Under authoritarian rule, truths are silenced, censored and mutilated. Yet, many people find ways to tell their stories. It is an irony, though, that a repressive regime is a precondition of creative resistance.

With his background in history, Anon Chawalawan is collecting bits and pieces of ephemeral memorabilia -- from posters and daily newspapers to revelation letters -- in order to cushion the blow of public amnesia.

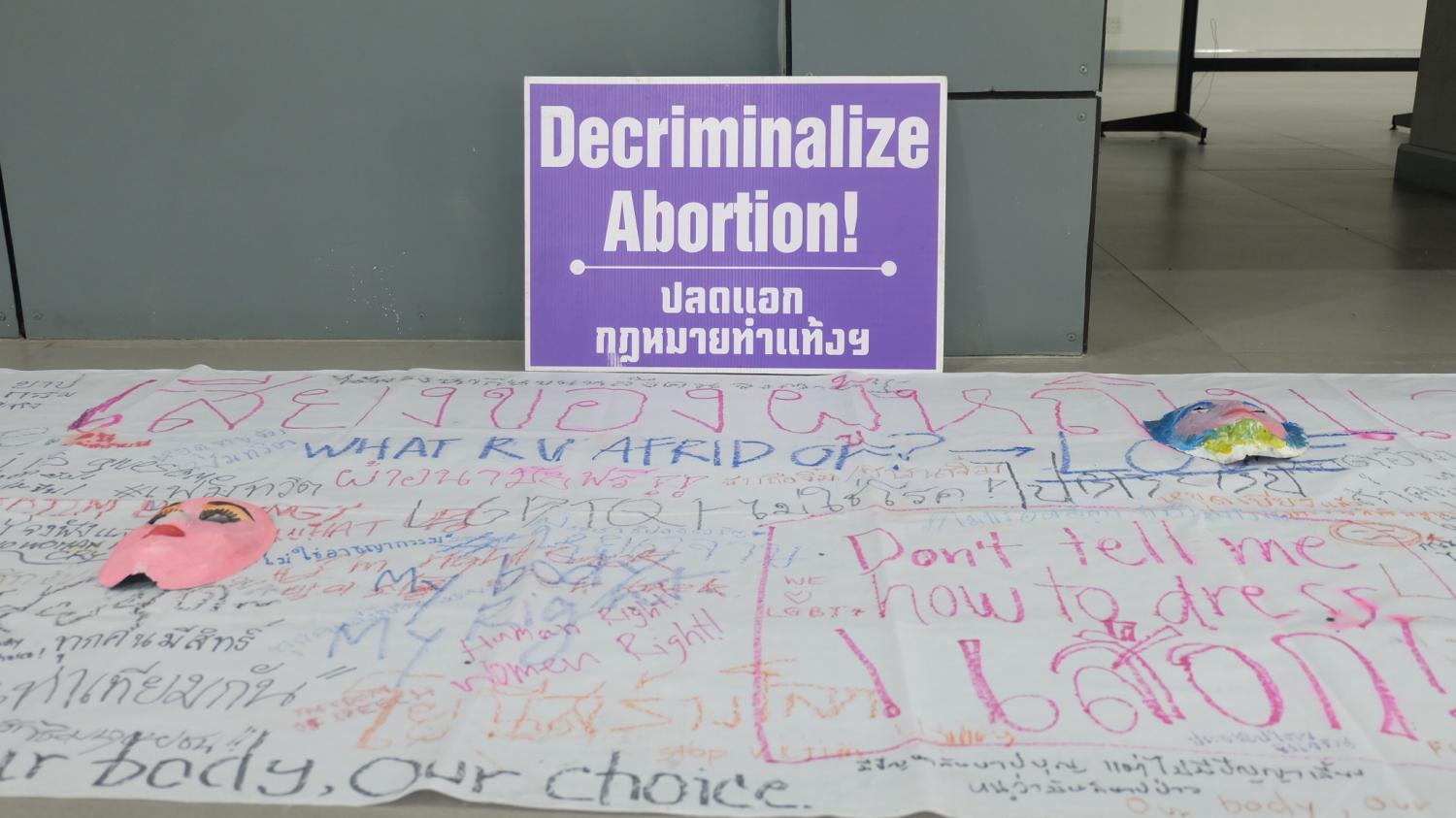

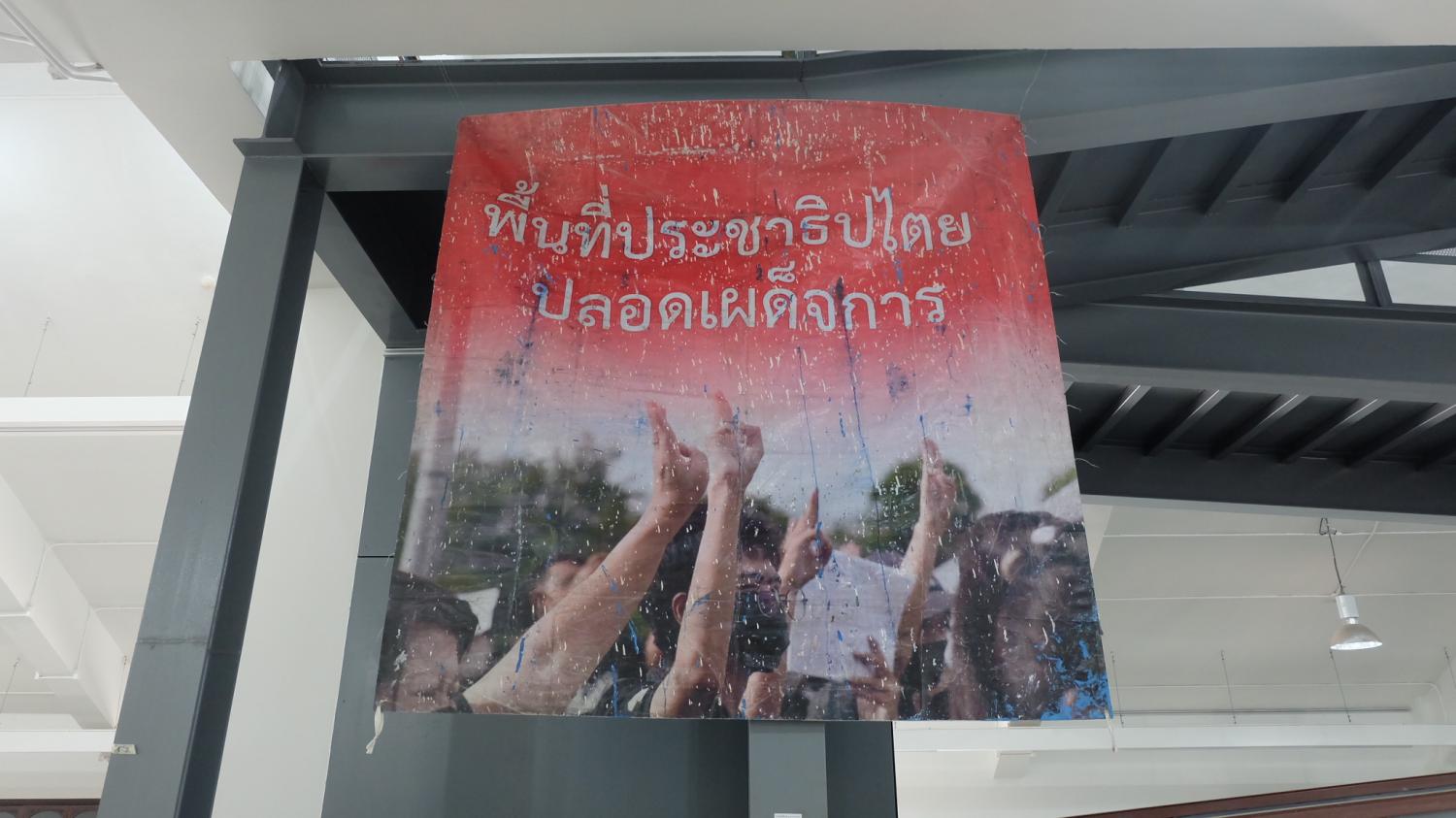

Shouting (figuratively) are banners with vocal messages, for example "Want an election" and "People are the highest power". Nearby, a white cloth vents anger over the infringement of women's rights. A vinyl strip that declares "A democracy area, free of dictatorship" hovers above rubber ducks. It appeared at a rally in front of parliament on Nov 17, 2020, while MPs and senators were reviewing charter amendment drafts.

"It is my most favourite item in the exhibition," said Anon, founder of the Museum of Popular History. "They rejected the petition that received around 100,000 signatures [and other drafts]. Supporters were blocked and dispersed. I saw this banner on a van with a broken window. Rubber ducks were pierced and deflated. It was full of violence, but protesters refused to give up. It is their right to stay there."

It was the same day when rubber ducks became "a hero", he recalled, after demonstrators used them to ward off water and tear gas. At first, they just brought them as a symbolic gesture in case some lawmakers fled parliament by boat. Since then, yellow ducks have been a symbol of the pro-democracy movement. Cuddly creatures appear in a wide range of cultural expressions, from books to calendars.

Currently on view is his collection of memorabilia at the Thammasat Museum of Anthropology. Located in a small room at the university's museum in Rangsit, the interactive exhibition gathers evidence of resistance into a chronicle of key protests in contemporary Thai politics, from rival demonstrations between yellow- and red-shirted supporters to the recent youth-led pro-democracy movement.

Some of the exhibition's wide range of protest art. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

"I am trying to make sure that this exhibition represents all shades of political belief. I collected items myself during the Ratsadon Movement, but many people also shared their own with me. I am impressed with the newspaper that covered the dispersal of protesters in 2010. An officer is bending down near a banner in which 'live firing zone' is mistranslated as 'life firing zone'. When I grabbed the real newspaper, it was more powerful than seeing it on the screen," he said.

The exhibition itself is divided into various zones. In the corner, visitors find protest banners and mock-ups. Some scenes depict protesters taking to the streets to demand change. Others show some people just making ends meet from protests, for example street food vendors, who earned the nickname "Central Intelligence Agency" because they reached protest sites before police and protesters. Nearby, there is a starter pack for amateur demonstrators.

In the centre of the room is a display showing evidence of state-sponsored violence. Blood-stained shirts of Payu Boonsophon and Sirawith Seritiwat, both of whom were attacked by riot officers and thugs in different protests, are placed together over newspapers and rubber bullets. There's assorted protective gear including shields, helmets and, yes, rubber ducks. Other miscellaneous items include a loudspeaker and first-aid kit.

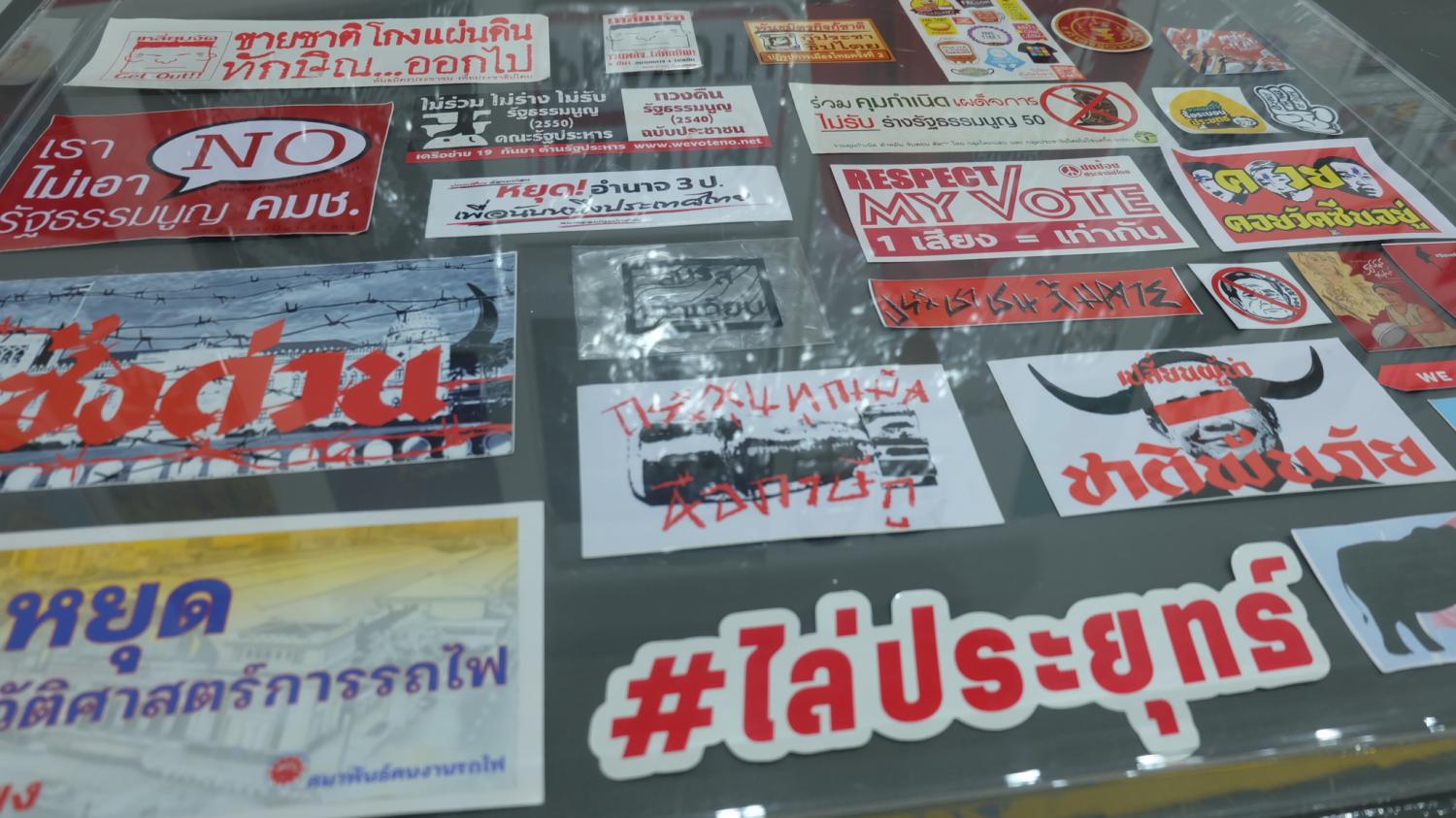

"Protests are often portrayed in a violent manner, but actually are involved with creative expression," said Anon, pointing to protest artworks and T-shirts. In the corner is a pile of CDs and cassette tapes, which visitors can play to enhance their experience. On the table are stickers, clappers, masks, dolls and headbands. His collection also includes letters and protest statements.

"Most importantly, demonstrators come from across the political spectrum, but use similar objects to protest, which means they have a lot more in common. The question is whether their feud necessarily entails violence," he said.

As a history student, Anon wondered why the history of less prominent protesters is rarely mentioned in textbooks or exhibitions. At one point he worked for an institution in the Netherlands that accumulated social movement-related objects. Later he joined the We Walk campaign, marching from Bangkok to Khon Kaen, and afterward he was inspired to start the Museum of Popular History in 2018.

Anon Chawalawan, founder of the Museum of Popular History, with a 'biscuit for democracy'. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

"Participants soaked their feet with dye and stepped on cloth. It produced a record of a moment in which they faced hardship together. However, I did not think it was right for me at the time, nor later, to ask that they give me something for my own records. It was their chronicle of politics. However, with support from other collectors I have been able to make the protesters' involvement part of this exhibition," he said.

Assoc Prof Prajak Kongkirati, a lecturer at Thammasat University's Faculty of Political Science, said contemporary history can disappear if nobody keeps a record of it. A poster of the protest against the invasion of Iraq at the exhibition confirmed that he did join a demonstration at Lumpini Park. In fact he had written an article about the demonstration solely from memory because he was unable to find any reference material on the internet or in any newspaper.

"I doubted whether it took place because my friends and reporters couldn't remember it. But I didn't make it up [the article]. I am very happy to find the poster here," he said.

Assoc Prof Yukti Mukdawijitra, lecturer at Thammasat University's Faculty of Sociology and Anthropology, said what Anon is collecting is "the prehistory of commoners". Most of them do not have history because there is no written record of them. On the other hand, their stories appear and meanings emerge in objects of everyday use.

The Museum of Popular History does not have an operation site. Anon keeps objects in his friend's room and exhibits them on a per-project basis. When it comes to the process of collecting, he gathers whatever he can find on the ground. The actual ground. For example, he took a bus to Din Daeng to collect what was left in the road on the morning after a recent clash.

Having worked on his project for four years, he feels passionate and committed but worries about his health. "If I am st ill fit, I will continue. I hope that when I bow out, the museum will live on. If you have history in the wardrobe, you can share it with us. I can't work alone," he said.

The exhibition "Evidences Of Resistance" is held from Feb 20 to May 26 in Room 112 at the Thammasat Museum of Anthropology at Thammasat University's Rangsit campus in Pathum Thani. Open on weekdays from 9.30am to 3.30pm.

Follow the exhibition at facebook.com/commonmuze?_rdc=1&_rdr.

A banner calls for reproductive rights. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

These items call for uprooting the now-defunct National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

Visitors can find banners, mock-ups, and a starter pack for amateur demonstrators. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

Clappers and paraphernalia have been symbols of many protests. For example, yellow-shirted supporters used hand clappers. In response, red-shirted demonstrators came up with foot clappers. Meanwhile, young protesters hijacked them and created three-finger clappers. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

Protest stickers. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

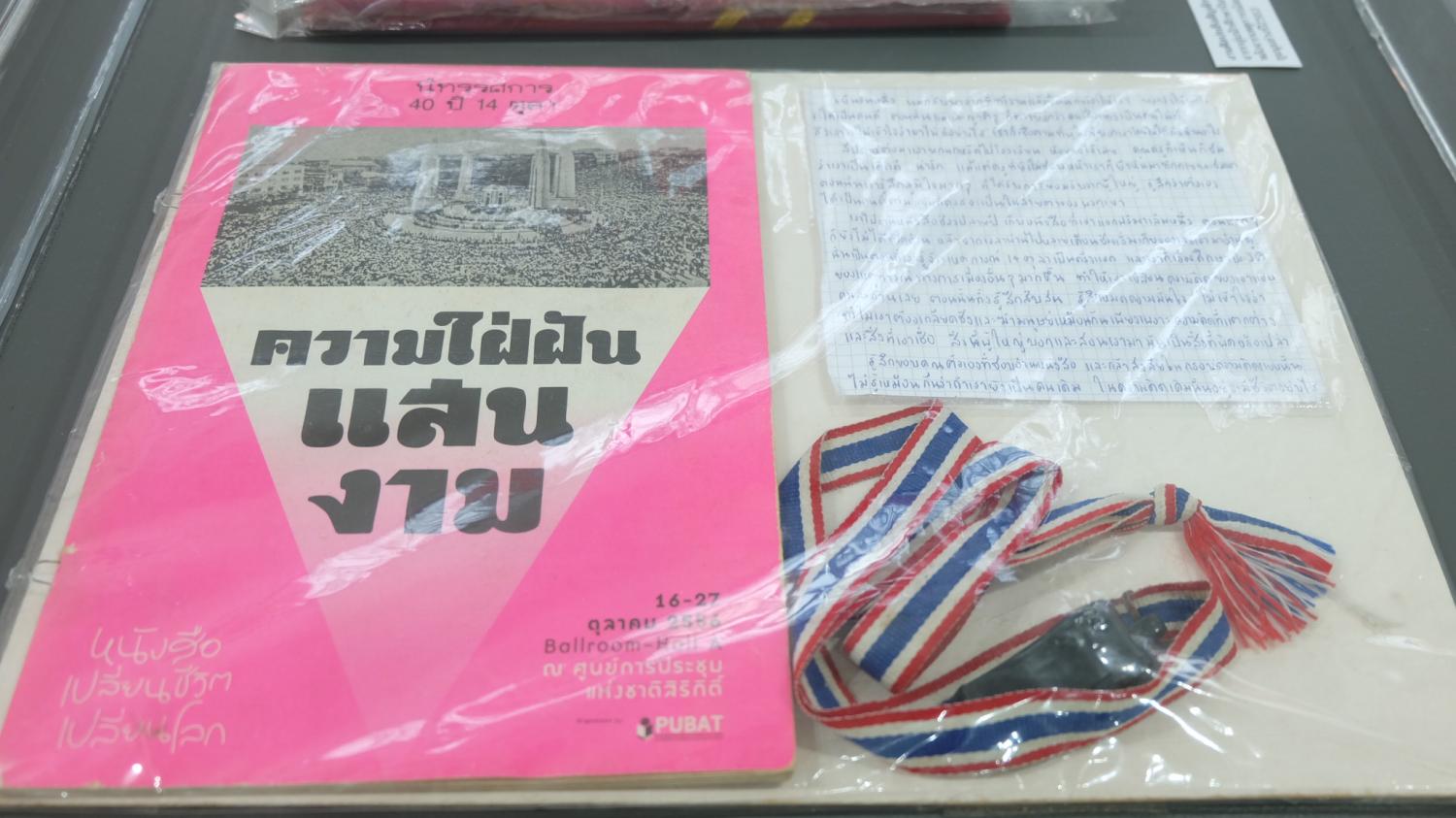

In a revelation letter, a writer says her mother gave her a whistle and asks her to carry it to be a good person. At school, teachers complimented her. Later, she received a free book in pink cover titled "Beautiful Dream". After reading it, she learned more about political events and felt awakened. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

A vinyl banner reads 'A democracy area, free of dictatorship'. It appeared at a rally in front of parliament in 2020. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)

Rubber ducks and posters calling for the release of political prisoners. (Photo: Thana Boonlert)