Early this month, a bright young colleague called me, telling a story about her difficulty in persuading a leading Thai research agency to explore how society could prepare policies to handle the prevalent problems of violence.

A scientist who is one of the research agency's chiefs told her and her team that we should not invest in this kind of project because Thai society is peaceful and violence has never been a problem for us.

Wondering which planet she was on, my colleague informed her that the idea of Thailand being a peaceful society is wrong and that violence has always been a major problem. The research chief's response was to leave the meeting room.

Using two cases of extreme violence that occurred on the same day, Oct 6, but 46 years apart as benchmarks, this article is an attempt to point out that violence has always been a problem in Thai society.

This does not mean that Thai society is more violent than others because one can point to many nonviolent and peaceful times in the past. What needs to be emphasised is that Thai society is ordinary in its propensity towards violence. But by squarely confronting such a reality, we might stand a chance of fostering ways to mitigate its effects.

I begin by affirming the fact that while these tragedies are cases of extreme violence, they are certainly not the same. Carefully identifying specific types of violence, might point us in the right direction as to how such violence could be alleviated. Finally, the crucial need to confront an "honest" portrait of Thai life will be briefly examined.

Tale of two tragedies

Oct 6, 1976, was a case of state violence committed against innocent citizens by various groups, some of which were part of the state apparatus, while others were not.

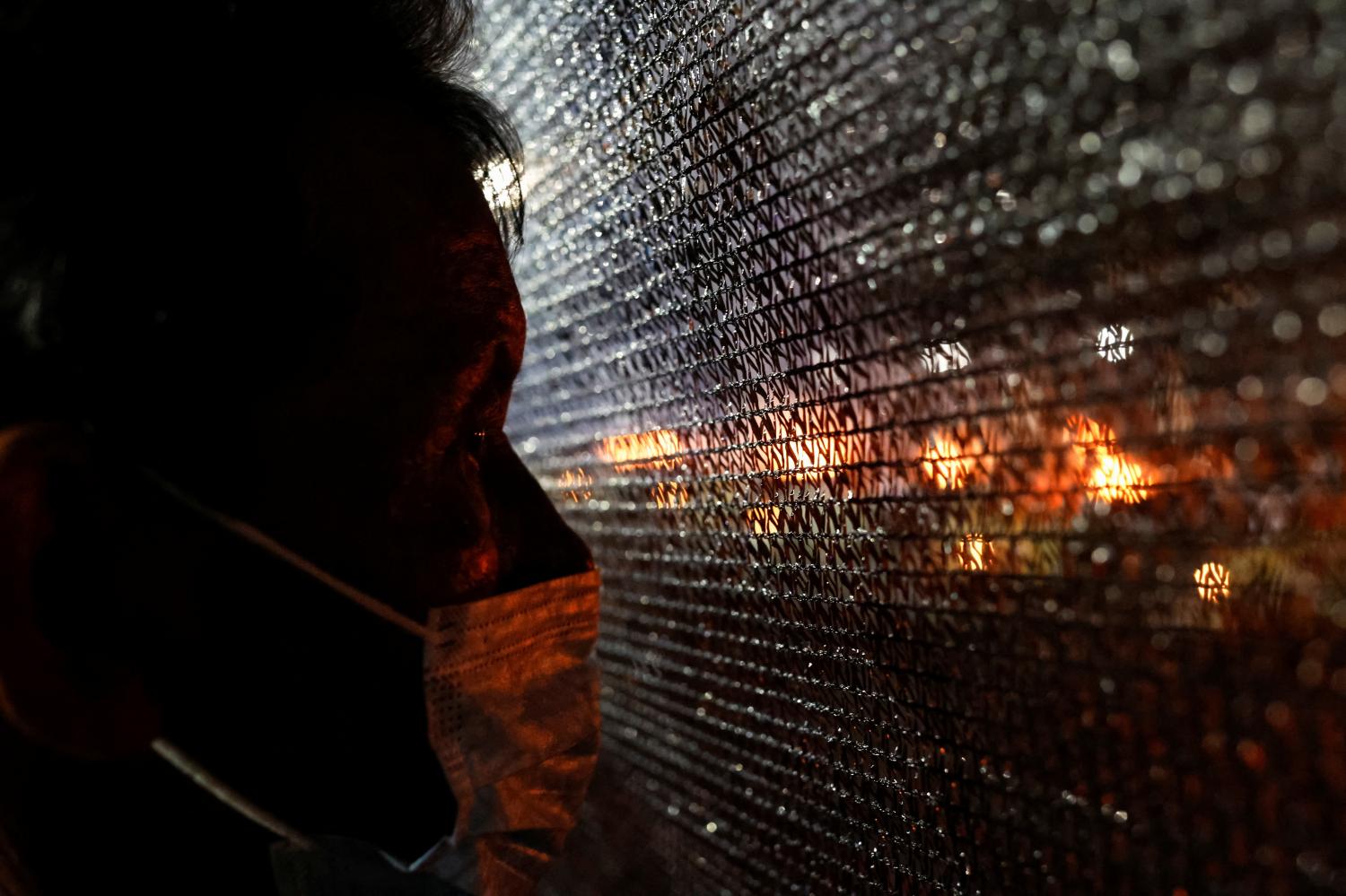

But most significantly, it was carried out with inexplicable brutality: burning humans alive, with mutilated dead bodies hanging from tamarind trees in Sanam Luang while people watched passively.

The lynchings were carried out from dawn, on what is arguably hallowed ground, not far from the revered temple of the Emerald Buddha.

It needs to be mentioned that the lynching was made possible after the students and protesters gathering at Thammasat University were repetitively demonised by the media, public and private.

Lessons from genocide studies such as Rwanda 1994 inform us that effective and repetitive demonisation of victims often precedes a pogrom.

The Oct 6, 2022 tragedy at Nong Bua Lam Phu was a case of a mass shooting, part of the epidemic of violence plaguing today's world. A year ago, Jillian Peterson and James Densley published the book The Violence Project: How to Stop a Mass Shooting Epidemic.

Their research constructed a database of every mass shooter since 1966 who had shot and killed four or more people in a public place, and every shooting incident at schools, workplaces and places of worship since 1999.

They also compiled detailed life histories of 180 shooters, speaking to their spouses, parents, siblings, childhood friends, colleagues, their teachers, and five surviving gunmen serving life sentences; most such killers did not survive the horror.

Here are some useful findings from their research.

- First, mass shootings/killings are socially contagious due to massive media attention.

- Second, these mass killers do have a "consistent pathway": early childhood trauma produced by violence at home, sexual assault, parental suicides, and extreme bullying.

These shooters grow up with inclinations towards hopelessness, despair, isolation, self-loathing, rejection from peers, and some had attempted suicide.

- Third, mass killings are often acts of violent suicide. These are simultaneously homicide and suicide because several killers design suicide as their final act.

- Fourth, "hardening school" security measures might not be a solution. After the Columbine Colorado mass shooting in 1999, American society shifted its focus to "hardening schools" (installing metal detectors, armed officers, and teaching kids to run and hide).

The Thai minister of interior is said to be keen on following in their footsteps. But this preventive measure does not work because over 90% of the time, school shooters are insiders. They target their own schools.

Killing children epidemic?

The Oct 6, 1976 tragedy followed a vicious demonisation project against the students who were defending democracy. By contrast, there was no demonisation in the violence last week.

The perpetrator used knives and guns to take the lives of 37 people including his wife, her child, and himself. Notably, the 22 preschool victims comprised 19 boys and three girls.

All were killed not by the killer's gun, but by his knife. While it is easy to point fingers at mental illness, one study shows violent men kill five times more children than perpetrators with mental illness.

In fact, from 2008 to 2017, a total of 205,153 children aged 0-14 years old died due to homicide.

Some 59% of child victims were males, while 20% were below five years of age, according to 2019 figures from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Children with disability were a preferable target, while some parents who took their children's lives were motivated by altruistic thoughts.

In 2016, the US had the highest rate of homicide with 3 per 100,000 population of children aged 0-17, while in Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Timor Leste are the three countries with the highest children homicide rate of 0.4-2.3 per 100,000 population, according to the World Health Organization's record last year.

The two tragedies -- that of 1976 and last week -- reflect different types of violence.

While what happened 46 years ago warns us that toxic hatred being produced in society can give rise to abominable horror, the violence at the daycare centre last week shows us the harsh reality that the purity of children's innocence is not protection against the violence of a killer.

The big question is -- how do the presence of reproduced hatred and the powerlessness of the innocent to deter violence help us see society for what it really is?

In the book Stripping Bare the Body by US educator and journalist Mark Danner, former president of Haiti Leslie Manigat was quoted saying the political violence in his country "strips bare the social body" and shows how society really works because it's like placing "a stethoscope to track the life beneath the skin".

So if one wants to understand his/her own society, to be aware of the roots of injustice, and the complex layers of violence, ordinarily concealed in the imagined mythical version of that society, such violent tragedies as the October 6, 1976 and 2022 needs to be confronted, each distinctively remembered for what they truly were, so that we could together work to never again see such extreme violence ever appears to make this society broken with so many lives lost and futures stolen.