Chainat Raikratok can vividly recall the day he left the jungle on Feb 17, 1983. The 63-year-old former communist fighter, along with several dozens of ex-soldiers from Zone 207 in Prachin Buri province, decided to put behind their guerrilla fighting days for good.

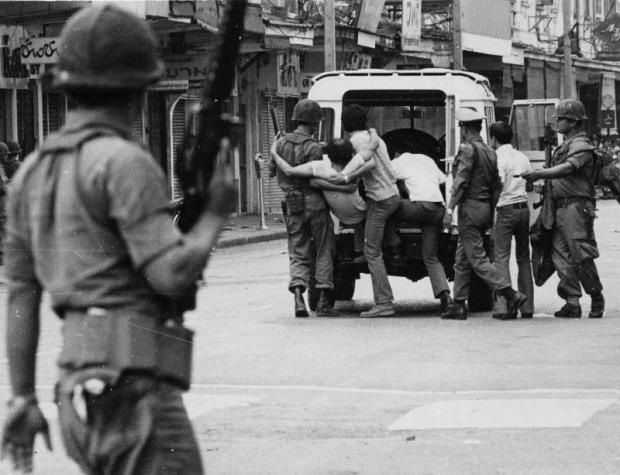

Taking up arms: CPT members stationed in the jungle of Thailand. The Thai jungle provided a hidden space to retreat from the watchful eye of the government.

"I was the last person who left the camp," Mr Chainat said. "It was a difficult decision to leave but it was good for us comrades. Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda's government promised to help us resettle and not prosecute us."

Mr Chainat spent 10 years in the red zone along the Thai-Cambodia border. However, the story of how he, as a boy born into a poor family, became a communist insurgent dates back to Oct 14, 1973.

Mr Chainat, a Korat native, arrived in Bangkok to work a series of odd jobs after finishing his Grade 4 education. In the capital city, he met several student activists who encouraged him to join political rallies to demand more rights and freedom under the government of then-prime minister Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn.

Widespread discontent was fuelled in part by economic woes stemming from high oil prices. Mr Chainat said that people at the grassroots level felt that they were being taken advantage of by capitalists and oppressed by the dictatorial regime.

These were the conditions that led Mr Chainat to join the CPT. "Without oppression, there would be no revolution," he explained.

The momentum of the communist movement reached a peak on Oct 14, 1973, when Mr Chainat joined friends on Ratchadamnoen Avenue to rally.

"The students arrived bare-handed," he said.

Yet as the day crept towards evening, soldiers begun firing shots at protesters after hearing the sound of firecrackers go off from the mass of rallying activists.

Along with 30 other students, Mr Chainat fled the scene straightaway.

"If we hadn't fled like that, we might not have survived," he said.

After the rally, he and his friends went into hiding in Korat.

After a month, representatives from the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) approached him at his home, and persuaded him to officially join the party.

His interest in joining the CPT came well before that moment when he was approached.

"Every member of the party had a different reason for joining," he said. "Some wanted to demand freedom from the dictatorship regime. Some wanted the opportunity to be educated because the party members told us that we would have equal opportunities to study."

Mr Chainat said they looked up to China and Laos as their political models.

Each party member was dispatched to a different post. Mr Chainat was sent to a military base along the Thai-Cambodia border, while some of his student friends were sent directly to Cambodia and Laos. After a while, Mr Chainat moved to Laos to enroll in a military school that taught politics in Champasak province for two years. He then proceeded to spend two years and a half studying modern medicine and acupuncture in China.

His stint in China was followed by additional military training in Hanoi as the CPT required a commander for a base camp at the Thai-Cambodia border.

After two years in Hanoi, Mr Chainat was sent back to lead Zone 207 in Prachin Buri. However, by that time, 1979, Mr Chainat was unable to enter Thailand through Cambodia due to ongoing fighting with neighbouring Vietnam. He was forced to sneak into Thailand through Ubon Ratchathani. After hiding in Bangkok for a month, he was finally sent to assume his new post at the Prachin Buri base.

At the base, he oversaw a clinic for communist fighters based in the jungle, run by seven doctors.

"It was like living in any countryside community," he said. "Communists made for the most ordinary villagers."

He became known as Comrade Viset. "Everyone had to conceal their identity so we all had an alias to protect our family back home if we were caught."

Later on, he was forced to change his name to Comrade Chainat as he found out there was another Comrade Viset who came before him.

Mr Chainat lived in area home to 20,000 families. The area served as a production base for agricultural producers at the front line in nearby provinces. He came to know CPT Members who would go on to become politicians like Karun Sai-Ngam and Adisorn Piengkes, who were responsible for the CPT's communication strategies.

"Everybody had to follow the same rules, whether they were students or farmers," said Mr Chainat. "We treated everyone equally, men or women. If any man was caught sexually harassing a woman, he would be killed.

"I took care of one case of that myself. We needed to be tough. Everyone had to respect each other. Otherwise, it would have been difficult for us to live together, given our members came from such diverse backgrounds."

He said that the Thai government tried to send spies to infiltrate the communist camp several times. "If the spies were caught, we would send them to be re-educated in a remote place. But if they brought forces to physically violate our base, we had to kill them," he said.

Mr Chainat learned to use all types of explosives and weapons provided by China. He met his former wife at the base and they had two children together.

During that time, the Thai government used a hardline approach to oppress communist activity. Defectors were prosecuted and killed.

However, according to Mr Chainat: "It was impossible to suppress us. When you got rid of one cell, more cells would pop up elsewhere."

The Thai government engaged in heavy battles with communist guerillas, but the former prime minister Prem later attempted to seek a truce.

On April 23, 1980, he announced Order 66/2523, outlining the key strategies in the fight against the communist insurgency. He sought to shift from a hardline stance to a moderate approach, applying social justice and amnesty to let defectors easily leave the insurgent movement.

"The government distributed leaflets throughout the communist-controlled red zones with the message '66/23 calling for communist insurgents to turn themselves in'," Mr Chainat recalled. "The government promised not to prosecute them and provide assistance to help them resettle in society."

Mr Chainat encouraged some to defect voluntarily. "After all the fighting, I'd seen so many killed and I feared I could not protect us any more," he said.

"But we soon changed our tactics from holding weapons to holding pens in our fight for equality."

Mr Chainat is one of 6,183 ex-comrades that the government will give a collective 1.4 billion baht of "pocket money" on Wednesday as compensation for defecting. These were promised by Prime Minister Prem to CPT members who left the party and joined the national development programme in 1980.

In the compensation programme, former CPT members were first given plots of land, followed by incremental monetary packages in 2002 and 2009. The last part of the plan is expected to be executed this week, says Col Phirawat Saengthong, spokesman for the Internal Security Operations Command.

According to Mr Chainat, the CPT initially sought out 15 rais of land in compensation, including sufficient space for a house and five cows for farming. However, the government couldn't meet such demands so they agreed on a settlement of 225,000 baht.

Mr Chainat now lives on a plantation in Korat with a small chicken farm. Of all Thailand's leaders, he said he respected Prem the most for his leadership and keeping his word with the CPT.

Manassaporn Sributr, a 53-year-old farmer from Udon Thani, is another ex-comrade who will receive a compensation package on Wednesday. She joined the CPT in 1977 without much knowledge of the communist cause. She joined the movement when her village was accused of being communist after protesting a dam construction plan in Ban Nong Bua Buan village in Nong Wua So district.

When Lhon Laowong, a community leader in Ms Manassaporn's village, was found dead in 1975 for unknown reasons, the villagers were left in fear. Then, one day, CPT members came to the village and persuaded them to join the cause. Ms Manassaporn was only 15 when she followed her parents to the jungle and was renamed Comrade Porn.

She stayed in the jungle for three years to do intelligence work and defected when she heard of Prem's new policy.

Today, Ms Manassaporn is the leader of a women's club in her community. She has returned to farming work and supplemented her income by selling Giffarine products.

Ms Manassaporn did not find it hard to adjust to life outside the jungle.

"Everyone was a communist here," she said with a laugh.

She said she still keeps close contact with her old comrades in other provinces. "Comradery is more than friendship. We really would have died for each other."

Taken out of sight: Students and activists retreated to the jungle to join the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) after the bloody pro-democracy demonstration in Bangkok on Oct 14, 1973.

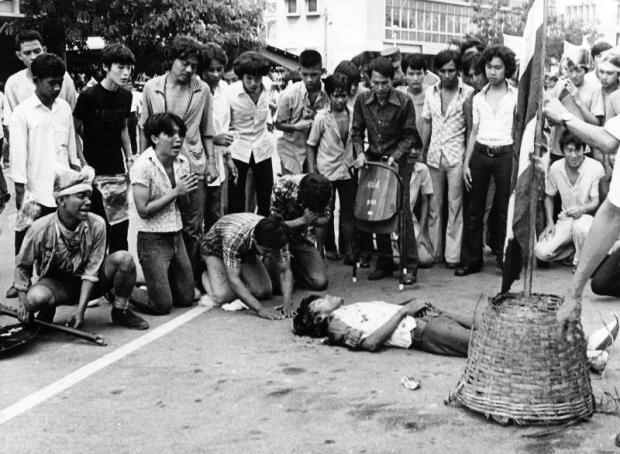

Activists down: Dozens of students died during the Oct 14, 1973 protest.