Malaysia's criticism of Myanmar over the Rohingya issue has been vocal, especially in recent years. Government leaders have spoken out through different platforms, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

However, things have visibly changed in recent months, particularly following the Covid-19 pandemic. Kuala Lumpur has not only changed its tone but also its policy and actions toward the people it had stood up for. Its actions have indicated that Kuala Lumpur has transformed from being a vocal critic of violence against the Rohingya community to a country of refusal.

One important reason why Malaysia has been sympathetic to the cause of Rohingya is because of its shared beliefs in Islamic teachings. But it is intriguing as to why Malaysia has decided to change its perception toward the Rohingya whose fate is still very much precarious.

Of course, one widely reported reason is the fear of contracting Covid-19 through the refugee population.

Though it is not a signatory to the United Nations 1951 Refugee Convention, Malaysia has for years been one of the favourite destinations for Rohingya fleeing the oppression they are experiencing in Myanmar.

At the 34th Asean summit in Thailand last year, Malaysia strongly condemned violence against the Rohingya community. During a meeting with his Southeast Asian counterparts in Bangkok on June 22, Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Bin Abdullah called for the "perpetrators of the Rohingya issue to be brought to justice".

Earlier on Nov 13, 2018, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad slammed Myanmar and said, "It would seem that Aung San Suu Kyi is trying to defend what is indefensible… They are actually oppressing these people to the point of killing them, mass killing."

During an interview with Anadolu Agency in July 2019, Dr Mohamad had also said, "They [the Rohingya] should either be treated as nationals, or they should be given their territory to form their own state… massacre or genocide is involved and Malaysia is against genocide and the unfair treatment of the citizens of Myanmar."

In January 2017, former Malaysian prime minister, Najib Razak, called on Muslim countries to lead international action over the plight of the Rohingya. In his opening statement to the OIC gathering in Kuala Lumpur on Jan 19, 2017, Mr Razak said, "Far too many people have lost their lives in Myanmar. Many have suffered appalling deaths, and those that have lived through the atrocities have witnessed or endured unspeakable cruelty. That in itself is a reason why we cannot keep silent."

In a sharp contrast from its usual words of sympathy and concerns, Malaysian Defence Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob said on June 9, 2020 that boats carrying Rohingya refugees were not welcome in Malaysia and instead pushed them back to Bangladesh. The minister warned that "The Rohingya should know, if they come here, they cannot stay."

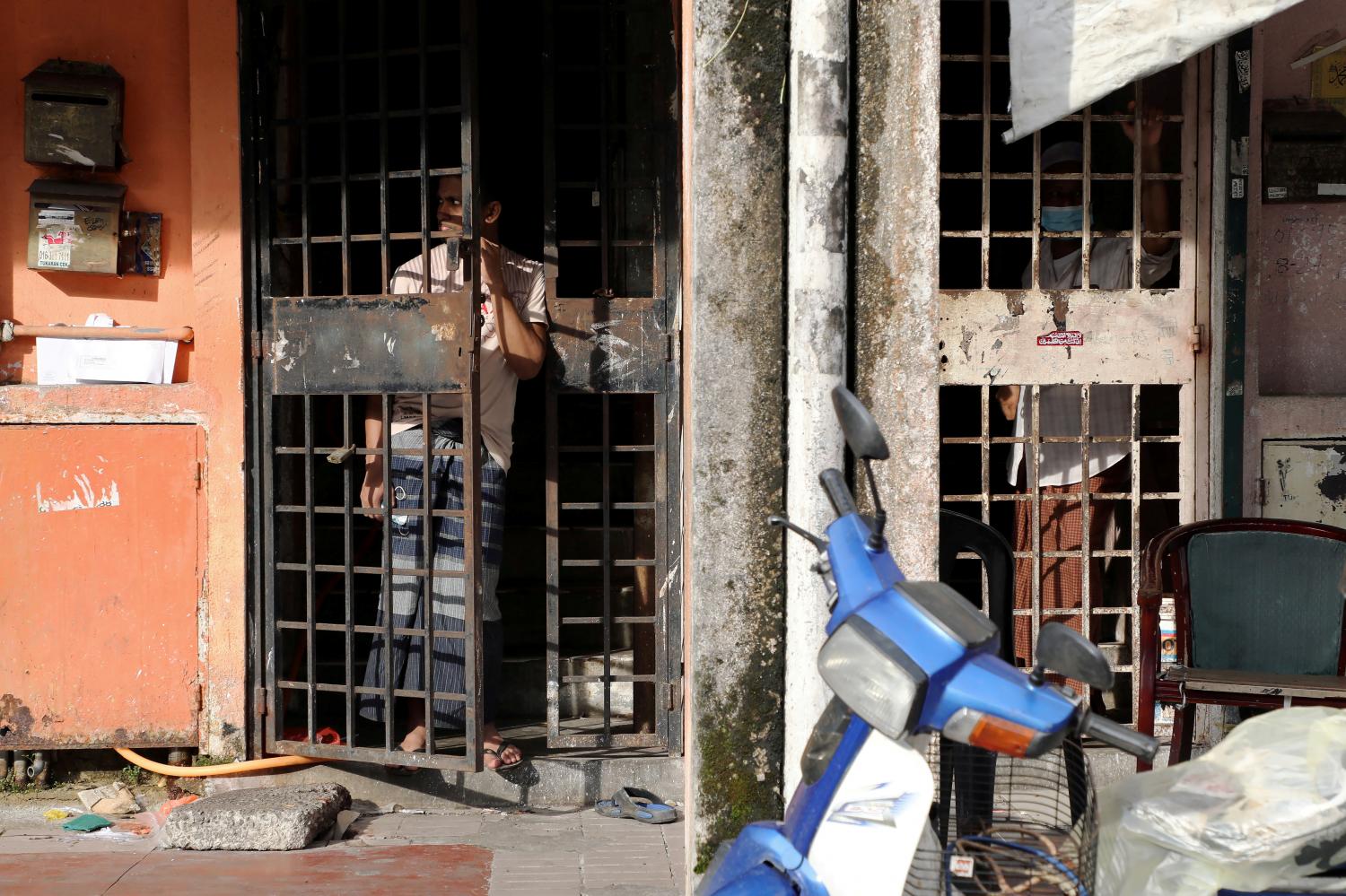

In early June this year, the National Task Force of Malaysia said it had detained 396 people attempting to sneak into the country illegally since May, along with 108 boat skippers and 11 suspected smugglers. During the same period, it had also turned away 22 boats with some 140 immigrants trying to enter the country illegally.

Not only is it refusing to accept the boat people, but Malaysia's tone has changed with heightened hate speech and xenophobic treatment in recent months.

The surge in hate speech is believed to have been triggered partly by claims that the Rohingya were demanding citizenship and other legal rights in Malaysia. The Malaysian government's decision in early April to turn back boats carrying Rohingya refugees also contributed to the increase in hate speech.

The rise in hate speech was followed by an anti-Rohingya banner in front of a mosque in the state of Johor which read "We are not welcoming Rohingya... We do not need you here."

On May 11, an open letter signed by 83 organisations, urged the government to combat online hate speech and xenophobia. The letter said, "We urge you to act immediately to address the recent proliferation of 'hate speech' and violent threats against the Rohingya community and to ensure the incendiary rhetoric does not trigger discriminatory acts or physical attacks." However, the letter seemed to have made no significant difference.

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to an increase in xenophobia against Rohingya. Recent incidents of refugee boat turn-backs and immigration raids of undocumented migrants have become an increasing concern since many of them live without legal protection in a society where they are often viewed with suspicion.

Moreover, due to the movement control order amid the Covid-19 pandemic, public health concerns have become an excuse to stop saving lives at sea and to display political muscle on immigration control.

Hence, Muslim-majority Malaysia which initially welcomed the Rohingya, has in recent months, hardened its rhetoric and dismissed the displaced people as illegal immigrants.

While Malaysia knows its national interests and security best, it can still show magnanimity in responding to the refugee crisis.

The failure of Asean to respond to the influx of refugees and provide a basic human rights framework has now demonstrated the failure of every Asean government in its unified vision of a "one Asean community".

Nehginpao Kipgen, PhD, is a political scientist, associate professor, assistant dean and executive director at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Jindal School of International Affairs, OP Jindal Global University. Diksha Shandilya is a Research Intern at CSEAS.