Thai cinema saw a new horizon open 20 years ago up this month. On July 23, 1999, a little film called Nang Nak opened in cinemas. An adaptation of the country's most popular ghost tale about a wife who died in childbirth but stuck around as a spirit waiting for her husband to return from war, the film arrived carrying high hopes -- and exceeded all of them. Nang Nak, directed by Nonzee Nimibutr and written by Wisit Sasanatieng, unleashed an unprecedented momentum of enthusiasm and became the first Thai movie to blaze past the 100-million-baht mark at the box office.

It would eventually earn 150 million baht -- an astounding figure in 1999, when a cinema ticket cost 100 baht or less. At that time nobody thought it possible for a local production to prove such a massive hit. Nang Nak represented a watershed moment, ushering the Thai film industry into a new era of financial and creative possibilities; it restored audiences' confidence in Thai cinema after years in the doldrums, and also helped put Thai film on the world cinematic map after a successful international tour. It was, in many ways, a film that transformed Thai film forever.

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the film, Nang Nak is being re-released -- in 4K digital, not the original 35mm film -- at selected cinemas starting today. Since it was first released, you may well have caught in on television or, what a sign of the times!, on Netflix. But to see it on the big screen -- to watch that now-legendary scene when Nak dangles upside-down from the ceiling to spook a congregation of villagers -- is to remind ourselves that cinema is essentially more than just narrative or image but an experience that can remain fresh and surprising, even many years down the line.

My review of the film in 1999 was headlined "Supernatural triumph"; in retrospect, Nang Nak's phenomenal success was a combination of factors. We have to go back a little, to 1997, when Nonzee, one of several TV commercial directors who turned their interest to feature filmmaking, released his first hit 2499 Anthapan Krong Muang (Daeng Bireley And Young Gangsters). To scholars, this was actually the film that started it all: Daeng Bireley, a crime film based on real-life youth gangs in the 1950s, surprised audiences with its polished filmmaking, production quality, cinematography and art direction. Nonzee had brought with him a sophisticated skill set honed on TV commercials, and announced, tacitly, that Thai film could compete with international import. In film textbooks, Daeng Bireley (which was also a huge hit grossing 75 million baht) is regarded as the film that heralded the renaissance of Thai cinema.

Nang Nak and its 150-million bonanza cemented that upward outlook. Again, it's a film that impressed first and foremost with its craftsmanship. But more than that, the film's attitude towards the tired, much-trodden ghost story proved vital. The ghost of Nak had been in the popular imagination for decades, with at least a dozen versions of her story on film and television going back to the 1950s, all dealing with how the female ghost provoked terror in the village and affirmed the archetype of an angry woman whose wrath can't be placated even by death, before she was finally subdued by a powerful guru monk and locked up forever in a sacred clay pot.

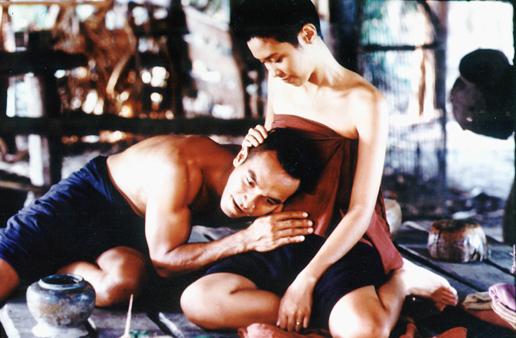

Winai Kraibutr and Sai Charoenpura revive the roles as Mak and Nak in director Nonzee Nimibutr's version of the classic ghost story Nang Nak. photo:

What Nonzee and writer Wisit did was to turn the schlock, pulpy B-movie material into a nostalgia-drenched romantic-ghost saga. In a way, they upgraded the fuzzy village horror into a semi-arthouse production. Nonzee cast two sensitive-looking actors in the roles of Nak and her husband, Mak (Inthira Charoenpura and Winai Kraibutr) and their presence was integral to the film's solemn mood and texture. The whole package worked on a psychological level too: the Tom Yum Goong financial crisis had devastated the country's economy just two years prior, yet the period saw the rise of the middle-class and along with it a need to manifest a degree of sophistication. Watching Thai films had been unfashionable; Nang Nak changed this view. Suddenly, it was a show of good taste to watch a well-made Thai film.

The tail end of the 20th century also saw the burgeoning of multiplexes in Bangkok and other major cities. New, multi-screen cinemas in large malls replaced old standalone theatres, and young people with increased purchasing power flocked to experience them as part of their "modern lifestyle". Nang Nak also had good timing on its side.

Everyone who witnessed the film's spectacular run 20 years ago remembers the euphoric anticipation it brought. Thai cinema had come of age, we believed, and nothing but a brighter future awaited. But it wasn't that simple. It's never that simple.

Nonzee Nimibutr. photo courtesy of Mono film

Twenty years on and with another Nak film marking another page of history (Banjong Pisanthanakul's Pee Mak Phrakanong, which is the same tale told from the husband's point of view, brought the house down in 2013 with a phenomenal and unrepeatable one-billion-baht revenue), the Thai film industry in general is still wading through unpredictable waters, with more flops than hits, with creativity stunted, and with audience confidence dwindling. There have been about 30 Thai films that have surpassed the 100-million-baht milestone since Nang Nak. Yet, we have to take into account higher ticket prices. Besides, these occasional hits don't reflect the reality of constant struggle that Thai filmmakers face, both in mainstream and independent circles.

By comparison, over the same 20-year stretch, South Korean cinema has risen from obscurity into a commercial and cultural juggernaut. What Nang Nak did in 1999 was show aspiring filmmakers the way, and yet the road has proven more treacherous than anyone had thought. Seeing the film again now, perhaps we can look at what it did right, and what has gone wrong along the way.