When teacher Chiratip Kaewphaisan heard about the imminent visit by a team collecting data in the northeastern province of Nakhon Phanom for a national survey on children and women, she had just one question: "Will [relevant government agencies] send an expert or a tutor to offer a special class for the students?"

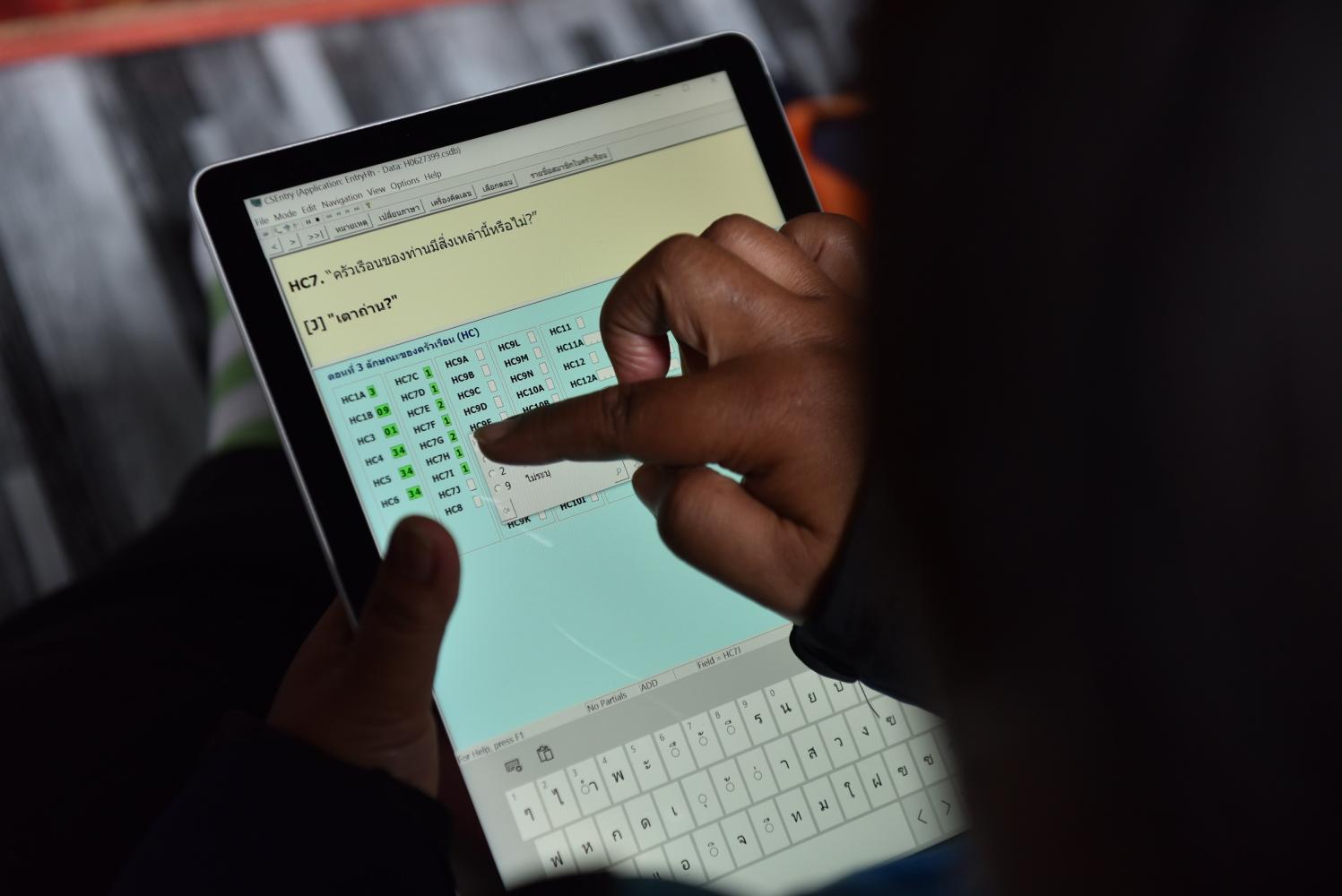

Field officers meet with families, large and small, and patiently record their responses to the survey questions on their tablets. (Photos: UNICEF/Arun Roisri)

Chiratip, who teaches Thai literacy to grade 4-6 students at Ban Ngiu Sang Kaeo School in Phon Sawan district, was right to be concerned. Around half of her fourth and fifth graders were unable to read or write properly, while five of her 21 sixth graders had inadequate literacy skills.

One of her students was to be tested in reading and numeracy skills that afternoon, as part of the data collection for Thailand's seventh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, known as MICS7 -- the country's largest survey on children and women conducted every three years by the National Statistical Office (NSO) and supported by Unicef.

The survey collects data on over 150 indicators on reproductive and maternal health, child health, nutrition and development, access to education, foundational learning skills, parental involvement and discipline, as well as early marriage, teen pregnancy and attitudes towards violence.

The targeted survey covers every corner of the nation -- from easy-to-access Ban Ngiu village in Ban Kho, an hour's drive from Muang Nakhon Phanom, to Khun Sa Nai village in the mountains of Mae Hong Son, accessible only by a two-hour drive on a winding muddy track from Chiang Mai. But distance or inaccessibility means little to the hundreds of NSO staff, who are racing against time to collect data from over 34,000 households nationwide. The survey findings are expected to be released early next year.

"The survey is important because it covers almost every key indicator that will be crucial for shaping policy recommendations on children's well-being," said Chayanit Wangdee, senior programme associate at Unicef. "The new findings will not only provide policymakers with important insight on how Covid-19 has severely impacted children, but will also inform their solutions and approaches to key challenges facing children."

Results from the previous survey in 2019 were promising in many aspects. MICS6 found that the percentage of children aged 3-5 attending early childhood development programmes continues to rise, from 60% in 2005 to 84% in 2012 and to 86% in 2019. And as many as 92% of children in northeastern provinces attend an early childhood programme, the highest in the country.

The northeastern provinces, especially Nakhon Phanom, also score high in the percentage of children entering primary school, at almost 96%. That percentage gradually drops at the elementary and high school levels. Worryingly though, and reflecting teacher Chiratip's concerns, the reading skills of students aged seven-14 in Nakhon Phanom are lower than the national average.

"I can't figure out why some of my students can't read or write properly," said Chiratip, dismissing the claim made by some grandparents in the village that the lessons were too difficult for their children. "If the exercises were too difficult, how could other students in my class complete their homework?"

The ability to read and understand a simple text is one of the most fundamental skills a child can learn. Acquiring literacy in the early grades is crucial because doing so becomes more difficult in later grades, particularly for those who are lagging behind.

Tiam Sankhumpol, a father of two living in Ban Kho, empathises with the children who are living with their grandparents and whose parents are away working in big cities.

"Sometimes I couldn't answer those homework questions either. So how could their [illiterate] grandparents help?" said Tiam, adding that he was one of the few parents in the village holding a bachelor's degree.

Below Lawan Junyanun of the Mae Hong Son branch of the National Statistical Office, commutes to remote villages on a motorcycle to collect MICS7 data.

Ratchadapa Chotchuen, a science teacher at nearby Ban Na Tao School, also noticed that many of her students who are unable to keep up in class come from families where parental support is minimal.

"Support from teachers and caregivers is essential to helping a child learn effectively."

Many of her students are living with their grandparents, most of whom can barely write their name and are unable to help with homework. Prolonged school closure during the pandemic had made it even harder for them over the past two years. Without sufficient devices and teacher consultations, many were unable to keep up with their lessons. Children from Tak, Nakhon Ratchasima, Narathiwat, Pattani and Yala faced the greatest difficulties in accessing equipment for online learning.

The statistics from MICS would seem to bear this out. The percentage of children living with neither their mother nor father has kept rising, from 18% in 2005 to 21% in 2012 and to 22% in 2019. The latest survey found that one in five children live with neither parent, although alive, with the figure rising to 35% in the northeastern provinces.

This absence of parents has resulted in low parental involvement in children's learning in Nakhon Phanom. Mothers' involvement is as low as 43%, compared to the national average of 62%, but still better than that of fathers at 21.8%, compared to the national average of 33.9%. Parental involvement, such as telling stories or playing with a child, is critical for supporting and caring for young children so that they can develop to their full potential.

In rural Mae Hong Son, lack of knowledge about nutrition is also a worry. Worachat Kongrattanasat, an assistant village headman of Khun Sa Nai, said that while villagers are able to make ends meet, many lack knowledge about nutrition, so they often eat whatever is available. The isolated location of the village means a limited choice of proteins, and villagers' beliefs prohibit them from eating pork and some types of fish, making the choices for protein-rich food even smaller.

Right An officer measures the height of a three-year-old boy as a part of the data collection on child nutrition.

"Many parents have never been taught how to find alternatives to protein," said Worachat, adding that although children might learn about nutrition or consume milk at school, they often have no say in what is served to them at mealtime at home.

His concerns were reflected in the 2019 survey, which revealed that 26.5% of children in Mae Hong Son are stunted -- a condition that arises from inadequate nutrition over a long period of time and that can cause a child to be short for their age or harm their long-term brain development. This stunting rate in Mae Hong Son is double the national average of 13.3%. The survey also found that stunting is more common among children from the poorest families.

"The provincial findings help identify children's needs in certain regions," said Nonglak Ngowiwatchai, director of the Social Statistic Division of the NSO. "For example, some children are much shorter or have a lower weight than their peers in the rest of the country, while some might be learning slower than those in other regions. The data will be used by the relevant agencies to inform policies in the future."

Approaching families for the survey has always been challenging, but the recent pandemic has made data collection for MICS7 even more difficult, Nonglak added. In addition to carrying tablets and tools to collect data, such as a digital balance and height scale -- staff must also protect themselves and others from Covid-19 by wearing masks and gloves and carrying disinfectant spray to clean any tools before and after use.

In 2022, Unicef provided around 7.74 million baht, or around 35% of the total cost of the new survey, to help the NSO collect quality data at the provincial level, specifically in the 10 poorest provinces. To support staff in their fieldwork, the budget was also used for providing tablets as well as face masks, antigen test kits and hygiene supplies.

"This new survey, MICS7, will provide an overview of the progress made for children's well-being over the past years, along with the key challenges and disparities facing children in the most vulnerable and disadvantaged provinces and communities. The survey findings aim to help policymakers shape better policies so that no child is left behind and can achieve their full potential," said Chayanit.

Keeping calm, Lawan Junyanun politely asks to see the ID cards of the family in whose house she is currently sitting. Lawan has so far been unable to fill out the names and dates of birth of each family member on her tablet. A few minutes later, the house registration is brought to her to complete the basic data section of the online forms.

While the work can be frustrating, the 45-year-old field officer, who has been with the Mae Hong Son branch of the National Statistical Office (NSO) for 24 years, shows great patience when filling out the 10 names of the extended family. Nor does she mind spending a further hour posing questions to each family member.

A young mother stands on a weighing scale with her child.

Lawan was recently collecting data from a household in Ban Khun Sa Nai Village of Pai district for Thailand's seventh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey or MICS7 — the country's largest survey on children and women conducted every three years by the NSO with support from Unicef.

The survey compiles data on more than 150 indicators covering reproductive and maternal health, child health, nutrition, and development, access to education, foundational learning skills, parental involvement and discipline as well as early marriage, teen pregnancy and attitudes towards violence from over 34,000 households across Thailand. Lawan's task is to collect all this data by asking questions, double-checking the living conditions to make sure they are in line with the information given, and measuring the height and weight of children under five in sample households.

Lawan's work has taken her to households in Muang district, which can be easily accessed on foot. It has also taken her to hard-to-reach villages, like Ban Khun Sa Nai, which can take up to two-and-a-half hours each way by motorcycle or a four-wheel drive through a winding muddy track.

A household can be a family of three or an extended family of 15. If any of them are absent, Lawan must return until she has the complete data on the household. That means asking the village head to provide accommodation for a few days.

Staff from the Nakhon Phanom branch of the National Statistical Office and Unicef reach Ban Ngiu village.

Recently, Unicef and the NSO teams from Bangkok made a field visit to Mae Hong Son and Chiang Mai to monitor the fieldwork of staff. Lawan was delighted to accompany them in their vehicle, as travelling to the village from her home in Muang Mae Hong Son by motorcycle can be arduous.

Staff like Lawan must follow global MICS guidelines and protocols by Unicef, which have been adapted to the Thai context by NSO, to ensure consistency and quality in data collection. Daily challenges for officers vary, such as extreme weather, difficult routes, unwelcoming or unavailable homeowners and unco-operative children.

Incidences of scams have made homeowners more suspicious of uninvited guests, making it harder for officers to reach some households. In certain areas of Bangkok where households can be located in a condo block, security makes access even more difficult.

"Despite our uniform, some homeowners simply shut the door in our face because they're afraid we are trying to pull a scam," says Lawan.

That problem is more easily overcome in villages, where staff can make appointments with families through the village head. But even here, the path isn't always so smooth.

While it might be easier to enter a home in a village, collecting data isn't. For example, dealing with young children to get an accurate height can be a challenge. Most babies become upset at being forced to lie down on their backs on a height measurement scale. Many cry so much that the process must be halted, meaning longer working hours for Lawan. Or many questions about children often must be addressed to the mother, which means Lawan must make another visit if the mother is absent.

Enumerators collect data on over 150 indicators on the health, nutrition, development, education and protection of children and women.

"I have no other choice but to wait for the baby or toddler to calm down for the process to restart or for the mother to return home," said Lawan, who often finds herself having to return to a village as, despite making appointments, some family members can be absent and the surveys are thus incomplete. "An officer can drop a household from the survey only if they failed to reach it after three visits. But we always aim to get it done."

An 8-year-old girl is being tested on her reading and numeracy skills, which are one of the most crucial and fundamental skills a child can learn.