I just ordered a set of children's books on Wednesday. No, they are not for my children, both of whom are grown-up, although the publisher says they are suitable for people between 5 and 112 years old.

The reason for the purchase was that I wanted to see with my own eyes what has caused all the hubbub about the books that were just recently released.

Who would have thought that a set of children's books could cause such an uproar in official circles that the deputy education minister would call for an investigation by a committee?

Is it a surprise? No, considering that the people involved in producing the books have a definite bent against the current system of governance and naturally attract hostile official scrutiny.

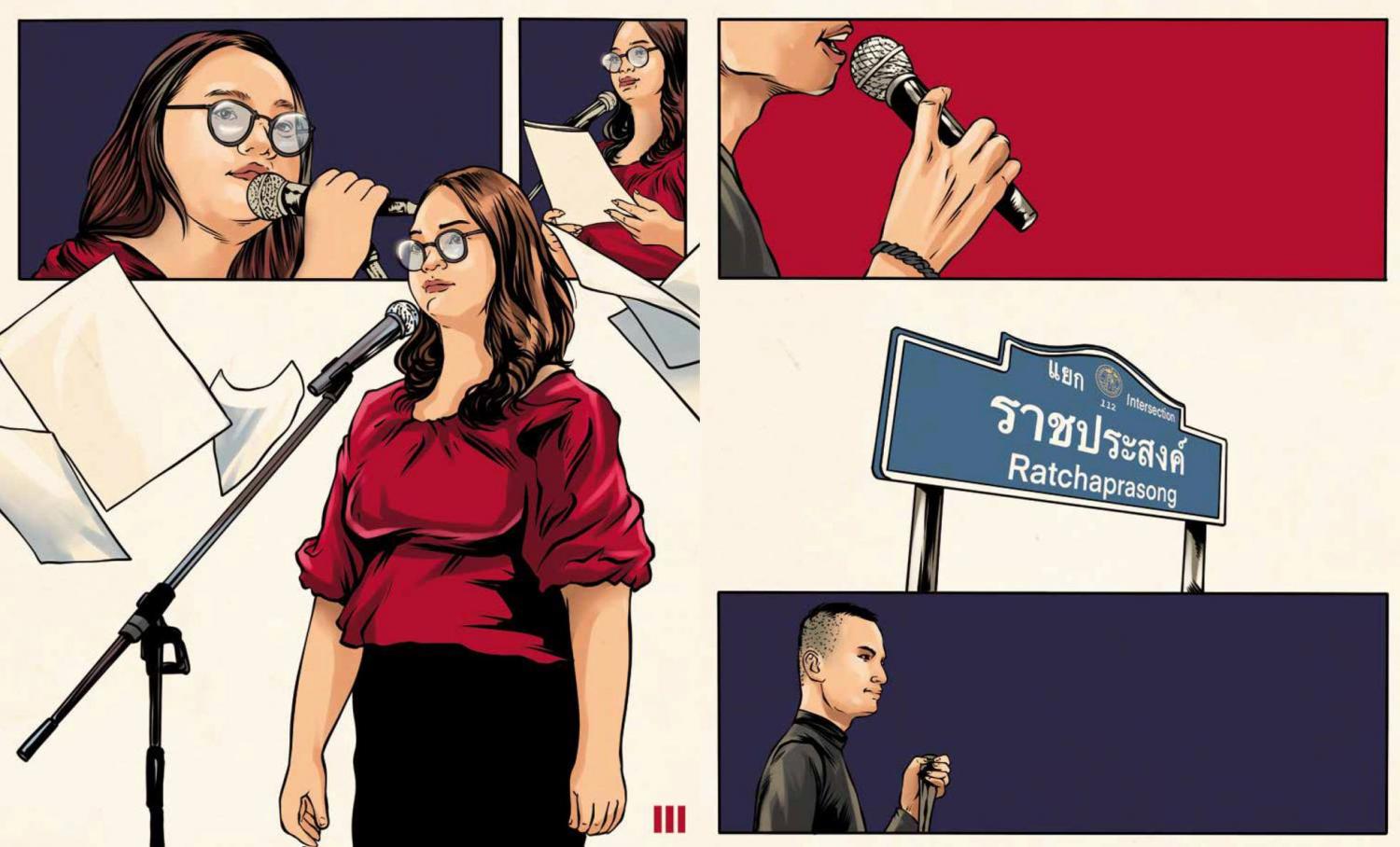

A pictorial image from '10 Ratsadorn', one of the eight books in the collection.

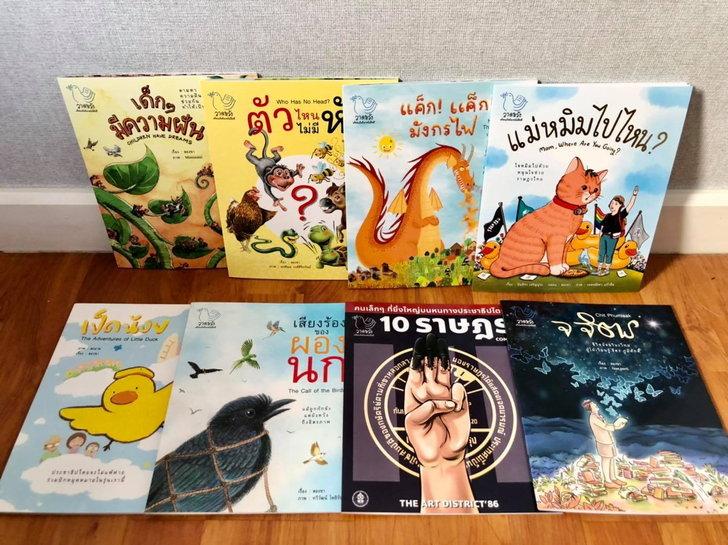

Promoted on the Facebook page Waad Wang Nang Sueu, the eight-book set "tells the dreams, hopes, diversity and dignity of children", says the publisher. "They also talk about cooperation, acceptance and creative co-existence."

However, Khunying Kalaya Sophonpanich, the deputy education minister, ordered an investigation after being informed that the publications contain misinformation that "could cause children misunderstanding if they lack correct advice from their teachers or guardians".

The investigators are tasked with finding out whether the books "incite hatred and impose dominating influence over the children since they are unable to distinguish between rights and wrongs".

Censorship, of course, is nothing new in Thailand, or under any totalitarian regime for that matter. Indeed, it is the most salient characteristic to distinguish a democracy from a dictatorship. A dictatorship simply does not tolerate dissent or different opinions.

Thailand has experienced censorship for much of its modern history dominated by military dictatorships.

During the regime of Field Marshall Sarit Thanarat more than six decades ago, newspaper publishers ran the risk of having their printing presses incapacitated if they published anything offensive to the dictator. A number of hard-headed journalists were locked up and some murdered.

Following the Oct 6, 1976, massacre of protesters at Thammasat University, surviving students hastily got rid of their collections of books considered to be anti-state, lest they be charged with communism and thrown in jail for an indefinite period.

Books or printed words in general are a weapon of necessity for dissidents in an authoritarian system. Thai dissidents have had a long history of expressing their sentiments and beliefs against oppressive regimes through printed words.

And the tradition of literary battle against dictatorial regimes carries on to this day. With the rise of the youth movement, new publications have been released, some of which have broken long-standing taboos, particularly involving the monarchy.

With the release of the new children's book set Waad Wang (roughly translated "Hope Imagined"), a new battle front has now opened. Most of the books are written by a well-known children's book author, supplemented by two contributors, both well-known activists in their own right.

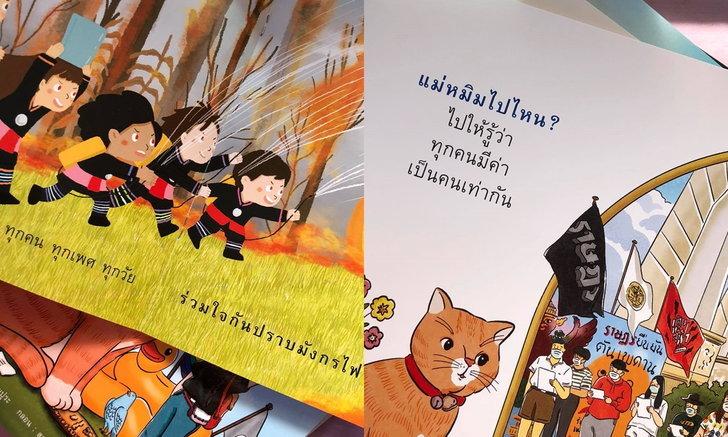

A pictorial image from 'Where is Mae Mim?', another book in the collection.

Children's books, particularly those approved as textbooks, always carry clear messages of state-prescribed moral and social values, leaving no room for children to form judgements and use their imagination. Even publishers of commercially-sold children's books dare not veer off the tradition for fear of offending parents.

These newly released books, however, are breaking new ground. Some in the set appear to carry clear political messages, something that is normally frowned upon.

But is it so abhorrent that children's books carry political messages? In Thailand's context, it is unthinkable, but not so in other societies.

In 1977, a publisher in Spain released a children book called Así es La Dictadura (in English "So This is a Dictatorship"). The following passage appears in the book (unofficial translation):

"The dictator is the law (because only he makes the laws). And so he is justice (only his friends can be judges).

"He also wants to command the army and education ... and factories, the field, offices ...

"He says that this is better. Because this way the neighbourhoods, the towns, the cities and the country are peaceful; because nobody complains and nobody protests."

The book was published a year after the death of Francisco Franco, the dictator who ruled Spain for 36 years.

This photo shows 'Waad Wang Nang Sueu', the children's book set produced by a publisher aligned with anti-junta protester groups, which is aimed at young readers. The Ministry of Education has questioned if the books are too political for elementary-level readers.

In a brief description, the publisher says of the book: "If we lived under a dictatorship, a book like this, which we might read with a smile, would never be possible. However, we must not get too comfortable: dictatorships are still a reality in many countries today, while others that claim to be democratic unashamedly recreate many characteristics of totalitarian governments…."

More than 40 years hence, dictatorships are still a reality. The ex-generals who rule Thailand today may try to fool the rest of the world that Thailand is a democracy. But those of us here know full well we live under a dictatorship, in content if not in form.

The book set Waad Wang will attempt to tell today's Thai children that there is an alternate system of governance where they can hope and dream for a better country and better future.