The outrage committed by seven police at Nakhon Sawan Muang police station, in which they are accused of torturing and killing a drug suspect under their custody, would have disappeared unless a grisly video clip of the deed was exposed on social media.

The public would never have known, nor would legal action have been taken against this group of rogue policemen.

The case was exposed after "a junior police officer" sent CCTV footage capturing the scene to a well-known lawyer, who later released it on social media.

The footage shows Pol Col Thitisan Utthanaphon, superintendent of the station, covering a 24-year-old drug suspect's head with six layers of plastic bags, with his subordinates assisting him.

In the clip, which went viral, his subordinates grabbed the man's limbs and helped bring plastic bags, cloth and a water bowl -- apparatus used during so-called "interrogation".

After being suffocated by the bags, and enduring a beating, the suspect lost consciousness. The police tried to resuscitate him, without success. They reported to a local hospital that the suspect died of a drug overdose on Aug 5.

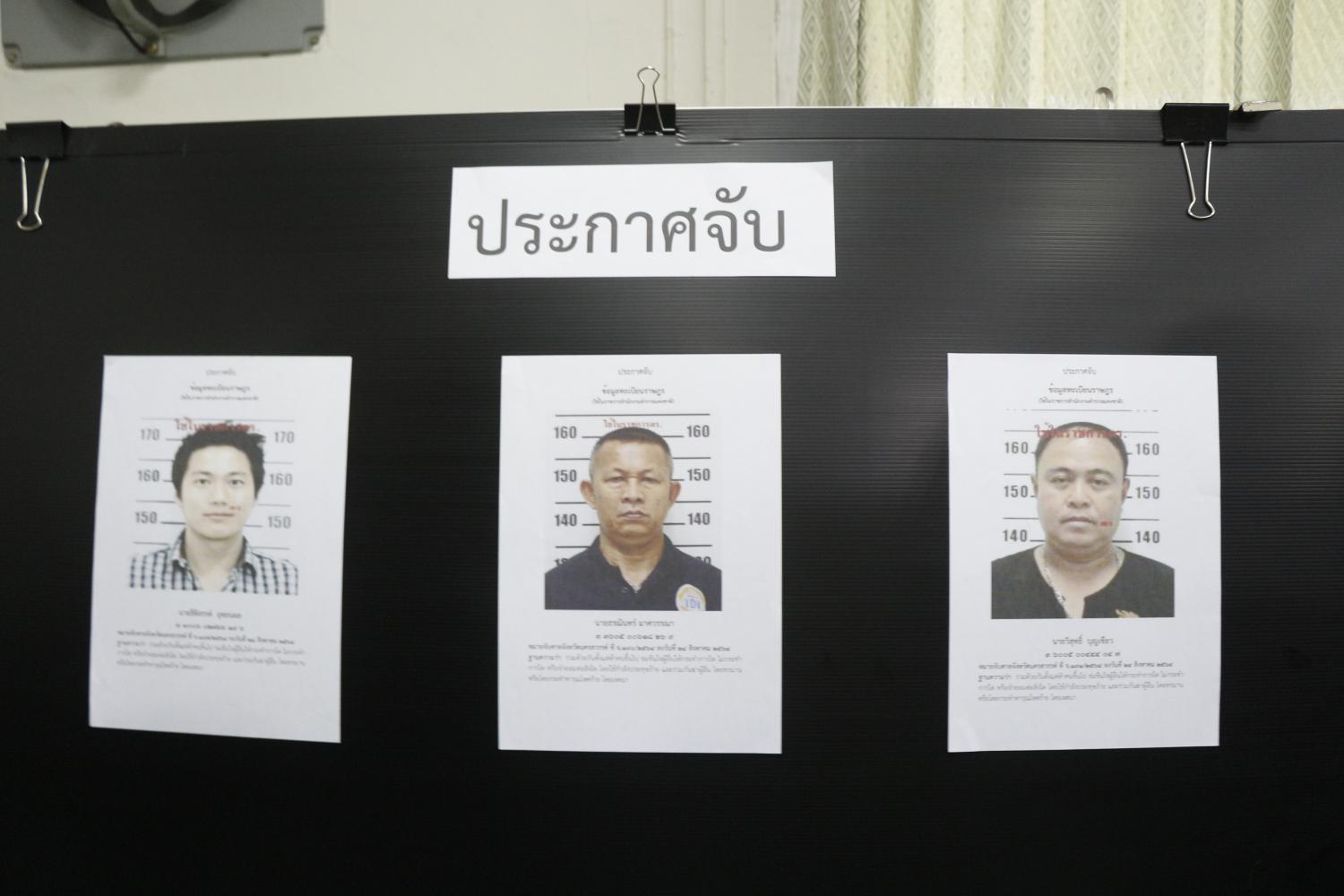

After the footage leaked last Tuesday, or more than two weeks since the man died, the Royal Thai Police (RTP) promptly arrested the seven police. Five were detained in Nakhon Sawan while the other two, including Pol Col Thitisan, first escaped but then turned themselves in on Thursday.

During a Thursday night press conference attended by a legion of media, the RTP chief allowed Pol Col Thitisan to speak to the media via a mobile phone held to a microphone. Pol Col Thitisan told reporters that he didn't intend to kill the suspect.

He justified his action by claiming he wanted to extract information from the suspect in his crusade to fight drugs. His subordinates helped him because he told them to.

The presser that people across the country watched turned into a backlash against the RTP. Critics said it was unfair to the family of the deceased who should have had a chance to defend himself in a trial.

But what struck me the most was the silence among the police. RTP top brass sat listening quietly as the suspect justified the use of torture as a means to fight drugs. No one spoke up to encourage whistle blowers, not to mention ensure their safety.

It has also troubled me to watch the footage. In the grisly nine-minute torture video, six subordinates docilely followed Pol Col Thitisan' directives without objection. They made the torture scene look like a chore, in which each ruefully lent his hand -- bringing in more plastic bags, strips of cloth or offering help to hold him down.

One of the six subordinates, Pol LCpl Pawikorn Khammarew, was quoted by his adoptive mother as telling reporters that he must strictly follow the former superintendent's orders.

"If you are there, there is nothing much you can do but follow orders," Pol LCpl Pawikorn was quoted as saying. His adoptive mother said if he refuised he would be punished.

A reporter's camera captured him wailing while being loaded onto a minivan taking him and the others from Nakhon Sawan station to a provincial prison.

Pol LCpl Pawikorn shouted to the camera, "Please give me justice." He comes from a farming family in the northeastern region, and also served as a driver for his boss.

From the police crackdown on democracy activists in Bangkok to the raid on innocent residents' houses in the deep south, police subordinates often act as docile accomplices. Some, like Pol LCpl Pawikorn, claimed they had no choice but to follow their superiors' orders.

This raises a big question mark. Can police subordinates resist their superiors' orders if it is against the principle of ethics and human rights? In other words, can they use their judgement to make the right choice?

In theory, I believe they can. But it practice, we know these subordinates are in a difficult position given the rules, culture and environment they are in.

The outdated Royal Thai Police Act, effective since 2004, underlines the hierarchy within the organisation and the power centralised in superiors' hands.

The law requires police subordinates to maintain discipline, including respecting higher-ranking officers and following orders "without resistance or avoidance". This opens a gap for unscrupulous superiors to abuse their power.

Of course, the Act also provides an avenue for police to launch a complaint with the RTP if the orders are illegal; the RTP then sets up a committee to investigate.

But this process will take time; the outcomes of such probes might also be less an ideal if the complaints involve police superiors with good connections and senior ranks.

Despite the RTP insisting the force is governed by a merit system and transparency, it is an open secret that nepotism and patronage underline the force's culture.

They also lay the groundwork of relationships among police and govern career path success.

This environment and culture fortify the RTP and its spirit of fraternity but discourage subordinates, especially those with no senior backup, to speak up.

So many police chose to conform, and those who do not find themselves in deep trouble.

In past years, media outlets have reported the suicide of subordinates who developed tension with superiors. Approximately 30 police committed suicide between 2013 and 2020, according to the RTP's Office of Human Resources website.

The culture of the force is like a cocoon -- a bubble unrelated to politics, society and people's sentiments in the world outside.

Many low-ranked police come from a humble background and look at a career in the police as a way to a better life, welfare and better social status.

For many like Pol LCpl Pawikorn, speaking up against their superiors means putting their career at risk, so they choose to go along and get along with their bosses, even when they are asked to break the law.

I don't mean to defend the six officers under Pol Col Thitisan. Some police can be good. But in a toxic system they can become corruptible, eventually.

These trends are why the RTP can seem to be a backward organisation. Without cleaning up the mindset and culture, police reform will be impossible, never mind promoting "new blood".

The RTP needs to learn from the crime committed by the seven police. It must reinvent its culture to prevent similar incidents in the future. Superiors will be less inclined to give such reckless orders if they know their subordinates can use their judgement without fearing the consequences.

Paritta Wangkiat is a Bangkok Post columnist.