Accusing a politician of owning shares in a media company has become a convenient tool to get rid of a political enemy with little regard to the intention of the law.

The current legal crusade against Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit by those associated with the military regime is making all the headlines, but the Future Forward Party leader is not the only one being targeted. He and others are now fighting back.

Section 98 (3) of the 2018 Constitution and Section 42(3) of the MP election law prohibit an MP candidate from owning or holding shares in a media company.

The provision was first seen in the 2007 Constitution (Section 48) but it was limited then only to holders of political positions, not MPs or MP candidates.

No one disagrees with the idea of preventing politicians from controlling media outlets. The potential to manipulate opinion and slander rivals is obvious, but the intent of the law has been perverted beyond all reason in recent cases.

Nuclear option

It started before the March 24 election when Pubate Henlod, an MP candidate of the Future Forward Party (FFP) for Sakhon Nakhon, was disqualified for owning shares in a media company.

He brought the case to the Supreme Court for election cases after election officials disqualified him.

The officials had accused him of being a partner in Mars Engineering and Service Partnership Ltd. They claimed the business objective of the company is to operate radio, TV stations and newspapers.

Mr Pubate argued his company operated a non-residential construction business. The objective listed by the election officials was No.43 on a list showing the scope of businesses that his company “could” operate, he claimed.

It turned out Mr Pubate used the universal form widely used by tens of thousands of startups when registering a company. The form lists some 80 types of businesses a company can do. The reason the form is preferred is that the operator can change the type of business without having to register the changes with the Commerce Ministry later.

The Supreme Court for election cases ruled that since Mr Pubate had shares in a business with the objective of running newspapers and media, he could not apply to become an MP.

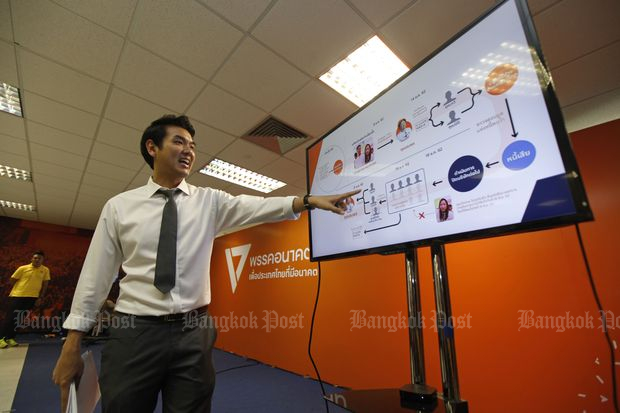

Now it is Mr Thanathorn’s turn in the spotlight. The Election Commission singled him out (again) this week after some media outlets reported that he still owned a media company when he applied to become an MP. He denied the accusation.

Mr Thanathorn held 675,000 shares in V-Luck Media Co Ltd, which published the people and lifestyle magazine Who! and an inflight magazine for Nok Air. The publications folded two years ago and the company was in the process of being closed pending some debt collection.

Mr Thanathorn claimed he had sold the shares to his mother on Jan 8 this year for 6.75 million baht. As evidence he showed the share transfer certificate signed by a notary, share certificates, an account-payee cheque and a shareholder register.

The change in the register of shareholders of V-Luck Media was reported to the Department of Business Development (DBD) at the Commerce Ministry on March 21.

The change in the shareholder register is simply an annual update that all companies have to submit to the DBD. For obvious reasons, the law does not require companies to inform the DBD every time a share transaction occurs.

Mr Thanathorn said that under the Civil Code (Section 1129), a share transfer takes effect when it is made in writing and with witnesses.

Some media outlets later challenged his claim, saying he was in Buri Ram on Jan 8 so he could not possibly have returned to Bangkok to transfer the shares on the same day. They floated the possibility that he had forged evidence to avoid being disqualified.

Mr Thanathorn will defend himself before the EC on Tuesday.

But if Mr Thanathorn is feeling persecuted, he can take solace in the fact that at least two junta-friendly politicians are in the crosshairs as well.

On Friday, the Pheu Thai Party submitted a petition to the EC accusing Charnvit Vipusiri of the Palang Pracharath Party (PPRP) of having 2.5 million shares in a media company and being its authorised signatory. Mr Charnvit was an unofficial winner in Bangkok’s Kannayao district while the Pheu Thai candidate came second.

And on Saturday, Apichit Tabutr, an FFP candidate for Sakhon Nakhon, asked the provincial EC to disqualify PPRP rival Somsak Sukprasert of the same constituency for having media shares. In this case, the company in question also used the standard form that shows a wide scope of businesses when registering the company, as in Mr Pubate’s case.

Mr Apichit said he submitted the petition because he wanted to see the same standard applied to all parties by independent organisations, citing what happened to Mr Pubate and the implications the case might have for Mr Thanathorn.

“If the EC and other agencies take action against Mr Thanathorn [for endorsing Mr Pubate], they must do the same to [PPRP leader] Uttama Savanayana since Mr Uttama also endorsed Mr Somsak,” he said.

Escalating risk

Having shares in a media company leads to disqualification if it is found before an election, but the candidate may run in the next election.

There is also the possibility that the disqualification of an MP could be used against his party’s leader if the latter has endorsed that person’s candidacy.

EC deputy secretary-general Sawaeng Boonmee said on Thursday that Mr Thanathorn, if disqualified, could face a criminal case for applying to become an MP knowing he was not qualified.

Moreover, since one of his MPs was disqualified, he could face further action for endorsing an unqualified candidate.

Some hard-core fans of the junta are even urging the EC to ignore all 6.2 million votes received by the third-ranked FFP in final MP seat calculations, as all of its MP candidates are tainted by virtue of their endorsement by Mr Thanathorn.

Meanwhile, critics have pointed out that a common-law wife of a stock tycoon who owns a large media group escaped scrutiny, simply because they did not register their marriage.

Blank bullet

The recent cases reflect overzealous and literal application of vague and poorly written laws with no attempt at common-sense interpretation, a chronic problem in Thailand.

As former prime minister Anand Panyarachun observed in a speech in 2016: “We must have rule of law rather than rule by law.” Thailand has always been an extreme example of the latter.

Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang, a lecturer at Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Law, wrote on Facebook this week: “Having laws but ignoring their intentions is like having a ship without a compass. Hyper-legalism is one of Thailand’s ills. It’s easy to tell. Laws are cited in doing everything yet justice and fairness have yet to be felt.

“Banning politicians from owning media was first seen in the 2007 charter. The writers then explained it was intended to enhance the rights and freedom of people to have access to independent media which are not dominated by anyone,” he wrote, citing Thaksin Shinawatra who was accused of dominating the media as an example.

Mr Khemthong questioned whether over the past 10 years the quality of Thai media has improved. “Do Thais have media that is straightforward and impartial? I suppose we know the answer.”

The provision is therefore not used as intended because the prime target has long since fled, and large media companies with political influence manage to evade it.

“The provision is therefore applied to bizarre cases such as companies which could operate media but in fact do not, or the owner of media which has ceased to exist,” he wrote.