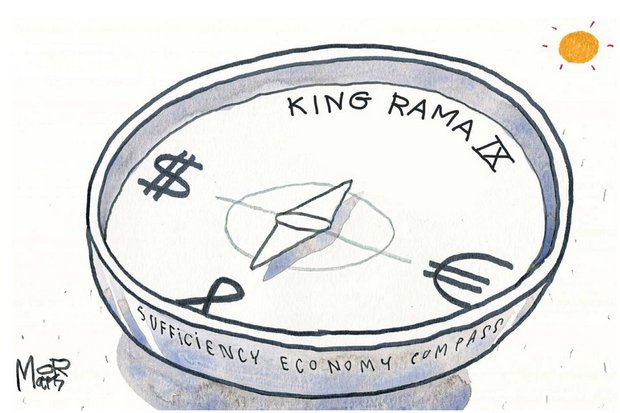

Since the passing of our beloved King last year, so many people have vowed to put his sufficiency economy theory into practice. While they are following the theory, it happens that few are aware of a core principle behind it -- that people should not take advantage of others.

While mainstream economics may not count "taking or not taking advantage of others," as a factor that affects the need to fulfil our satisfaction, there should be a rule or regulation for a society to prevent people from taking advantage or exploiting others.

But the sufficiency economy theory is different as it requires us to have the non-exploitation principle in our heart. This goes beyond rules or regulations. In following that principle, we have to examine and re-examine our relations with others to see if we are -- with intention or not -- exploiting or taking advantage of them.

Decharut Sukkumnoed is head of Kasetsart University's Agricultural and Resource Economics Department. He is well-known for his civic role.

Exploitation or taking advantage of others can occur in two ways, intentional and non-intentional. With regard to intentional exploitation, we have to use morality as a tool to control behaviour of people in society, preventing them from taking advantage of others or curbing such indecent behaviour.

But the second type of exploitation, the non-intentional or inadvertent one, is more difficult. It may occur sub-consciously and that may not be easy to identify. We need to train our thought to help us recognise such behaviour and avoid it. Inadvertent exploitation usually occurs in a society with disparity where people do not have equal access to natural resources. The disadvantaged tend to be exploited by those in a higher position. A prime example is people living in provinces or areas designated as water retention areas who have to make sacrifices to allow Bangkok, the capital, and a few surrounding spots to stay dry.

Other examples are a system that makes it not possible for farmers to get fair prices for their produce and where they have no other choices, or for labourers who are deprived of an opportunity to increase their income or welfare, and are stuck with low-paid work compared to bureaucrats and white-collar workers.

Inadvertent exploitation may also come in the form of us carelessly using fossil fuels that cause pollution and climate change. this takes place at the expense of people of the next generation which means we are taking advantage of people of a future generation. Therefore, it is evident that "happiness" -- a life that is free of flood, and a chance to enjoy inexpensive food and cheap labour (when compared to other countries) or careless use of energy -- is based on unequal relations or disparity that allows a chance for exploitation that we are not aware of. The problem is we tend to take this tacit exploitation as "normal," and hardly have hard feelings against it.

Making exploitation "normal" is a way to justify the unfair process as it stops people from seeing abnormality or raise a question against it. To make people collectively regard it as normal to exploit others requires socialisation process which can be formal, through education, or informal through proverbs or slogans. In particular, if such a process can make the less privileged accept exploitation (through the belief about destiny and fate, for example) or think that their being taken advantage of is normal, justification is completed.

But the late King's sufficiency economy theory requires us to be aware of our relations or interaction with others, not accepting normality with tacit unfairness. Yet we have to admit that exploitation can be systematic, and that makes it even more difficult for us to debunk it. But if we are aware of it, we can fix it in many ways. Firstly, we need to re-examine ourselves and our relations with others to see if there is exploitation which can sometimes be hard to recognise. This applies especially when it is systematic exploitation that comes out in our favour.

Secondly, if we know we are in a position to take advantage of others, such as gaining a bigger income than labourers (in my case, my salary is higher than those at the lower end of the social spectrum), we may compensate by doing social service. Simply put, if we gain a benefit from the system, we should sacrifice and serve others more. That may not be easy, given the fact that the value of our social work may not be equivalent the amount we earn. But that means we should make up by working even more to serve others.

Thirdly, we should always make it possible for others to exit the relationship with us. If people have choices, the chances for us to take advantage of them will be smaller.

Finally, we must advocate for fair distribution of natural resources and public good such as improvements in the welfare system or better education. We should support the principle of fair income, progressive land and property taxes as well fair land distribution. This would minimise systematic or inadvertent exploitation. We can say the late King's sufficiency economy theory involves a paradigm shift: from economics for natural resources management to fulfil our wants, to economics for managing our wants. It stresses the need to share more to ensure fair use of natural resources that helps us achieve sustainability.

This article is an adaptation of an article Mr Decharut wrote for his children, and was previously published on The Matter web page.