Even before President-elect Joe Biden is officially anointed as the United States' president, a curse has already been cast on Thailand by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who on Dec 3 passed a resolution regarding the ongoing political unrest in the kingdom. Before spreading this false impression far and wide, the incoming Biden administration should pay full attention to the realities on the ground in Thailand, beyond political correctness reserved for a typical human right and democratic struggles. Otherwise, it could lead to unintended consequences on Thai-US relations as well as the US policy towards the region.

Thailand has to be prepared to engage the new US presidency for two main reasons. First, Mr Biden and his foreign and security teams understand "the big strategic picture" and the broad nature of US vested interests. Second, it has plans to pursue a policy of liberal internationalism, with an emphasis on human rights and democracy. Given the two distinct characteristics, the 202-year-long Thai-US relations looks set to once again face an enormous test.

Washington's perception of Thailand's geostrategic values in the wake of China's rise and the Covid-19 pandemic will determine whether the US's oldest friend in Asia will be a boon or a bane for itself. As such, Thailand must reach out to the Biden presidency and make use of its numerous strategic assets, as well as its time-tested diplomatic paybook, right from the start. From now on, it won't be "business as usual".

That said, here are Thailand's eight strategic values that the US should always keep in mind.

First, Thailand's political landscape has changed dramatically, from totalitarian to a "free and open society", following the people's uprisings in 1973. The transition was an imperfect one, chequered with violence and three coups in between, but for the past four decades, Thailand has been trying to become a functional, liberal democracy, as outlined by the Western definition of the term. While Thailand has failed to meet the grades required due to deep-rooted, unresolved issues involving key institutions and political traditions, we are still trying.

Despite the domestic idiosyncrasies, there is an increasing expectation that Thailand, given its past trajectory, should join the ranks of liberal democracies. As the domino that didn't fall when the region was gripped in turmoil, Thailand's democratic development was supposed to be the poster child for other developing countries in the region. To engage with the new US administration, Thailand has to bring back that image of a rules-based democratic country that respects human rights. Indeed, upon closer scrutiny, the Thai society, in general, is one of the most heavily regulated in Asean, as people tend to take the law into their own hands.

If the Biden administration ends up hosting the long-promised Summit of Global Democracy next year, Thailand must be included in the list of participants as part of the emerging liberal democracies group. Within the region, Thailand has come a long way since 1932, when it moved from absolute monarchy to a constitutional one. The rest is history, and it is now being played out on the streets of Bangkok and reported daily.

Second, Thailand is one of the five US allies in the Indo-Pacific region. After the end of Cold War, its strategic value receded dramatically, almost to the point of insignificance, due to the absence of common enemies. The evolution of the Thai-US alliance over the past decades was mainly focused on improving American troops' interoperability with its allies and friends, as well as maintaining the US military might in the region. That helps explain why the 38-year-old "Cobra Gold" drills, the Indo-Pacific's biggest annual military exercise has never been cancelled, even under military regimes, despite calls by both US and local lawmakers, as well as other stakeholders. Cobra Gold has now become a multilateral platform for America to influence allies and friends with its military doctrines.

The new administration needs to go beyond Cobra Gold and the procurement of military hardware. As a major non-Nato ally, Thailand is also considered the best "cooperative security location" for the US in the Indo-Pacific, as it can provide access, staging ground and training for its troops.

Furthermore, the Pentagon must renew its International Military Education and Training (Imet) programmes, which have been ignored for some time. Without Imet programmes, hundreds of young Thai soldiers have no opportunity to be exposed to democratic ideals and human rights. Over 10,000 Thai soldiers have been through the programmes since the 1960s.

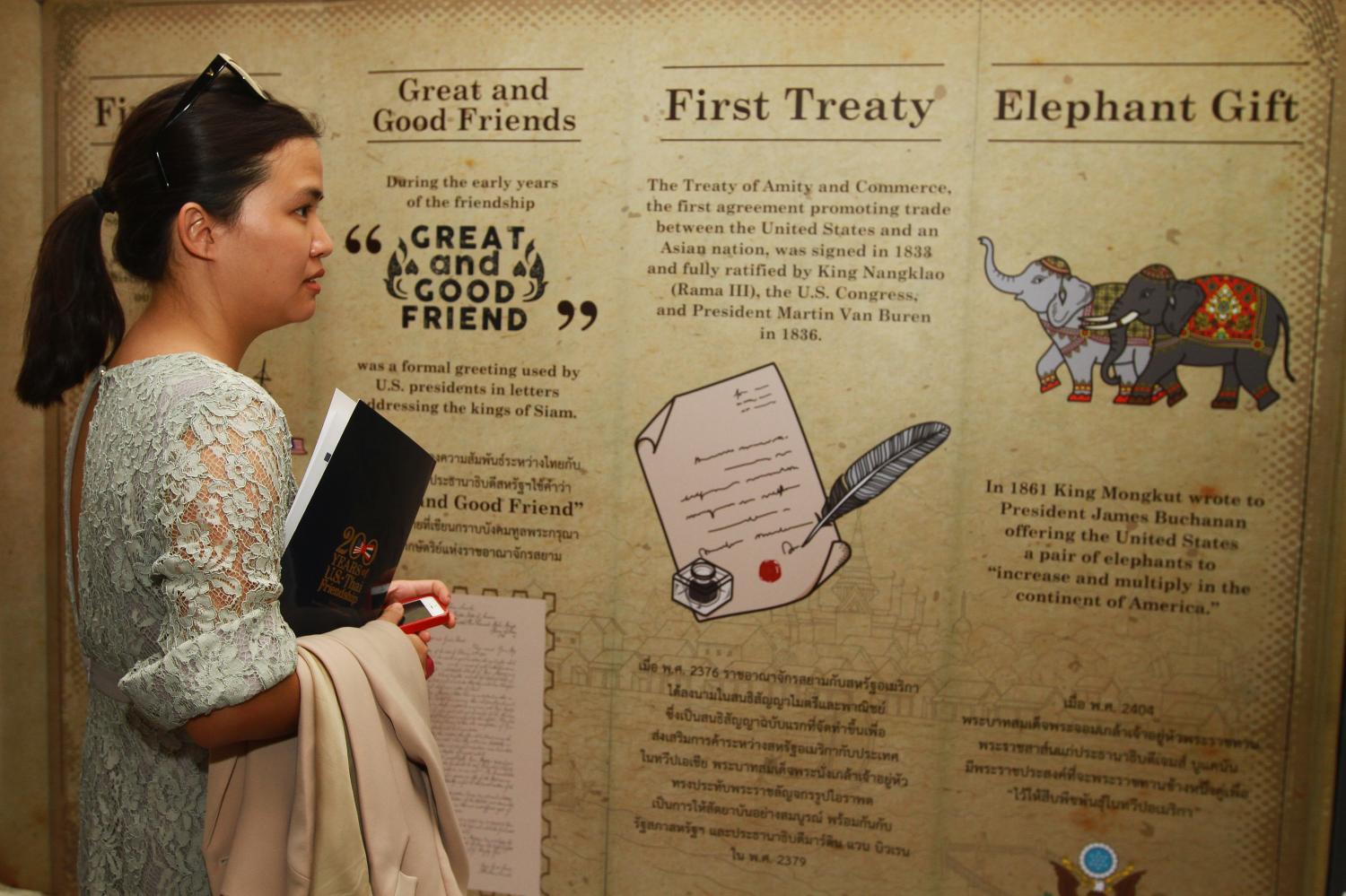

Third, Thailand is also an important trading partner of the US. Siam established ties with the US in 1818 and signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1833, granting privileges of trade and investment. The treaty was the first the US ever signed with an Asian country. No country in the region continues to grant privileges agreed two centuries ago to the US. Therefore, it is about time that Washington recognises this and looks for ways to diversify economic cooperation. Thailand is the US's 19th largest trading partner, with trade valued at US$40.81 billion (about 1.23 trillion baht) as of October this year.

Both sides should return to the negotiating table to complete the free trade pact that was aborted in early 2006, as new opportunities arise with mutual benefits for both. New areas of economic cooperation must be on the agenda including the manufacturing of electronic parts, logistics, connectivity infrastructure, food and health security, energy security and agricultural innovation. Thailand needs to import more from the US to reduce the burgeoning trade surplus.

Fourth, with 87 registered international non-governmental organisations based in Bangkok, Thailand is considered a major regional hub of multinational civil society organisations, especially those with headquarters in the US and Europe. Thailand has a high tolerance for foreign criticism, especially at this juncture, as long as the criticism and comments are fact-based. Leading foreign organisations such as the International Commission of Jurists, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and others have representatives in Thailand. They have kept the international community updated on the human rights situation in the country. Lest we forget, Thailand's local civil society organisations are one of the most active in the region, with over 24,600 registered and several thousand more unregistered entities.

Fifth, until 2006, the US State Department's annual report on the human rights situation around the world was the standard-bearer of the country's assessment of rights-related issues. That is no longer the case because the Thai National Commission for Human Rights has its own annual report, which contains more detailed and damning evaluations of cases and holds the government accountable. Local human rights defenders, such as Angkhana Neelaphaijit and Somchai Homla-or, to name but a few, are fearless when it comes to defending civil rights. Sad but true, the country's human rights records have been marred by 82 unresolved enforced disappearances since 1980.

Sixth, Thailand's press freedom used to rank very high within Southeast Asia. During the Chuan Leekpai government (1997-2000), international media monitoring organisations in the US and Europe ranked Thailand as a free press country. Since 2001 the level of press freedom has been backsliding and has yet to recover fully. For the past two decades, media freedom indexes released each year have seen Thailand occupy the lower quartile of the rankings, mainly due to political crisis prompted by coups. But of late, the proliferation of social media and bloggers have allowed for the expression of views once considered taboo. Today, all Thai media content providers, which are still lacking in professionalism, report in a way never before seen. At the international level, Thailand actively participates in the longstanding campaign for the safety of journalists and media impunity under the auspices of Unesco.

Seventh, Thailand is a good friend of China. Therefore, it is useful to the Biden administration, which has stressed the spirit of cooperation, rather than confrontation, in engaging with Beijing. Thailand can serve as a bridge-builder for the two superpowers, as we have no qualms about being an American ally while being close to China.

During the Cold War, Thailand managed to balance its ties -- without choosing sides -- with the big two powers without prejudice. Under its 20-year National Strategy, Thailand entertains no enemy, as such, it is in a good position to facilitate both powers' collaborative potential, especially common projects and activities that benefit regional peace and security as a whole.

Thailand must also recalibrate its US policy with clearer objectives. Bangkok must place maximum value on the alliance with the US, given the uncertain strategic environment and proliferation of non-traditional threats in the post-Covid-19 world. Of late, Thailand has been more assertive on issues related to international rule-based principles, both individually and under the Asean frameworks.

Eighth, in the era of the pandemic, Thailand is a great partner for health security. Thanks to more than three decades of US assistance in capacity building and research on contagious diseases, Thailand has developed a world-class healthcare system and capable human resources which have helped mitigate the horrible virus. Thailand is working with its Asean colleagues to ensure a speedy economic recovery.

All in all, these Thai eight strategic values should help the Biden administration set a clear pathway to deal with Thailand.

Kavi Chongkittavorn is veteran journalist on regional affairs.