a fascinating snapshot of what folk music in the Eastern European Jewish communities was like during this dark period of history. The sleeve notes describe the context: "Created during the darkest chapter of European Jewish history, composed by Jewish Red Army soldiers, Jewish refugees, victims and survivors of Ukrainian ghettos, men, women and children, these songs tell the story of resistance, life and death under Nazi occupation of the Soviet Union."

The story of how these songs came to be recorded and performed 70 years after they were first composed makes for compelling reading. As World War II raged across Europe, a group of Soviet scholars began a project to preserve Jewish culture. Musicologists like Moisei Beregovsky led teams to record and document new Yiddish songs from across the Soviet Union. Sadly, he and many of his colleagues were arrested in one of Stalin's anti-Jewish purges, the documents sealed and tossed away. They died without knowing that their work had survived.

In the 1990s, librarians in the Ukraine found boxes with the treasure trove of Yiddish songs and they created a catalogue of the songs and poems they found. No one had performed any of the songs since 1947.

The songs are of special importance because they offer "grass roots testimonies of the German atrocities". Music was used to describe the violence and destruction; some songs were written by Red Army soldiers in the trenches (over 400,000 Jewish men and women enlisted into the Red Army), while others were written by those waiting at home or working in factories.

Many of the songs found in the Ukrainian archives did not have any music, so researcher Anna Shternshis and Dr Pavel Lion (aka Psoy Karolenko) set about creating the music from the lyrics -- something like musical archaeology. The result is a set of 17 songs, each based on what the lyrics and text suggested, which was mainly Yiddish folk tunes, popular Yiddish songs and Russian folk and popular tunes. Only one song, the lilting Kazakhstan, has an original score. Kazakhstan was one of the central Asian Soviet republics in which many European Soviet Jews sought refuge.

Once the songs had been written, producer and Afrobeat DJ Dan Rosenberg joined the project to find a group of master musicians to record the music, led by Psoy Korolenko and arranged by Russian Roma violinist Sergei Erdenko.

If you are familiar with klezmer, then some of the melodies and tunes will strike a chord, although the lyrics, sometimes drenched in blood and anger, might shock. Take Taynl's Letter To Her Husband On The Front, in which she urges her spouse to "slash them, smash them, have no mercy". Set to a popular Soviet song of the time, this version is sung beautifully by Canadian jazz singer Sophie Milman.

But for me the central song, around which the album is set, is the truly moving Babi Yar, which recounts the massacre of 33,771 Jews on Sept 29-30, 1941, near Kiev. Written by Golda Rovinskaya, the song pulls no punches with its lyrics: "Oh, blood gushed out from all sides … The earth was stained with blood."

And not all of the songs describe atrocities and sadness. Many are defiant -- they are songs of resistance. Indeed, the final track, Happy New Year 1944, is a song about victory in which the singer exhorts everyone to stop lamenting the past and look forward (by this time the Red Army had the upper hand on the Eastern front). The singer claims they can't be hurt any more by Hitler, who could only "kill us at night in our dreams". The end line is a gem, one that includes Yiddish words that have entered the English language via the musicians and artists who escaped to the US from Europe: "Hitler will be thrown in a fiery and icy hell/ And he can kiss our tuchis [ass].

The songs are currently on tour around college campuses in the US, performed by Korolenko. There are plans to reunite the musicians who recorded the songs for a tour of Europe and the US. More information can be found at www.sixdegreerecords.com

John Clewley can be contacted at clewley.john@gmail.com