Much has been and more will be said of Dr Surin Pitsuwan's sudden and unexpected passing due to heart failure on Nov 30, at age 68, just when he appeared to be going from strength to strength after his stint in 2008-12 as Asean secretary-general. Many will also say that among the 13 heads of Asean in its 50-year history, Surin was the most effective and formidable. Indeed, he managed to speak for and champion Asean's causes and roles in Asia and the wider world even long after he left the job. No secretary-general of Asean is likely to come anywhere near the level of his eloquence, charm and charisma, the presence and confidence that his tall frame and good looks yielded. But Asean was second best for Surin. He was better than what he ended up with, unable to find professional landings commensurate with what he could bring to the job.

His rise to greatness is well-known. Surin was a native son opf Thailand from the southern province of Nakhon Si Thammarat, a Thai-Muslim from humble origins who climbed one ladder after another through brilliance and hard work. He eventually earned a PhD at Harvard at a time when American academia was not so interested in Southeast Asia after the United States had lost the war in South Vietnam. His dissertation on "Islam and Malay Nationalism" rings true today as an ethno-nationalist framework to analyse and accommodate the Malay-Muslim insurgency in Thailand's deep South. Later, Surin went on to a university career and a public intellectual role in journalism. And then he was repeatedly elected MP in his province, starting in 1986, always with the Democrats.

After junior cabinet roles, his political career reached its pinnacle when he became foreign minister in the Democrat Party-led government during 1998-2001. As someone who was attuned to think ing"outside the box," Surin came up with answers for Thailand and Asean that seem improbable. For instance, his "flexible engagement" to draw out and incentivise Myanmar's reclusive and brutal generals to open up and his instrumental role in the United Nations' intervention in East Timor were legendary. He proved as Thai foreign minister that he had so much more to offer.

Leading the United Nations was his unfulfilled calling. His profile as a moderate, internationalised Muslim and a Thai statesman with immense international stature and proven regional success rendered him the right fit for the job. Surin had the support and no objections from the major powers. But here is where Thai politics got in his way.

By 2004-2006, when the race to succeed UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan was in full swing, the Thai political landscape was under the purview of the Thaksin Shinawatra government, which forwarded its own candidate. Without full government backing, Surin had no hope of building support bases from Asean, developing countries and the bigger powers. His chances were doomed. In the end, South Korea's Ban Ki-moon got the role but many in the world of diplomacy and international affairs will likely maintain Surin would have been a far better choice. The UN secretary-general was his first-best job landing after becoming Thai foreign minister.

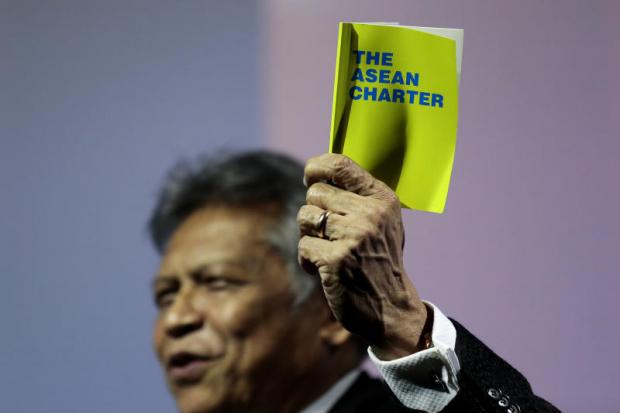

Around then, the five-year term of Asean Secretary-General Ong Keng Yong from Singapore was about to wind down. It thus became available as second-best for Surin, but he accepted and turned Asean into a regional player on the global stage, enabled by his intimate knowledge of the inner-workings of the 10-member organisation. His effectiveness as Asean chief is also well documented, particularly Myanmar's devastating Cyclone Nargis in 2008 when Surin's leadership adeptly skirted around Asean's cardinal "non-interference" principle and enticed the ruling generals in Yangon to allow international assistance. His efforts were always first rate even though the job ultimately was second best.

After leaving the secretary-general post, Surin was still in high demand for all things related to Asean. And he usually obliged all manners of requests for his role, whether speaking to young students or to older think-tank analysts. By then, he should have landed back in Thailand in a national leadership role. But the military coup in May 2014 kept him away on the Asean speaking circuit.

Some chided him for taking only a small part in street protests led by the People's Democratic Reform Committee that paved the way for the putsch. But the PDRC movement transpired in two stages. Before 9 Dec 2013, when new elections were called, the protests were legitimate as a social and spontaneous opposition to parliamentary manipulation that passed a blanket amnesty bill in the wee hours in cahoots with the the government of then-prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra. It was this first stage of the PDRC that Surin was more associated with.

In recent months, the Democrat Party that propelled his political career should have made space for Surin. Some asserted that predominantly Buddhist Thailand can never be led by a Muslim. But this is untrue because Gen Sonthi Boonyaratglin, a Thai Muslim, not only became army chief in 2005 but led the military coup in September 2006. In this country, an army chief can be more powerful than a prime minister, and the two offices can be held by the same person.

Thus Surin could and should have been the Democrat Party's leader. But the incumbent leadership that has lost elections repeatedly just won't make way. As he was a public service executive by training and preference, Surin had nowhere left to aim but the Bangkok governorship.

In our last conversation just two weeks before he permanently departed, I (like many of his friends) urged him not to run in the Bangkok governor's race. It is a poison chalice, a no-win and thankless task. The only Bangkok governor who did well and is remembered that way is Chamlong Srimuang from the 1980s. The rest became tainted in different ways. The former Asean secretary-general and also-ran UN secretary-general listened, as he always did, and suggested lunch for further discussion, just as he took to the stage to make yet another mesmerising Asean speech before a capacity crowd.

Surin offered a lot more than he delivered because he was not given bigger chances.

Thailand has been a sub-par country because it does not do justice to its best talents and minds. Few will be able to soar to global heights and local greatness that he reached. Among Surin's legacies is Thailand's need to cultivate and harness local talent and let them rise to their full potential.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak is associate professor and director of the Institute of Security and International Studies, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University.